Topography and the Evolution of Bozeman’s Sewerage, Part II

This article tells the story of the second phase of the City of Bozeman’s sewerage development. Part one was published in the February 2015 Bozeman Magazine.

As noted in Part I of this article, of the many tax-payer funded public works projects built by the City of Bozeman, none is more integral to protecting the public’s health, safety and welfare than the sanitary sewer system. Since 1901, the City has utilized natural topography and scientific advances to deal with the City’s wastewater, preserve the community’s health and environment and meet environmental permitting standards.

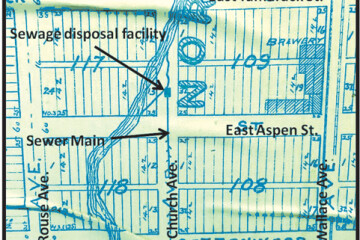

In keeping with Progressive Era politics, Bozeman’s voters approved $300,000 in bonds for public works projects in 1916. This included $70,000 to abandon the City’s current wastewater treatment site on East Aspen Street and Bozeman creek and construct a new facility three quarters of a mile north.

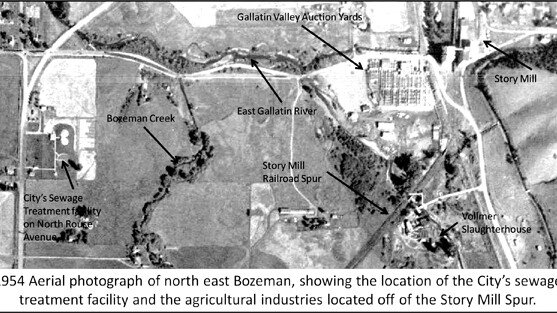

Located in the area of North Rouse Avenue and Griffin Drive, the new facility connected to the City’s sewage collection system with a 20” diameter pipe. The pipe emptied into two lagoons where solids settled from liquids before the liquids emptied into the East Gallatin River to the north. This treatment plant met the requirements of the State Board of Health, which initially prompted Bozeman quit dumping raw sewage into Bozeman Creek in 1907.

The new location was also over 50 feet lower in elevation than the old facility, which enabled continued use of gravity to move waste matter from source to treatment. Bozeman slopes gently from south to north, providing a natural terrain for delivery of water and removal of waste, with no need for mechanical pumping to the treatment facility. Development in the Imes Addition on the north side of town, between Peach and Oak Streets, was stymied between 1901 and 1917 because the subdivision lay almost parallel to the existing treatment facility on Aspen Street. Prior to construction of the new facility in 1917, there wasn’t enough downward slope to move waste to the treatment site.

Two industrial facilities developed near the sewage treatment plant in the 1930’s speak to the cultural acceptance of using creeks and rivers to dispose of waste matter. The Gallatin Valley Auction Yards provided corrals and pens for hundreds of cattle. Waste matter easily found its way downhill and into Rocky Creek. Joseph Vollmer constructed the Vollmer and Sons slaughterhouse adjacent to Rocky Creek, which provided ready disposal of the operation’s waste blood.

Public support for legislation protecting water quality regained attention at the end of World War II. A widely published report estimated that 2.5 billion tons of raw sewage entered streams, lakes, rivers and creeks every day. This prompted the Surgeon General to warn that over half of the US population relied on drinking water supplies of doubtful purity. The resulting Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 gave individual states the most responsibility for abating water pollution. Notably, the law failed to set scientific standards for water purity or to prohibit polluting activities.

A 1968 report on Bozeman’s public works facilities noted that the City responded to the increased scrutiny on water quality by passing $300,000 in municipal bonds to improve the treatment facility. “The improvements that were made in 1948 included primary settling tanks, digesters to treat the sludge and sludge drying beds. These improvements were designed to serve a population of 15,800.”

The 1940 US Census numerated Bozeman’s population as 8,665 people.

The City struggled to install new sewer line in pace with development during the 1950’s. Two problems arose: the inadequate capacity in existing sewer pipes to meet the demand of new development uphill and the need to install sewer pipe to service new subdivisions.

The pipe capacity issue was especially acute in the vicinity of Montana State College. The construction of Langford Hall dormitory in 1953 brought the issue to the forefront for the first time. The City eventually required MSC to construct a longer connection to the eight inch main at College and 9th Avenue, which could service a larger capacity. The issue arose again in 1956 and 1958, and resolved in 1963 when MSC agreed to partially fund construction of a major sewer line to service the campus in conjunction with the construction of North and South Hedges dormitories.

Two new subdivisions on the periphery of Bozeman challenged the City’s ability to extend sewer pipes at the end of the 1950’s. Bozeman Deaconess Hospital platted the New Hyalite View subdivision on the bench to the south and east of Sunset Hills Cemetery into the City of Bozeman in June of 1959. Rather than pump sewage over the crown of the hill near Highland Boulevard and into main on South Church Avenue, at the developer’s request the City enacted Special Improvement District 414, which assessed a fee to each property in the subdivision in order to fund construction of a sewage oxidation pond downhill in a ravine to the east.

Platted in May of 1960, the Westridge subdivision south of Kagy Boulevard and east of South 3rd Avenue faced a similar issue. Westridge was located nearly a mile from the nearest existing sewer pipe, which was woefully undersized to handle the additional load. In October 1962 the City accepted nearly $19,000 in grant funding from the Public Health Service to subsidize the cost of construction of an outfall sewer to serve Westridge subdivision. As a condition of the federal grant, the City made assurances to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service that the outfall effluent would satisfy current regulations.

Bozeman’s population passed 13,000 people by 1960, which again brought the issue of capacity at the treatment plant to the forefront. TDH Engineering of Bozeman submitted a consultant report in October 1967 which evaluated the City’s options in planning for the next phase of sewerage development. The report noted that Bozeman’s population increased about 25% every decade since 1930, and suggested the City consider their next investment as useful for a 30 year design period, or a population of 32,600.

TDH Engineering assessed the operational efficiency of the existing plant on North Rouse Avenue. “The existing primary sewage treatment plant is now operating at maximum capacity and would require extensive expansion to meet requirements for primary treatment. Montana law now requires secondary treatment which means that major additions and modifications are also needed to provide this further degree of treatment…In many instances the existing structures are in need of repair and the mechanical equipment is 20 years old and in need of major overhaul.” TDH estimated the cost of retrofitting the existing plant to be $776,000.

The plant’s location on North Rouse Avenue also posed a problem. “In recent years the center of population of the City of Bozeman has been shifting to the West,” noted the report. “Gravity sewer lines cannot be extended from the existing plant site to many of the anticipated areas of growth. Lift stations would be required to serve these areas.”

TDH evaluated the long-term cost of construction and maintenance of lift stations, and found it more economically advantageous to construct a new sewage treatment plant downstream on the East Gallatin River. “This site is ideal to serve the growth potential not only during the next 30 years but for many years beyond the design period,” concluded the report.

Federal grant funds provided up to 40% of the cost of construction of new sewage treatment plants. With this grant, TDH estimated the cost of new plant construction and related sewer main relocation and expansion as $1,167,000, which could be funded through public bond sales.

The City Commissioners voted to relocate the sewage treatment plant to new property on Springhill road in 1968. TDH prepared design documents for a new plant the same year. Later reports note that, “When bids were opened in 1969, they exceeded the available funds and the City, with concurrence from the State Department of Health, elected to construct the complete primary plant and equipment for approximately half the second plant... The plant was not constructed with the capacity to provide the total desired level of secondary treatment, but was constructed to provide a first step toward secondary treatment to be followed by additional facilities at a future date.”

The 1972 Clean Water Act pushed the City towards full construction of the facility. The CWA required permits for pollution sources while also providing up to 75% funding for improvements to municipal sewage systems. The City of Bozeman leveraged this grant source to complete the Springhill road treatment facility and construct a sewer main up the ravine to the New Hyalite View Subdivision lagoon. The facility’s outline can still be seen in the topsoil in aerial photographs of the area. A sewage main along South Third Avenue similarly connected the Westridge and Figgins subdivisions to the City’s system.

The Springhill Road wastewater treatment facility met TDH’s service goal of 30 years or a population of 32,600 people. The facility was significantly expanded in 2008-2009 at a cost of over $53 million dollars and uses the best available technology to create the cleanest effluent possible.

With sufficient capacity at the treatment plant, the City of Bozeman again faces the issue of pipe capacity to move waste through town to the facility. Sewage mains near Montana State University are again nearing capacity in the wake of growth of the MSU campus.

Topography also plays a role as Bozeman continues to grow to the west. Land west of Cottonwood Road has insufficient downhill slope to use gravity to move waste from the source to the treatment facility. Lift stations to drop waste into a higher sewage drainage basin will be necessary, which burdens development with the initial cost of construction and ongoing maintenance cost.