Moonshine Tales: Art Lenehan, Jake Mast, Seth Bohart

In December 1918, Prohibition went into effect in Montana. Interestingly, anti-liquor laws were introduced and ultimately revoked earlier in the Big Sky State than in the nation as a whole. In Montana, Prohibition lasted from the end of 1918 until 1926, while national legislation was enforced from 1920 through most of 1933.

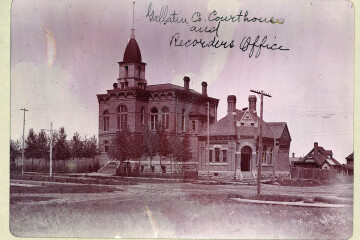

During Montana’s eight years of restriction, several hundred people were arrested for alcohol-related offences in Gallatin County. Jail inmate registration books in the Gallatin History Museum’s archives frequently list individuals serving short sentences for crimes like “possessing moonshine,” “transporting moonshine,” “liquor violations,” or “bootlegging.”

The following excerpts were taken from 1975 interviews of local individuals as part of the Gallatin County Bicentennial Project on Oral History. In these extracts, each interviewee shares his experiences and memories from Gallatin County’s Prohibition era.

Art Lenehan

Born in Iowa in 1906, Arthur Lenehan grew up in Montana; as a young man, he worked for the Forest Service before settling near Salesville (Gallatin Gateway) in 1925. Lenehan farmed and ranched in Gallatin County the rest of his life. He passed away at age 82 in 1988.

Art Lenehan: I moved up the Gallatin Canyon and lived on a ranch up there at Castle Rock Inn for a few years; I had a few milk cows. I used to do quite a bit of hunting, and I raised a garden. I did a little horseshoeing and things like that to try to make a nickel. Times were pretty scarce… I had a patch of potatoes down below the house; I was out working the field one day and a couple of cars came by with the sirens a-blaring. Two fellas in the front car waved at me and I found out [later] they’d robbed the bank down in Bozeman. The law was right behind them and they finally ran them down, shot them, and killed them both. They got the money all back. They had quite a little manhunt to round them up… kind of had me worried—I had a little whiskey still going up there in the canyon and they [law enforcement] were hunting all around it. I was afraid they might find it, so I wanted to stay away from there.”

Interviewer: Weren’t stills a little bit illegal then?

AL: Just a little; they’d put you in jail for a month and charge you a couple of hundred dollars if they caught you. After you got back, you’d just go back to running it again.

Interviewer: Did you make the still yourself?

AL: No, you bought the still. You could have them made at Bozeman, but you generally bought them. You had to buy a little corn and sugar and yeast, and a barrel or two, and mix the corn and the sugar and some yeast and some hot water together in the right portions, and that made your mash. Then you’d put it in a copper kettle and put a fire under it, and there you had your still going.

Interviewer: Did you ever get caught?

AL: I never got caught. I came pretty close one time at least. I went out to cut some wood and I saw the door to my cabin go open. The revenue man [government agent enforcing Prohibition laws] opened the door; I saw who he was, so I just gave it to him.

I left and never went back.

Interviewer: Did you drink the whiskey for your own use, or did you sell it?

AL: I didn’t drink then, so I sold it. I just wholesaled it in keg lots—five-gallon kegs, and ten and fifteens, and maybe twenties. I got about four dollars a gallon for it at that time. It wasn’t too much, but it was better than nothing.

Interviewer: Was whiskey really strong? More than today?

AL: We tried to keep it tested at 100 proof. When we sold it we wanted it to be 100 proof.

Interviewer: How did you test it?

AL: We had a regular whiskey tester and you could tell just what proof it was.

Interviewer: Can you explain how the tester worked?

AL: Well, it was similar to an antifreeze tester. It was a glass tube with a float in it. The higher the bulb floated in the whiskey, the stronger it was.

Interviewer: Was there any danger from drinking the whiskey?

AL: Not our whiskey. We kept our stills real clean. Some of them, however, let their stills get dirty and then there was a lot of fuel oil, and that was really poisonous.

Jake Mast

Jacob Mast was born in 1908 in Nebraska but grew up in White Sulphur Springs, Montana. Jake ranched in both Bridger Canyon and White Sulphur Springs. His moonshine story related here took place in Bridger Canyon during Prohibition. Jake Mast passed away in 1992 at age 84.

Interviewer: What experiences did you have with homemade whiskey?

Jacob Mast: Well, I don’t know if I should tell all those or not… I went up to a neighbor one day and he told me about it. His wife was mad at him and he finally reached behind the chair and said; ‘Here, do you want a drink?’ He pulled out a quart bottle of whiskey and said; ‘My neighbor’s still blew up and I went up and soldered it for them, so they gave me a gallon of whiskey for it. My wife is mad at me now, but she’ll get over it in a few days.’

Interviewer: Did anyone ever come up checking on whiskey in these places?

JM: Well, I guess it had been checked on the place I moved on [to]. I found the still out in the brush and it had big holes slashed in it, so the revenue men had been there. When I leased the place, I had to go to the jail over in Helena to make my deal with the man that owned the place. He was in jail for moonshining.

Interviewer: So, there was some activity there.

JM: There was, but I don’t know how much. It wasn’t all in the open, you know. Most of it was undercover. You’d just get a little bit of it here and there. You knew it was going on but you didn’t know how much, not on any big scale, I think. Just enough to buy the groceries and pay the rent, you know.

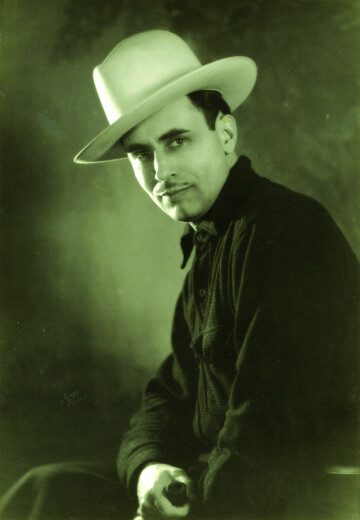

Seth Bohart, circa 1940

Seth Bohart, circa 1940

Seth Bohart

Seth Bohart was a prominent Bozeman lawyer who served as Gallatin County Attorney. He graduated from Wilsall High School in 1920 and attended Montana State College. During World War II, he served in the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps. Seth Bohart passed away at age 80 in 1978.

Interviewer: What experience did you have with moonshiners and their product?

Seth Bohart: My first and only experience was with the product; I had no particular dealings with the shiners. I was probably about sixteen years old, and on one Sunday there were about four or five of us riding our horses together. Perhaps we were going to or from one of the impromptu rodeos. One of the older fellows pulled out a bottle of moonshine, took a drink of it and passed it around to the others, and finally it was my turn. Since I had not had any experience up till then, I tipped the bottle up and started to take a drink like it was water. I immediately choked and gagged while we were riding at a gallop. I swear, when I started to cough, the stuff ignited and I was blowing fire between my horse’s ears.

Interviewer: Would you tell me where some of the stills were located up there [Bridger Canyon]? Do you remember where they were?

SB: There were several different locations… As a matter of fact, there existed one on my place, where Bridger Creek goes under my west boundary fence. And although it was only a couple hundred yards from the Bridger road, the area then was completely covered with dense, heavy growth of lodgepole pine. So, it could not be seen or noticed from the road. I have found at another location a half a mile from there, the remnants of an old oak barrel. There was a man by the name of Palmer who had made some [moonshine] over on the north side of the Bridger divide. He apparently became despondent, maybe from drinking too much of his own product, or poor business. He shot his [horse] team, then set his cabin afire and killed himself…

Much later than that, and shortly after I became county attorney, we had an incident on Stone Creek, which would be east of Bridger Canyon Road. There were two moonshiners living in a cabin in the wintertime, and they got in an argument, and one of them shot the other in the leg. At that time, I was having a little vacation as a result of a broken leg, and a man by the name of Mr. Bunker was my deputy—Gene Bunker. He and the sheriffs [deputies] went up to investigate the affair, and the premises. They found about thirty-two barrels of mash in the cabin, and a certain amount of moonshine, or whiskey. Mr. Bunker went to the hospital to get the story of the man that was injured, or shot, and then attempted to obtain a dying declaration in the event that he did die, so that we could successfully prosecute the other man. But he was of such a character he would not admit that there was any possibility of his dying. Instead, he said he would take care of ‘that so-and-so’ when he got out. But he did not. He died as a result of the injury before he ever got out of the hospital, and there was, of course, no chance to successfully prosecute the other bootlegger.

Interviewer: Would you tell me the story of the moonshiner who had to walk home in a bad condition?

SB: There were three brothers that lived down Brackett Creek, a distance of about five or six miles from the forks of the road, as we called it, where the Bridger road forks with the Sedan road. This was in midwinter, because the snow was very deep. It was very cold. This man [one of the brothers] was driving a team with a jumper sled (just a box on the front runners of a bobsled), returning from Bozeman [thereabouts]. He had with him a gallon jug of moonshine. At a point on the road just south of the forks of the Brackett Creek roads, on the south fork of Brackett Creek, the old roadway ran very close to the edge of the creek. And the creek bank in that area was rather deep and steep. Whether it was his driving or an accident of the horses, they got off of the packed portion of the trail, fell into the creek, and the team drowned. He was so full of whiskey that he undressed, all except his long underwear, and walked into the ranch home several miles away in his underwear with this gallon jug of moonshine over his shoulder. That’s the end of that trip.