The Real John Bozeman With sneaky ways and low morals

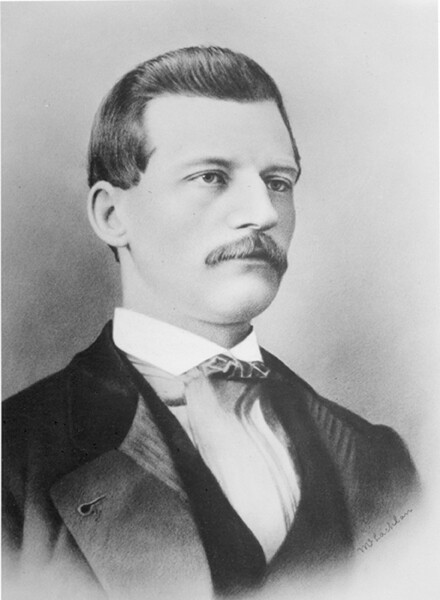

Guess who our town is named after? Some guy called Bozeman? Right! John Bozeman, a rugged mountain man who fought bravely to tame the West, only to be killed by Indians at the age of 32. It’s fitting and deserving that our fine town was named after him. But hold on to your cowboy hats, because you’re about to hear ALL about him, like it or not.

To begin with, he was born a long time ago in a place far away, and by that I mean in 1835 way back east in Georgia. Everything was uneventful until 1849, when his father got a fever…gold fever, and nothing was going to cure it but a trip out west. And like many other men of the day, he left his family to fend for themselves and took off to make his fortune in the California gold rush, saying “I’ll be back before you know it!” They never heard from him again. To put it mildly the whole thing was a bit of a downer for the Bozeman Bunch, but in due course, John got married and had three children of his own. He must have been thinking about that ne’re-d-well dad of his, leaving everyone without a thought and chasing gold. And what he was thinking was “you know, that’s a great idea!” and in 1860, he did the same thing.

He assumed (rightly) that the gold in California would be pretty well picked over, and so after hemming and hawing, decided to try his luck in Colorado instead. By the time he arrived, however, all the good spots were taken. “Well, this sucks!” he thought. “Guess I’ll keep heading west.” He eventually landed in Montana, and even though the A&W was still a hundred years in the future, he set down roots near Deer Lodge.

There was gold in them there hills, and now he finally had a chance to work at getting his share. He tried it and he didn’t like it. Panning for gold is not as easy as it looks, and it didn’t take Bozeman long to discover that standing around in cold water all day long was back-breaking work and was not his cup of tea. “This also sucks,” he thought grimly, and cast about for an easier way to make his fortune. He was a Southern gentleman, after all!

By early 1863 he found himself in the Gallatin Valley for the first time. At the three forks of the Missouri a little town had sprung up, and he staked a 160-acre claim. He soon realized that he wasn’t the only one with gold fever. Soon, thousands of prospectors and their families would be moving west. At that time there were only two routes to the Northwest, both between a rock and a hard place. The first was to travel up the Missouri and then go by horseback to the mines (painfully slow), and the alternative was to try the Oregon Trail (through miles of dry country and Indian territory). If he could find a quicker route, the immigrants would take that one, and he could fleece them – er, I mean they would pay him - to guide them through. As it happens, he met a very ornery guy named John Jacobs who was already in the business of guiding wagon trains through the area, and the unlikely pair set off to blaze a new and quicker trail.

After a number of attempts that were thwarted by bad luck and Indians, who were more than a little put out by the endless stream of pioneers helping themselves to the land, Bozeman managed to bring wagon trains up from the Yellowstone River and over Bozeman Pass. In order to drum up business, the six-foot-two man would dress himself in buckskins and do the whole Wild West thing (“You can see by my outfit that I am a cowboy!”), although ordinarily he liked to cut a dandy figure, complete with striped pants and a cotton coat with an in-fashion slouch hat. Very (18) Sixties!

By 1864 the Bozeman Trail was well established, and the little town of Bozeman, about six shacks big, was officially born. It featured a main avenue of mud, and some outlying fields of mud, and some other minor roads of mud. In other words, it was the Big City of the area. Bozeman tried his hand at farming his stake (which sucked) and also ran mail to and from Virginia City. But even way back then, everyone who wanted to live in Bozeman needed to have at least three jobs, so he also started a business with Thomas Cover to build a bridge and run ferry boats across the river east of present-day Livingston.

John Bozeman was the epitome of the typical Southern riverboat gambler (although he did his gambling in a saloon), with sneaky ways and low morals. A contemporary of his, W.J. Davies, said that “to beat a man out of his wages or to neglect paying a bill or jumping a man’s claim were matters of little moment with him.” And yet, he never ran for politics. Go figure.

As if being a rambling, gambling man wasn’t enough, Bozeman also had an eye for the ladies, and that was really risky business. In a small town with just a few dozen women, whispering “lose the zero and get with the hero” was asking for trouble. He apparently also had a hand in helping unwed mothers get their start. For instance, he pounded on the door of one lady in the middle of the night and pleaded with her to come to his cabin. There was no hanky panky, it was far too late for that, because in the cabin a woman was giving birth to a baby. Mother and baby were fine but were never seen again.

About this same time, Bozeman had been making frequent trips to the Cover’s cabin, making plans with Thomas concerning their business ventures, and to put the moves on Cover’s wife, Mary, it seems. At least that’s what Cover thought. He should have told Bozeman, “Dude! Quit acting so sketchy around my wife,” but instead he bided his time and steamed. And schemed. Then, in April 1867, he told Bozeman that they needed to go on a little trip together to see if they could make some deals with the military forts stationed near the town. Bozeman had a guilty conscience (for good reason) and tried every excuse in the book not to go.

“Gee, I’d love to go, but I think I caught consumption (cough cough).”

“My horse is in the shop with a flat leg.”

“I’m pretty sure I left the stove on in the farthest reaches in my 160 acres.”

But Cover just glowered and said menacingly, “No. I insist you go.”

In the weeks before the trip, Bozeman was anything but happy. A dark cloud had settled over him and he even gave Mrs. Frazier, whom he was boarding with, instructions to send his gold watch to his mother, if he didn’t come back. He must have known that his womanizing ways had finally caught up with him. In fact, on the morning of April 17, 1867, Billie Frazier, the young son of the couple managing the boarding house, looked out the window to see Cover and Bozeman, mounted and ready to take to the road. He heard his mother say to his father, “Isn’t Bozeman a handsome man?” to which his father shot back “Yes, and take a good look at the son-of-a-bitch as this is the last you are going to see of him!”

The two men stayed that evening at the cow ranch belonging to Nelson Story by Livingston. Bozeman bunked with his best friend, William McKinzie, but was still a bundle of nerves. He even offered his friend his outfit, his saddle and his horse to go with it as he desperately tried to get him to take his place. However, McKinzie was dirty after spending weeks among the Indians without a change of clothes, and wanted to get cleaned up, so he refused the offer. In the morning Cover and Bozeman rode off. Nothing more was heard from them until after midnight on the next evening, when Cover staggered into the camp with a bullet wound in his shoulder, stating that Indians had attacked them the day before and had killed Bozeman.

Story, hearing the news early the next morning, was concerned that Indians were preparing to attack his ranch and run off his cattle, and rode to the ranch to hear what had happened from Cover personally. His story (and he was sticking to it) was that after the pair had stopped for their noon meal beside the Yellowstone, five Indians approached them, one with a gun. Cover was all for shooting them (which must have been the way whites said hello back then), but Bozeman thought they were friendly Crow Indians, not Sioux or Blackfoot. When they asked for food, Bozeman changed his mind and muttered to Cover that they were Blackfoot after all, and Cover made a mad dash to the horses to get his gun, leaving his Henry gun near Bozeman. However, before Bozeman could make a move, the armed Indian shot him in the right and left breast and he died immediately. Cover was also shot, and by returning fire managed to kill one of the Indians, and then beat a hasty retreat while the natives took the horses and their dead comrade. Later, Cover snuck back and covered Bozeman with a blanket and walked back to the ranch.

After listening to the account, Story sent his best tracker, Spanish Joe, to the murder site, for a report. A few hours later, the tracker returned, and told his employer that he had checked the area carefully. There were no Indian tracks anywhere. There was no blood, either, except where Bozeman was killed. By the river, he saw Cover’s boot prints and places where stones had been thrown at the horses to drive them away. Bozeman’s prize gun was still there, and he hadn’t been scalped. Something was fishy in the state of Montana, but Story told his tracker to keep quiet about it, as did Story himself.

T.B. Story, in the Fifties, said that his father admitted to him that Cover had shot Bozeman twice in the back, and had then shot himself in the shoulder to make it look like they had been attacked. If the attack had been genuine, the Indians would surely have taken the prize gun, as well as Bozeman’s scalp. Not to mention since both Bozeman and Cover were armed, they could have easily defended themselves. Actually, most of the men in town suspected what really happened, but they couldn’t have afforded an inquest – it would have bankrupted the small settlement (and many of the husbands weren’t too sad to see him out of the way).

To muddy the waters further, a number of years later, a small group of Blackfoot claimed that they were the ones who had killed Bozeman. However, according to Story, the Indians killed many settlers, and to Native Americans, those white guys all looked the same.

So there you have it. John Bozeman, namesake of our town, was killed at 32, most likely on behalf of any number of jealous husbands. He was human, with plenty of greed and avarice in evidence, but he was also courageous and forward thinking. A man of his times. A person who was a bit larger than life, and a fitting person to have a town named after.

A final ironic twist to the tale is that the (alleged) murderer Cover moved to California and made a lot of money. However, he was found dead under mysterious circumstances in the Borego desert. It was assumed at the time that relatives of a man hung by Cover while a vigilante had come to extract vengeance.

Nelson Story erected a monument to Bozeman at Sunset Hills Cemetery, where it can still be seen next to the Story plot.