What is a Wobbly?

While some in the press have made much of Montana candidate for U.S. Senate Amanda Curtis’s connection with the International Workers of the World, or IWW, perhaps not so much is known about this organization and its history in places like Butte, Montana.

The IWW was founded in Chicago in 1905 (where its headquarters remain to this day), at a convention composed of around two hundred radical-leaning unionists, mainly composed of members of the Western Federation of Miners. In 1893 miners in Butte, Montana, had played a major role in the formation of the Western Federation of Miners. Miners from across the West converged on the Mining City to consolidate regional representation of their interests. The Butte chapter of the WFM emerging from that meeting became Local Number One.

In particular, the IWW was organized because of the belief among many in the working class, that the already-existing American Federation of Labor (AFL) not only had failed to effectively organize them (only 5 percent of workers belonged to unions in 1905), but also was organizing according to narrow craft principles which divided groups of workers, similar to the Guild system of old Europe. The IWW believed that all workers should organize as a class, into, as one of their main mottoes says, “One Big Union.”

One of the IWW’s most important contributions to the labor movement was that it was the only American union to welcome all workers into their ranks, including women, immigrants, African Americans and Asians. The fact that the IWW welcomed both sexes and all peoples into their ranks most likely contributed to the nickname that most IWW members carry with pride: Wobblies. While the title’s origins cannot be proven for certain, the most probable story involves a Chinese restaurant keeper in Vancouver in 1911 who supported the IWW and let its members shop on credit. Unable to pronounce the letter “w,” he would ask if a man was in the “I Wobble Wobble.” Local members soon referred to themselves as part of the “I Wobbly Wobbly,” and by 1913, “Wobbly” had become a permanent moniker for workers who carried the red card indicative of IWW membership. Mortimer Downing, a Wobbly who first explained the title, noted that the nickname “hints of a fine, practical internationalism, a human brotherhood based on a community of interests and of understanding.”

The IWW was condemned by both politicians and the press, who characterized the group as a threat to the market as well as an effort to monopolize labor. Factory owners would sometimes utilize Salvation Army bands to drown out IWW speakers, and violent means were sometimes employed to disrupt their meetings. IWW members were often arrested and sometimes killed for making public speeches, but this violence did not alter the union’s determination to gain their aims.

By 1906, the IWW was making headlines from Pennsylvania to Nevada. The Wobblies also made a stand for free speech that year in Spokane, Washington, which had outlawed street meetings. After IWW organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was arrested by Spokane authorities for breaking this ordinance, dozens and dozens of Wobbly members and supporters came to the location and invited the authorities to arrest all of them, a tactic aimed at emptying the city’s coffers as they made arrest after arrest. Over 500 people went to jail and four people died during the Spokane incident.

By 1912, the IWW had around 25,000 members, mostly concentrated in the Northwest. These included dock workers, agricultural workers in the states, and miners and textile mill workers. The IWW’s efforts were met with “unparalleled” resistance from Federal, state and local governments, from management, and from groups of citizens functioning as vigilantes. the violence intensified. In 1914, Wobbly Joe Hill (born Joel Hägglund) was accused of murder in Utah, found guilty on flimsy evidence, and was executed in 1915. On November 5, 1916, in Everett, Washington, a group of “deputized businessmen,” led by Sheriff Donald McRae, attacked IWW members on the steamer Verona, killing at least five union members (six others were lost and never accounted for).

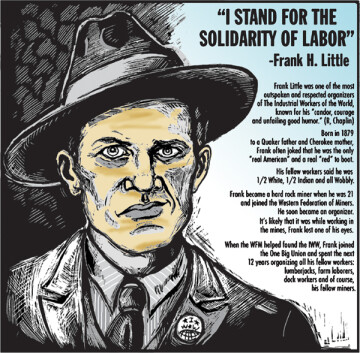

In 1917, the International Workers of the World (the Wobblies) attempted to organize Buttes’ copper miners into a larger vision the Wobblies had of “One Big Union.” Frank Little, a veteran organizer for the Wobblies, arrived in Butte in mid-July to take on the task. The Wobblies vision of workers controlling the means of production wherever they successfully organized did not sit well with the Anaconda Company, which virtually controlled all mining (and other business ventures as well) in the town.

The United States had entered the First World War earlier that year, and a general anti-war sentiment among the mostly-European immigrant workers in Butte was also making the Company nervous. When Little insisted during public speeches in the Mining City that workers had more in common with one another than with the capitalists he said started the war in the first place, he may have gone too far. On August 1, Little was taken into “custody” by men identifying themselves as police officers, beaten, dragged from behind a car, and left hanging from a railroad trestle. No murder convictions, however, resulted from his murder. The Wobblies continued to try to organize in Butte, but without much success. After an attempted strike at the Neversweat Mine in 1920 ended in gunfire and death, the Company also banned members of the IWW from their mines.

Despite efforts to combat the organization, the IWW has held on. As of 2005, the 100th anniversary of its founding, the IWW had around 5,000 members. There are IWW branches in Australia, Austria, Canada, Ireland, Germany, Uganda and the United Kingdom. The Portland, Oregon, General Membership Branch is one of the largest and most active IWW groups around these days. The branch has successfully supported workers wrongfully fired from several different workplaces. Due to picketing by Wobblies, these workers have received significant compensation from their former employers. Branch membership has been increasing, as has shop organizing. The Portland GMB also hosts social and educational events, notably Music for the Working Class, a free event that occurs on the last Wednesday of every month. The branch annually hosts a month-long Wobtoberfest, a series of music shows, film showings and educational events each October.