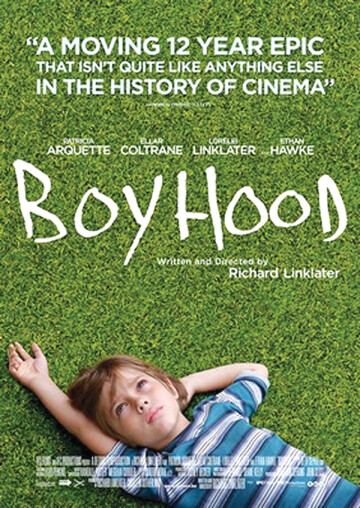

Boyhood

A Period Piece For The Near Present

From the outset of his career, director Richard Linklater’s films have been preoccupied with the passing of time. Frequently, these films are structured around a 24 hour period. Slacker, his debut feature from 1991, was a sort of relay-race of a movie, with the narrative baton getting passed from one group of sermonizing Austin-based slackers to another over the course of a day. The Before Trilogy (Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, Before Midnight), staring Ethan Hawke and Julie Deply, charts a relationship from its romantic inception to its shaky mid-marriage period. Each film is set over a day (often less) with an entire decade separating each production. They’re the ultimate walk-and-talk films, but are naturalistic and engaging. They feel very real.

His follow up to Slacker, Dazed and Confused, a coming-of-age film disguised as a stoner comedy, follows the lives of incoming high school seniors and freshman on the last day of school in 1976. Between the drinking, smoking, chatting and driving, are moments of clarity, small epiphanies between the chaos of a last day at school. The film isn’t as interested in exploiting its stoner credibility or its period setting as it is in exploring the small moments the characters share with one another, the seemingly minute moral decisions that shape who we are. Linklater’s previous films and now Boyhood, his latest, reside and flourish in these moments.

Boyhood is, simply put, a story about a boy and his family growing up, shot over the course of twelve years (2002-2013) with the same actors. Ellar Coltrane stars as Mason Jr., a quiet and observant boy who lives with his sister Samantha (played by Lorelei Linklater, Richard Linklater’s daughter), and his divorced parents Olivia (Patricia Arquette) and Mason Sr. (Ethan Hawke). The family moves, Olivia attempts to secure a better future for her kids, Mason Sr. gives advice from his position as the “weekend parent”, friends and step-parents come and go, Mason enters high school, Mason enters college and the movie ends. Though the film runs at almost 3 hours it allots to omit much of the capital-I-Important moments like his first kiss, losing his virginity or what-have-you.

Instead these cliche moments of self-discovery are replaced with glimpses of high school keggers, a weekend camping trip, bowling with Mason Sr., walking home after school when his sister refuses to pick him up. Structurally the film resembles the way our memories work when thinking about our own childhoods, how little moments stick out and sculpt us into who we are. The moments where the film does develop something resembling an arch are distinct if not a little out of place. Olivia’s attempts to become financially stable and go to college land the family with a troubled, alcoholic professor for a step-dad. This part of the film, though as intense and awkward as such a situation would be, seems out of place.

It is fortunate however, that this clunkiness is mitigated by Arquette’s performance. Though Hawke does a stellar job as the goofy, largely absent parent of the two, he is given the bigger moments with the kids and is allowed to have fun with them. As the caretaker parent Arquette’s performance requires a delicate balance between her tenacity, tenderness and fallibility which she pulls off perfectly. There is a moment near the end of the film where she laments the anti-climatic moment of Mason’s moving out, it’s understated, and one of the most moving scenes of the year. There are few films made in America today that portray single mothers without a single ounce of judgment or pity, and her story alone helps launch the film to above its already impressive, groundbreaking feats.

The most remarkable part of the film really is the way in which weeks, months, and even years can pass with a single cut. Though Boyhood is not alone in the pantheon of films which depict a character growing with his/her actor (There’s François Truffaut’s fictional surrogate Antoine Doinel, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud in five films over the course of twenty years, and The Harry Potter films, which the kids in Boyhood attend a midnight book release for), it is the fluidity with which the time passes that makes the movie so breathtaking. Aside from the occasional growth spurt, the changes that wash over Mason Jr.’s face are so gradual that you’ll find yourself, like a distressed parent, wondering where the time went. Linklater and his editor omit any use of dates and text to ground show us the time. There is the occasional cultural marker however: specific models of Macintosh computers and Gameboys, Mason Sr.’s rants about the Iraq War and forcing his kids to put Obama signs in the street, and songs from Soulja Boy, Coldplay and Vampire Weekend do help to orient the viewers. But these pop cultural relics don’t feel forced in as much as they feel like an accidental recording of history, why omit these things when this is what real people were doing, interacting with, talking about and listening to over the past twelve years?

It is this sense of authenticity which makes the film so beguiling and beautiful. Linklater understands that life is an accumulation of mundane fragments, but he makes these mundane moments compelling through the context of an entire adolescence. He shows how a distrust in male-authority can instilled though the nonconsensual buzzing of a child’s hair, or how a kid poking a dead animal displays the potential for an opinionated and inquisitive mind later on. Mason Jr. begins as a quiet boy and emerges as a charming and thoughtful, if not weird and lanky, 18 year old. Compressing a complete childhood into a three hour film is daring and it works, it was the shortest three hours of my life.

Many people my age (born in the late eighties to mid-nineties) will look at this film and see aspects of their life reflected through Mason and Samantha. Many parents will be able to look at the parents in the film and see their own struggles and foibles, but the film transcends these ways of seeing it. Boyhood, perhaps more than anything else before it, earnestly depicts actual life.

Boyhood was screened by the Bozeman Film Society on December 18th. It will be available to rent and buy on January 6th.