Disgraceful Shacks and Fire Traps: Carnegie Library

Most of Bozeman’s citizens can identify the Carnegie Library that still stands proudly on the corner of N. Bozeman Avenue and E. Mendenhall Street. Not many could tell you that it is located at the terminus of the city’s historic red-light district. The library’s history is intimately tied to that of the district that existed on E. Mendenhall Street from Rouse Avenue to N. Bozeman from the 1870s to 1918. The library’s potential location was a hotly debated topic when, in 1901, the city’s application for funds from Andrew Carnegie was approved. Many felt that the location chosen was too close to the tenderloin and its houses of “ill-fame.” Between 1901 and 1922, Bozeman was one of seventeen Montana towns that were granted funds from Andrew Carnegie, the Bill Gates of his day, to build libraries. Of the original seventeen, fifteen remain; many are still functioning as libraries, although Bozeman’s library is currently used as a law office.

Andrew Carnegie was born in 1832 and arrived in Pennsylvania from his home country of Scotland in 1848 at age thirteen. He began working right away in various jobs. His one respite came through the gift of knowledge, when Colonel James Anderson allowed Carnegie and other working boys access to his book collections. By 1892, Carnegie had become the wealthiest man in the world. He felt that the rich had a moral obligation to give back to the world financially. It became clear just how influential Colonel Anderson’s gift was when Carnegie decided to donate the funds to build a free public library in his birthplace in Scotland. Carnegie had found his philanthropic niche. He funded 1,687 free public libraries in the United States alone from 1886-1923.

The Carnegie Library was not the first public library in Bozeman. The Bozeman Avant Courier reported in 1872 that the Gallatin County Bar Association was making an effort to institute a public library. They founded a Young Men’s Association (YMA) to take charge of the endeavor. It was clear that the importance of the library was moral as well as academic when the Courier stated, “it will give our boys and young men some place besides the saloon and gambling house to spend their evenings and leisure hours, in storing their minds with useful instructions.” Due to an economic downturn, that first library disbanded in December of 1875. The collection was eventually moved to a public school. In 1884 the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) received funds and inventory from the YMA, and took on management of the library.

The belief that the library was an antidote to vice available to men continued, and foreshadowed the eventual location of the Carnegie Library. The Bozeman Weekly Chronicle published this opinion: “There are a great many young men, and even many of mature years, floating around without any home, without any place to spend an evening, at least in any profitable manner, who would be glad to avail themselves of the advantages offered by a reading room.” Considering that, at the time, there were four “female-boarding houses” located along one block of Mendenhall and the alley between that street and Main, it may not have been simple conjecture that additional PG entertainment was warranted. Joseph M. Lindley

Joseph M. Lindley

The YMCA library was closed in 1888; by 1900 the city had a successful library with a collection of around 5,300 volumes. In October of 1901, Bell Chrisman, head librarian, and Joseph M. Lindley, the city library committee’s chair, applied to Carnegie for funds for a new library. In March of 1902 they were approved for $15,000 for a building. The next month, Lindley received three books on the subject of libraries from Carnegie. It was noted in the newspaper that these books showed that Mr. Carnegie had given money to establish libraries “for other classes of people besides his own Anglo-Saxon race.” Carnegie funded the building of many libraries for African-Americans when they were legally prevented from using white libraries due to segregation.

The potential location for the new library was immediately contentious. In July of 1902, there was a “Lively Session of the City Fathers Thursday Night,” and although the library site was discussed, no choice was made. About the only thing the council could agree on was that the site should be on a corner, and be in a “central” location. Where was central?

Demonstrating that nothing much changes, there was a debate about Bozeman’s directional growth. When Nelson Story, Jr. said the library should be on the west side of town because that was the way it was growing, Lindley and alderman Apollo J. Busch were “under the impression that [Story] did not know very much about the growth of their town.” Multiple sites were suggested, including one owned by the senior Nelson Story at the corner of Bozeman Avenue and Babcock that was on the table for $4000. The discussion was heated. When asked by alderman Thomas H. Rea if his preferred site was on a corner, Lindley responded, “he ought to go over the city as to be able to know where the city sites were.” Rea moved to adjourn the meeting while Lindley was still speaking. No decisions were made. No mention of the building at 234 E. Mendenhall was made, although that location was well known as the building that had been built by Lindley specifically to be used as a brothel in 1891. When he failed to make the mortgage payments, Nelson Story Sr. successfully sued him to take possession of the house. He did not evict the tenants or put a stop to their business.

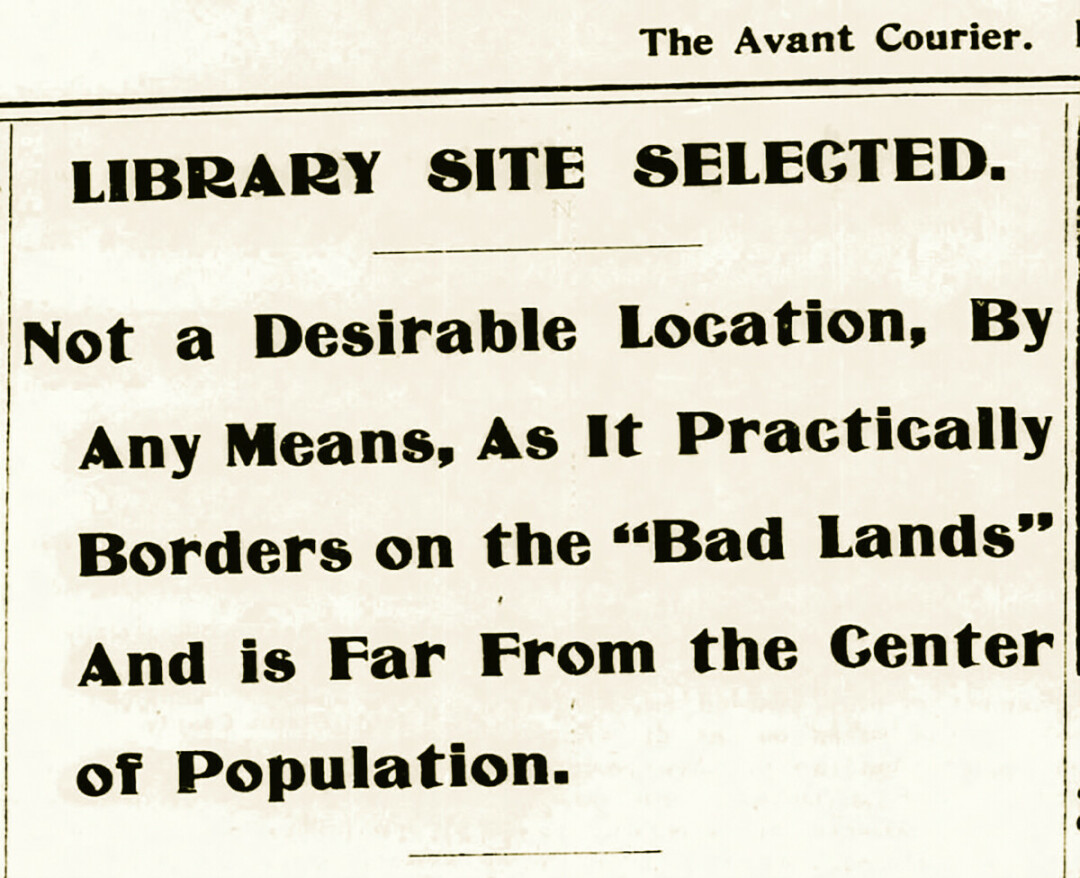

The council remained undecided between two properties until the end of July 1902. The deadlock was broken by Mayor Morris’ vote. The location on the corner of N. Bozeman and E. Mendenhall was immediately panned. The Courier reported, “Library Site Selected: Not a Desirable Location, By Any Means, As It Practically Borders on the ‘Bad Lands’ And is Far From the Center of Population.” The Courier went on to chastise the city council for a decision based on money, not on the suitability of the location. The property was purchased for $900, a mere $1600 less than the site proffered by Nelson Story. The Gallatin County Republican took the initiative to poll local citizens on the location. Respondents included J.V. Bogert, who had this to say; “[I]t is disgraceful… I cannot image what the council was thinking,” and C.M. Bromley, who observed; “It is not a very nice place for the children to visit.” R.D. Steele summed up the sentiment, saying; “[T]hey could not have made a worse selection.”

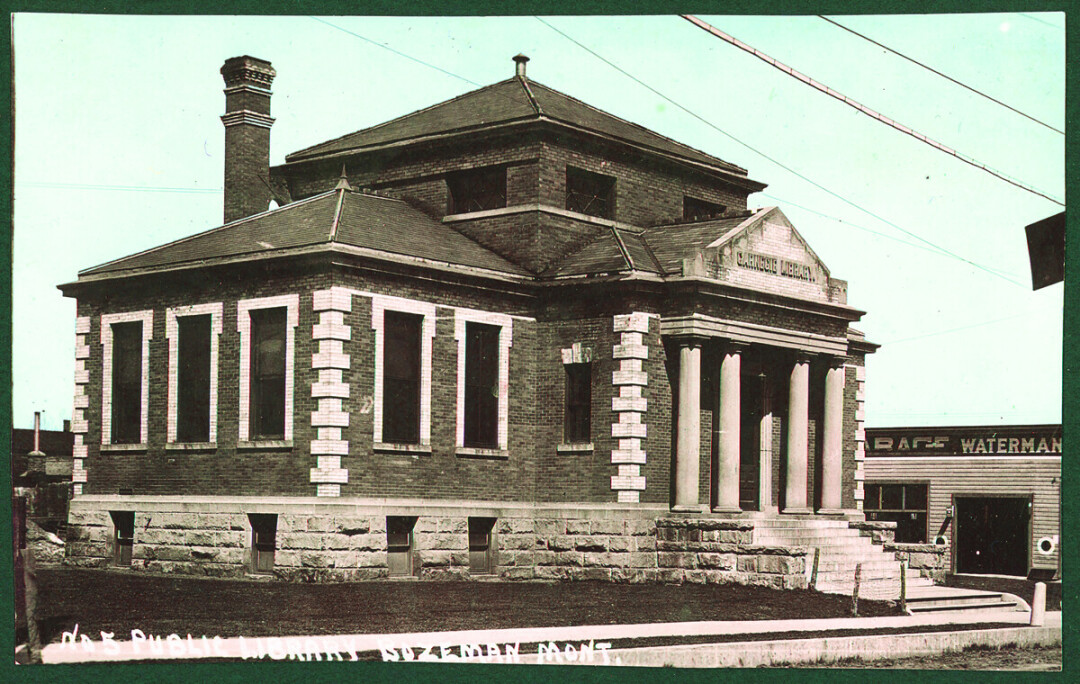

But the decision had been made, for better or worse, and the city moved forward, securing Charles S. Haire as the architect in August of 1902. The Bozeman building would be Haire’s fourth library commission in Montana since 1900. It was built in a Classic Greek-inspired style, and contained reading rooms and a basement with a large meeting room. The library was officially dedicated on January 19, 1904. It was open every day from 1:30-5pm and 7-9pm, as well as Sundays from 2-5pm.

Some felt that although the site was undesirable, putting the library there was a good excuse to clean up the district. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union campaigned to have the brothels shut down, arguing that innocent young people had to walk close to the houses of the “soiled doves” to visit the new library. The campaigns to ban liquor and the sex trade were closely linked. Despite this pressure, the district and its trade persisted. The Courier reported in 1905 that the new and handsome building was within a few feet of “the shabbiest looking shacks and sheds to be found anywhere within or without the city limits.” In 1910 the Republican Courier was still bemoaning the location and warned that the “undesirability of the locality surrounding the library may well stand out as a horrible example of what factionalism and bull-headness will do.”

The red-light district was eventually shut down, in 1918. The Carnegie Library has persisted. By 1979 Bozeman’s population had outgrown the collection capacity of the building. Citizens voted to build a new library, which opened in July of 1981, marking the end of an 80-year run for the Carnegie library. Much like the business of borrowing books did not disappear, nor did that of the “demi-monde” — they simply shifted to different venues. The Carnegie library building housed city offices until the 1990s. Attorneys Mike Cok and Mike Wheat purchased the building and restored it. It still functions as a law office today. Lindley’s house of ill fame at 234 E. Mendenhall also remains, but it now houses the Extreme History Project, an organization dedicated to illuminating the history of Bozeman. Bozeman’s Carnegie Library was built as a legacy building, one meant to last. The building at 234 E. Mendenhall, erected in 1891 as a house of ill repute, was not meant to last, but both buildings still stand, and help us tell the stories of Bozeman’s past.

Vickie Lyons has lived all over the West, but has called Bozeman home for seven years. A member of the Extreme History Project; when she isn’t researching history, she enjoys spending time with her husband and two kiddos, both indoors and out.