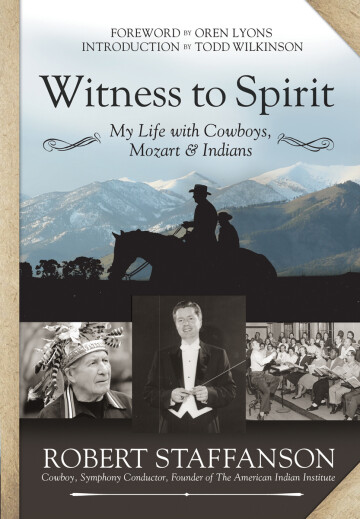

Witness to Spirit My Life with Cowboys, Mozart and Indians

Review of Robert Staffanson’s New Memior

Bozeman author Robert Staffanson has penned an extraordinary memoir you must read to believe. It is courageous: Staffanson today is a civil rights activist battling racism against Native Americans in Montana and around the world. The book is jaw-dropping: unbeknownst to most of Staffanson’s suburban neighbors, he was once a nationally-known symphony music conductor who rubbed shoulders with many of the greats such as Eugene Ormandy, Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Fiedler and Aaron Copland.

All of this and yet Witness to Spirit: My Life with Cowboys, Mozart & Indians is deeply rooted in the very heart of Western cowboy culture, for Staffanson’s unlikely journey begins on a hardscrabble ranch outside of Sidney and continues into the Deer Lodge Valley between Butte and Missoula. The name of his first horse: Injun.

But what truly makes Staffanson’s debut momentous and inspiring is that it’s now arriving at Country Bookshelf and Vargo’s in downtown Bozeman with the author being a spry 93. Yes, Staffanson has written his first great book of his life as a nonagenarian and it makes me want more.

No one I know—or ever met—has undergone radical reinvention the way Staffanson has. But he actually did it twice.

As a Montana native son—not in the most profound sense of being native—he grew up on the backs of horses. Staffanson is a product of the cowboy culture of myth and lore, defined by its brawny mystique, masculine physicality, and quiet, hard-nosed stoicism that fits the stereotype most of us carry in our minds.

He wore denim, leather boots with spurs on the heels, chaps on thighs, riding with hands calloused by rope, tack adorning saddle and yes, a sweat-stained vaquero hat brimmed just over the brow.

During his coming of age, first along the lonesome flanks of the Yellowstone River near the badlands of Sidney, and subsequently near Deer Lodge, he clearly was headed toward just another bucolic cowboy existence.

But along this journey, the rawhide man was summoned to another calling, his ear finely tuned in childhood to an ambient, open-air soundtrack playing in his head. Imprinted on his psyche were the melodies of his father’s fiddle and mother’s singing of prairie church hymns.

From his earliest sanguine memories of childhood—in the 1920s and 1930s— Staffanson recalls a close relationship with the violin that he came to know as intimately as a lariat.

This love affair led the sensitive wrangler to attain a college degree in music at the University of Montana. Against long odds and doubts expressed by others, Staffanson founded the first symphony orchestra in Montana’s largest city and, by fluke of fate, attended a national, invitation-only conductor’s workshop in Philadelphia where the great maestro Eugene Ormandy was presiding.

Totally unexpected, Ormandy took a liking to the young unassuming “cowboy conductor” and opened a proverbial door, seeing in him promise and spirit.

Through that threshold of kismet, Staffanson landed a prestigious conducting post with a renowned regional symphony in Massachusetts. The Springfield Symphony, in fact, commanded a reputation surpassed only by the Boston Symphony.

Under his direction, Staffanson harnessed the talents of an extraordinary assemblage of classical musicians and he met legends like Aaron Copeland and Leonard Bernstein, in addition to other prominent contemporaries in Europe. The kid from the Old Wild West was, in a tuxedo and directing a baton, putting his interpretation on Old World masterworks such as Mozart’s Requiem, Beethoven’s 9th, and Puccini’s La Boheme.

This improbable chain of events alone would make for a colorful story, but it merely sets the stage for Staffanson’s third and final act.

Something inexplicable summoned him homeward from the Berkshires. While on summer breaks from Springfield in Montana, where he savored the return to cattle roundups and riding with his wife, Ann, he forged friendships with Native Americans. Staffanson, in ways he hadn’t before, saw for the first time, intense racism directed at indigenous people by his own culture. And he became ashamed.

As he spent more time in the company of Indians from various tribes, often on reservations, he realized his own life wasn’t complete. Rising consciousness about the abuses of native people and the suffering they had endured as a result of European conquest left him rattled and unable to feign ignorance any longer.

He told his wife he wanted to quit his conducting career and move back West. In the wake of that life-altering decision, he was beset by sudden tragedy. Complications of an illness would, over time, rob Staffanson of most of his hearing, the most valuable sensual asset he had. Paradoxically, he says, it forced him to become a better listener.

Again, his life would take another dramatic turn. It was only while attending a gathering of Blood Indians at a remote camp in Canada, that Staffanson heeded a yearning for meaning that had been percolating inside him his entire life. He emerged, vowing to devote himself to being an ally to indigenous peoples.

Quickly, he discovered the decision would be met with incredulity and suspicion by distrusting Indians and equal astonishment and animosity from close acquaintances in Bozeman’s white society who accused him of betraying his race.

Oren Lyons, a renowned leader, activist and elder in the Onondaga Nation (one of the six tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy) and who today has a close bond with Staffanson, told me. “At first, we didn’t know what to make of Bob. An indication of his character is not that he sought to somehow gain or establish himself as a self-righteous do-gooder, but it is what Bob gave up that demonstrated his intention was sincere. This is what earned him trust and credibility. What he gave up was everything—his career; his power; his prestige and standing, and having to explain it all to his dear partner, Ann.”

In the quest to confront 500 years of genocide committed against the oldest people on the continent, Staffanson and traditional indigenous leaders founded the American Indian Institute and originated an unprecedented concept called the “Traditional Circle of Indian Elders and Youth.” It has opened lines of communication between indigenous cultures globally in ways that never before existed.

Worldwide, native languages are vanishing rapidly, and with them, Lyons and Staffanson say, is a profound understanding and orientation, perfected across thousands of human generations, that offers insight to the secrets of existence—for all beings on sacred earth. Today, at a time of climate change (which was prophesied by native shamans centuries ago), rising unsustainable growth in human population, loss of species, nuclear dangers, and culture clashes born by the destruction of natural systems, heeding native wisdom to avert calamity isn’t a mandate; it is a choice.

Now you, reader, like me, may not have ever heard previously of Staffanson or the American Indian Institute, but I subsequently learned he has interacted with political, business, and spiritual leaders around the world who have been in positions to make a difference for people who have lived closest to the Earth longest.

“Native people from this continent are beloved around the world and it’s something most Americans don’t realize or bother to wonder why?” Staffanson said. “I have seen the interactions in Japan, Russia, European countries, and Africa. There is also a mutual recognition of indigenous peoples.”

With Witness to Spirit, Staffanson proves to be an insightful, articulate and thoughtful author. This is an important, unforgettable book full of wisdom that, once read, will leave you changed in the way you think about America, Montana, the West, native people and potential courses of action in these troubling times.

The book delivers this message to people of the Baby Boom generation and older: It is never too late to make a valuable contribution to humankind.

It imparts this lesson to those in their thirties and forties: If you feel stuck, don’t continue following the same script. Write a new one for yourself.

Finally and most importantly, Staffanson leads by example in giving this hopeful message to young people: Never be afraid of reinvention or taking a stand on behalf of what you believe in.

Witness to Spirit is a reminder for us all of the spiritual transformation that can only happen when we have the courage and moral conviction to open our minds, ears and hearts.

Todd Wilkinson is an American environmental writer who lives in Bozeman. He is author of the new book “Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek, An Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Bear of Greater Yellowstone” and “Last Stand: Ted Turner’ Quest to Save a Troubled Planet.”