Snow Hazards and Ski Tracks

On a warm and sunny October morning I load up my bright yellow Trimble pelican case into the back of Dr. Jordy Hendrikx’s red SUV with a “Snow Science” sign on the side and hop in the passenger seat to head up to Big Sky for some GPS field work on the Lone Peak rock glacier.

Dr. Hendrikx chats with me about his research, family, and Montana to pass the driving time from MSU to the top of the ski hill. Upbeat and friendly, his Kiwi English accent growing thicker at times when he liltingly rolls his R’s and occasionally slips in words like “keen”. While interested in this study, his real passion is in researching snow and avalanches. “I call myself a snow scientist, that’s what I do. I look at snow as both a resource and a hazard.” While he’s interested in the resource of snow both as a water source and as a business opportunity, what he is really interested in is better understanding the hazards that snow creates in the form of avalanches.

“I’m saddened every time that I see a fatality report and I see situations where there is information for them to make better decisions, like an avalanche forecast in a given area, and for some reason they’ve ignored it or they didn’t know it was there” he says.

Hendrikx has spent his entire life dedicated to snow. Knowing since he was a boy that he wanted to work in the mountains he graduated with a B.S. in Geography and Geology from Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand as well as a B.S. in Physical Geography there. He then earned a Ph.D. in Geography at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch. He has lived in Bozeman with his wife and two young kids, conducted research as the Director of the Snow and Avalanche Laboratory, and taught as an Assistant Professor of Geography at Montana State since 2010.

“One of the reasons I came here is I can spend more time looking at snow and avalanche work. Snow avalanches are big issues here in the US and they kill about 35 people per year which is a significant number and it closes roads and stops businesses from operating” he says. He adds that while he can still research avalanches in New Zealand, the mountains there are less accessible to people and the seasons are milder. “We’ve got that really strong seasonality here when it’s winter then we’ve got winter snow all the way down the hills and people have got easy access to the mountains.”

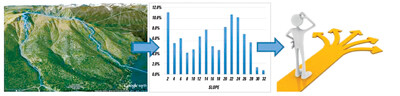

His current work concentrates on how people can be educated to make better decisions in the backcountry. “What we’ve found is people can know a lot about snow science and understand the crystals of snow and so forth but they can still make stupid decisions.” This project called Tracks: Understanding Travel Behavior in Avalanche Terrain is a unique crowd sourced approach to data collection that lets participants use a smart phone app called Ski Tracks to record data on their back country ski and snowboard trips. The app records their speed, distance, slope, duration, and vertical ascent in addition to geographic location. The data from Ski Tracks is then combined with a pre and post interview to help understand their decision making in the backcountry.

To give me an example he says “Imagine you’re got really unstable snow [and] I head out with my wife and child. The sorts or decisions I make are likely unfortunately different if I head out on that same unstable snow the next day with a group of young men. So my knowledge of the snow is no different but my decision making process and the group dynamics of that process are different.”

Kyla Sturm, a Snow Science student who did data analysis for Hendrikx explains the project, “Most studies done on avalanches, they occur after the avalanche has occurred, after a fatality has happened. [This study] is trying to look at the behavior of people before the avalanche occurs to see if we can get any different knowledge, or more knowledge about them to prevent it. Does human interaction and behavior actually make a difference in a group dynamic?”

The goal of this research, which is done with the help of a social scientist, is to understand why people may make poor decisions that can get them killed depending on who they’re out in the backcountry with. Hendrikx says “I think that’s a really paradigm shifting view on avalanche science because rather than just saying that we need to fill you with more science, yes we need to give you some science, but we also need to make you aware of the failures that you’re making in your decision making” adding that “If we get a better understanding of that than we can actually focus our education more towards recognizing these human pitfalls.”

Even at the top of his career he never forgets to appreciate the contributions his students make in furthering his work. “I’ve had some fantastic undergraduate scholars that have done some neat work helping out and developing some of the systems that we use to analyze our data.” When it comes to his graduate students he says “I’m usually surprised by their desire and motivation to just get out there and collect little bits of data, its hard work to collect data and we’ve got huge amounts of data coming in.”

So why Bozeman Montana? In addition to the accessibility to our stunning mountains and the unique geography here in Montana another thing that drew him here was the avalanche focus of MSU’s snow science program. “In New Zealand we could certainly attract some good graduate students but we weren’t specifically known for this type of work, but here when people want to do snow science and they’re interested in avalanches then they come to Montana.”

As a world traveler that spent part of his childhood growing up in The Netherlands, England, and Switzerland before his family settled in New Zealand, he says he loves the town of Bozeman, especially the preservation of our downtown history and culture. “We have the shop selling Stetsons and handguns right next to the coffee shop, we’ve got that juxtaposition of cultures that I think is very refreshing.”

Whether out on skis, in the classroom, or educating the public Dr. Jordy Hendrikx loves every minute of his work. His driven nature and enthusiasm for mountain environments gives his work both a purpose and a passion that I have rarely experienced in others.

For more information on the Tracks Project or to participate you can visit www.montana.edu/snowscience/tracks.