An Interview with Montana Raptor Center

Healing for the Hawk

Becky opened the wood door, unlocking the clasp without saying a word.

We stepped into the enclosure, a large, looming bird swooping above our heads to land on the other side of the room.

I let out a surprised, undefinable squawk, unsure if I should try and run, or remain stalk still.

Becky just laughed. “That’s Rosa for you,” she gestured to the hulking bald eagle in the corner, her head cocked in anticipation. “I don’t have anything for you,” Becky says to the bird, hands spread to show her she didn’t carry any food.

My interaction with Rosa the bald eagle was only the start of an enlightening day at Montana Raptor Center.

Passionate Care

Becky Kean didn’t set out to become director of rehabilitation at Montana Raptor Center. She began as a volunteer in 2003 after a professor at MSU mentioned the Center needed volunteers. “You start by doing all the fun stuff- cleaning cages, preparing meat,” she laughed. But she stayed on all the same, growing close to the birds along the way.

Founded in 1988, Montana Raptor Center cares for and rehabilitates injured raptors. Raptors are birds of prey, meaning the Center rehabilitates hawks, eagles, falcons, and owls.

Walking about the Center’s property, one starts to get a sense of how much Montana Raptor Center does on a day-to-day basis, with only 3 paid employees and 25 volunteers. Situated on a sprawling 12-acre property, with a beautiful view of the mountains, the Center has cared for 167 injured raptors this year alone. Most raptors are rehabbed and released back into the wild, with 14 raptors staying on the property as permanent residents.

All Begins with a Phone Call

You may be asking yourself, as I did, “How do you rehab a raptor?”

It all starts with a phone call.

“With the rehab process, it all starts with the people who find the birds,” Kean says. “They’re the heroes in the business. If they don’t report or bring the birds, we can’t do anything. So it starts with the people out in the field and knowing who to call.”

Injured raptors are often spotted by either drivers or property owners. “A lot of the time, property owners will just find them on the property…a lot of our admissions are also raptors hit by vehicles, so they may be next to the road still, stunned,” Kean says.

Often, a quick Google search leads individuals to Montana Raptor Center’s Facebook page, where they can contact Becky or others about the injured raptor. From there, the Center will talk you through what to do. One of the most important things to do is mark the area where the injured raptor is. “We suggest you mark the area, because a lot of times an animal’s camouflage is so good when we get there, we can’t find them,” Kean says. “Even just knowing we’re in the right vicinity helps a lot.”

From there, the Center employees figure out how they’ll get to the injured bird’s location. As the Montana Raptor Center covers the land between Dillon and the North Dakota border, getting a bird to Bozeman can often be challenging. The Center relies on a network of individuals, spanning across the state, to drive and hold the birds until they can reach them.

“Through the years, the center has established drop off areas, so if we can get a bird so far, say, to Miles City, I have a lady there who will hold them for us ‘til we get better transportation,” Kean explains. “So it’s kind of a leapfrog to get them all the way here…it just cuts our driving time down, as we’re a small staff, we can’t be everywhere at once.”

The Center often relies on its Facebook page to get birds closer to Bozeman. “Sometimes I’ll throw things up on Facebook, if someone’s travelling this direction, if they wouldn’t mind toting a bird along with them,” says Kean. “Mainly for those guys, it’s just a quiet taxi ride, the closest to Bozeman they can get.”

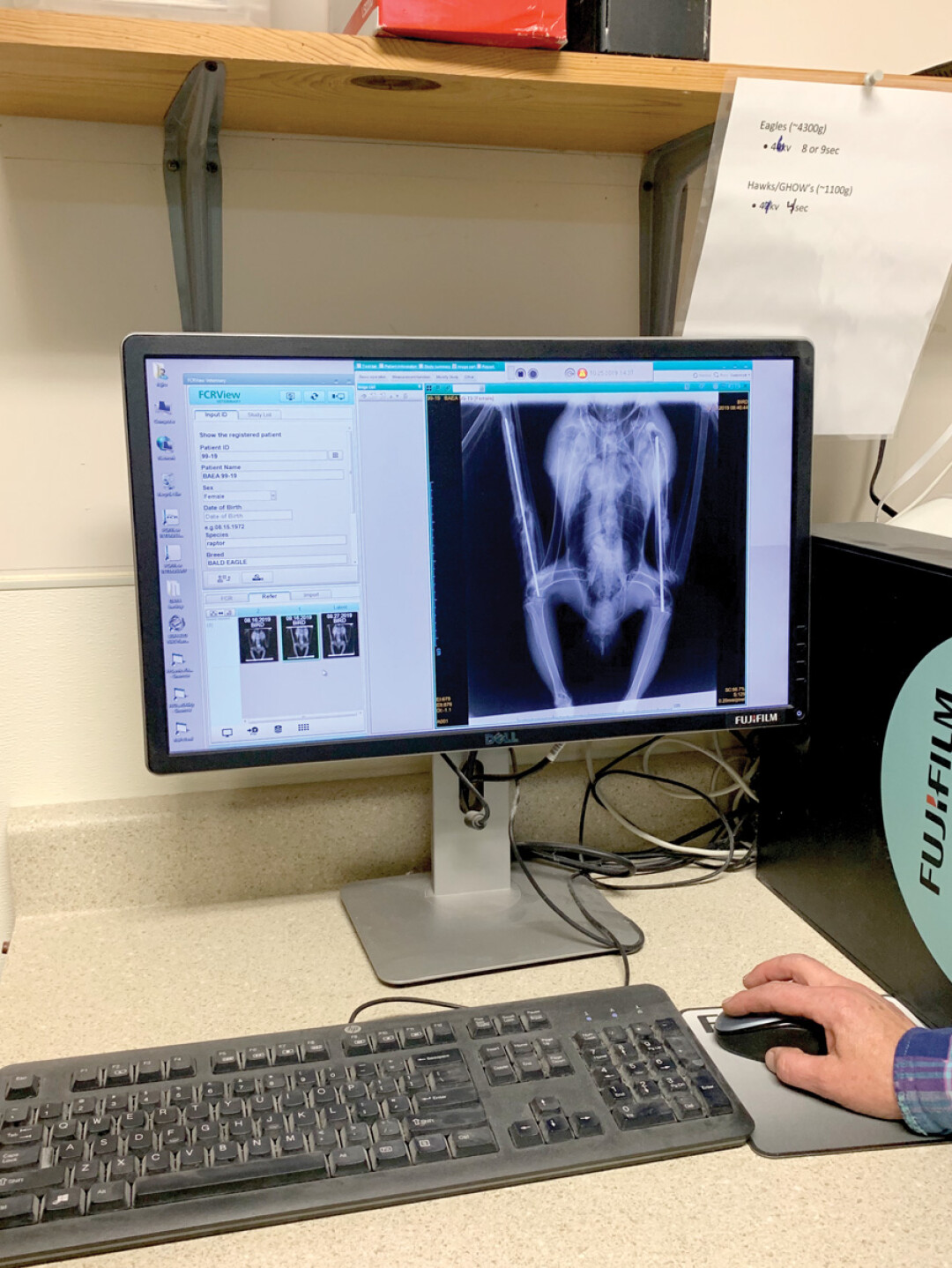

Once the bird finally reaches the Center, workers attempt to stabilize the raptor and call the vet. The Center works with a volunteer vet who donates her time and facilities while the Center buys supplies.

Stabilizing and rehabbing a raptor, once they determine what’s wrong, isn’t textbook. “It’s all kind of hands-on learning. We follow protocol for stabilizing any injury that we see.”

Kean gives an example of a common medical problem at the Center: dehydrated or starving birds. “For emaciated birds, you don’t throw a ton of calories at them because their systems could crash trying to metabolize all the calories you just gave them, ‘cuz they’re starving to death and their body’s pretty much feasting off themselves.”

As Becky explains the rehab process, we stop by each cage to look at the raptors recovering from their injuries. I was starting to get a sense of how much Becky cared about the birds. Every cage we stopped at, she could tell me how they were injured, how long they had been there, and what staff and volunteers had been doing to help them. We looked in at a short ear owl with a fracture in her left wing. A young bald eagle hit in West Yellowstone, unable to stand and a fractured wing. A pair of red tail hawks, their calls piercing, both hit by cars on the Interstate.

Ultimately, while the Center and the vet do as much as they can for the birds, as Becky puts it, “Not everything’s made to be in a cage.”

She looks at the raptors, their eyes watching us carefully from the cages. “We do a lot of keeping our fingers crossed around here.”

Human Problems, Human Solutions

Many of the raptors that come into the Center have been injured by humans, often with cars. But another mark of human interference on these birds, one I didn’t think of before I came into the Center, is imprinting.

Imprinting, as defined by PBS, is “…a critical period of time early in an animal’s life when it forms attachments and develops a concept of its own identity.” Birds are genetically programmed to imprint to their mothers. But when humans take birds out of their natural environment when they’re young, a bird will often imprint upon the human, with disastrous results.

Several of the Center’s raptors must live there permanently because they imprinted on a human. Many people, when they find a baby raptor, will take the bird into their home and raise it as a pet. While their intentions may not be cruel, it is devastating for bird’s development.

Such is the case for Stella, an American kestrel and permanent resident at the Center.

“Being an imprint, she can adjust to captivity a lot easier, because they think they’re one of us,” Kean explains. “That’s why she’s not scared. People raised her as a young baby. And that’s why we could never release her. In the wild, she has no idea of other predators, she’d become someone’s meal very quickly, and if she’s hungry enough, she’d fly to your lap for food, cuz ‘people fed me’ and she’ll think you’re her mom.”

The same goes for Rosa, the bald eagle I was woefully unprepared to meet. As a baby, people noticed they could get very close to Rosa without her moving. The Center discovered she’d been made a pet- and thus imprinted on humans. Nothing is physically wrong with her, but she can’t survive in the wild. “She’ll start begging for food at the picnic table,” Kean says. Looking at the majestic bird staring us down in the corner, I’m amazed anyone thought making a bald eagle a pet would be a good idea.

But Montana Raptor Center attempts to use the permanent residents for good. Permanent residents are trained with workers and volunteers at the Center for education programs. In 2018, Montana Raptor Center conducted 180 education programs in the Bozeman area to teach people about raptors. While it can’t repair the damage that humans have inflicted physically and mentally upon the raptors, it can be turned into a valuable lesson about our relationship with the natural world.

Saying Goodbye

With the abundant land the Center has, I wondered if they were looking to expand their facilities, so the public could see more of the raptors.

Becky Kean didn’t care for that idea.

“We’re here for the birds,” she said, adding, “I don’t want to become a tourist trap.”

I think that seems to sum up what the Center is all about. They’re here for the birds. They want people to learn and be interested in the birds, of course, but their number one priority is helping them, not turning them into a spectacle.

“It must be hard saying goodbye to them when they’re released,” I said.

Becky shook her head.

“Nope. We get happy tears, but it’s good to see them go. That’s what it’s all about.”

If you encounter an injured or orphaned raptor, immediately call the Montana Raptor Center at 406-585-1211. If you would like to support the Montana Raptor Center, they’re always in need of surplus game meat and fish to feed to the raptors. You can also donate online at Donate.MontanaRaptor.org, or by mail to P.O. Box 4061, Bozeman, MT 59772.