Lewis and Clark Caverns Montana’s First State Park

From Private Tourism to National Monument to State Park

We know that Native Americans did know of the caverns hundreds of years ago, as the stories of the steaming mountain are mentioned in their oral histories. Although the caverns are now named for Lewis and Clark, we also know that Lewis and Clark camped within a mile of the caverns on July 31 1805 but did not know of the underground labyrinth of limestone rooms.

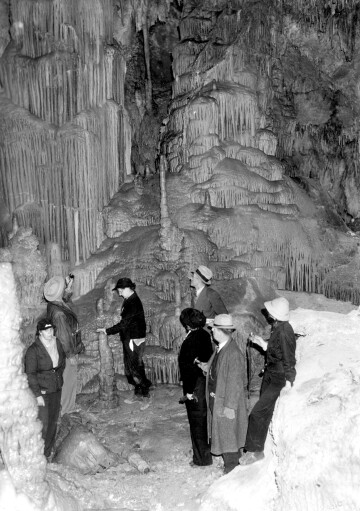

Of Montana’s 300 caves worthy of name, the Lewis and Clark Caverns are considered the most spectacular. The caverns are not just one big cave, like some of the other popular caves in the country, but a series of unique rooms connected by narrow tunnels. Visitors descend 500 stairs and down nearly 400 vertical feet.

In 1882 two men from Whitehall, Charles Brooke and Mexican John discovered the cave entrance. The men had heard Native American stories of the great caves and explored the area to find out for themselves if the stories were true. Neither of the men shared the exact location of their discovery but enough was said that they are remembered in historical records of the area.

Ten years later in 1892 two local hunters, Tom Williams and Burt Pannell, “officially” discovered the cave entrance. One story was, “while they were resting they noticed a plume of steam coming out of the caves” and another story, “they noticed bats flying in and out of the limestone mountain”. The men threw a large rock into the opening and knew that it was deep. Williams always wanted to explore the cave and six years later in 1898 he brought ropes to rappel and candles for lighting and along with six other men, they lowered themselves down into “Discovery Hole”.

In the years immediately following, Williams framed and installed a rope ladder and provided some development work inside the cave. On occasion, he would take parties into the cave, leading them through the strange passage-ways using candles for illumination.

Williams saw the cave’s tourism potential and in 1902 convinced local investor, Dan Morrison, to develop the caverns for tours. Once involved Morrison set to improving the caverns. He delegated his nephew, George Morrison, the task of cleaning and enlarging the lower entrance and building a trail-way through the caverns.

While they were successful in developing and promoting their tourist business, they were doing so on land that was owned by the Northern Pacific Railway Company as a result of the Pacific Railway Land Grant Acts.

In 1864 President Lincoln signed into law the largest of the railroad land grants, the Northern Pacific Railroad land grant. This law conditionally granted public lands for the purpose of building and maintaining a railroad from Lake Superior to the Pacific Ocean. The law gave public lands for a railroad right-of-way upon which to lay the tracks, and 40 million acres (an area slightly smaller than Washington State) to raise capital needed to build and maintain the railroad. The land was granted in alternating square miles, which created a “checkerboard” pattern of ownership that is still visible on maps and the landscapes of much of the Pacific Northwest. This pattern of granting some sections while retaining alternating sections--the checkerboard pattern-- was intended to increase the value to the public treasury of land remaining in public ownership (every other section) once railroad access was provided.

Morrison attempted to purchase the land from the Northern Pacific but failed. He also brought a suit for quiet title but that was dismissed as the land was not surveyed for title. The matter of ownership of the caverns site was conclusively defined on May 11 1908 when President Theodore Roosevelt, acting under the authority of the Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities, proclaimed the 160 acres around the caverns entrance as Lewis and Clark National Monument. A second proclamation was given by President Taft in 1911 which added a survey of the caverns area. This second proclamation sealed the ownership to the Federal Government by locating it exactly and on February 14 1911 Northern Pacific Railway Company signed a quitclaim deed.

Failing to obtain ownership of the caverns property, Mr. Morrison petitioned Congress for $40,000 in remuneration of all services and expenses incurred underwriting the discovery exploration, and development of the Lewis and Clark National Monument. The court rejected his claim asking why he spent money on a project that he knew he held no title. In 1928, Congressman Scott Leavitt introduced a measure to pay Dan Morrison $5,000 as compensation for the work he did on the cave and to pay him five percent of the cavern net profits for a period of ten years. In 1929 Morrison received $5,000 as payment in full for his contribution but was denied any further income.

After becoming a National Monument, the caverns was operated on an erratic basis under the control of the Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, and in 1917 under the control of the newly formed National Park Service. Technically the caverns were closed, with only a custodian and Mr. Morrison holding keys to the locked cave until 1936 when the area surrounding the caverns became a state park.

While the economic depression of the 30’s destroyed many American’s lifes, the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) breathed new life and opportunities for the Lewis and Clark National Monument.

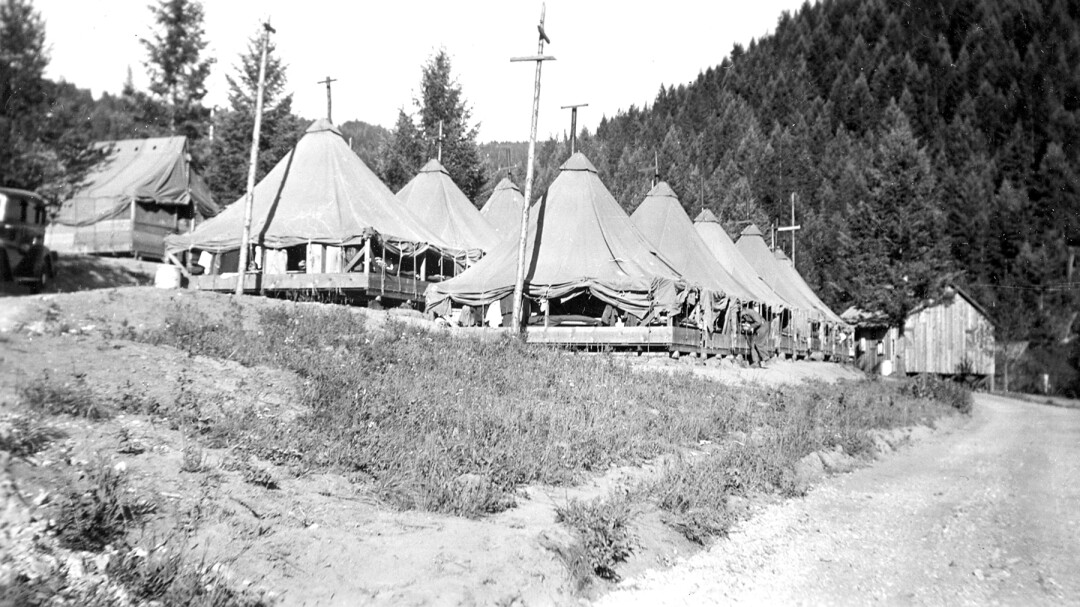

Shadan Lahood, a Cardwell merchant and land owner, was very interested in the development of the caverns. It was through his efforts and offer of property that a Civilian Conservation Corps camp was established in the area and dedicated to furthering the development of the caverns.

From the summer of 1935 until the summer of 1941 there were 175 to 200 young men working in or around the cave. Many improvements were added during this period, including 3.2 miles of scenic highway through Greer Gulch to the parking area, a refurbished picnic area, the stone Headquarters House, and expensive development work inside the cavern. One can still see steps the CCC men carved in the stone floor of the caves but probably the most significant accomplishment within the cavern was the 538-foot exit tunnel that allowed visitors to exit the cavern without having to turn around and retrace the tedious route back through the entrance. All in all it is conservative to estimate their contribution at the time to be worth approximately $2,000,000. At this point the state had provided no funds for the project.

The idea of a Montana state park system started as early as the 1920’s, influenced by the new conservation movement spearheaded by President Teddy Roosevelt. Montana cities were growing and more people owned automobiles, increasing the demand for places to go outdoors.

Before the caverns development could be successfully completed it was necessary to acquire land in the proximity of the caverns. To this end, the Northern Pacific Railway Company deeded several hundred acres of adjacent land, which the Montana State Land Board accepted as Morrison Cave State Park in 1936, the first state park in Montana. The actual cave site and additional land totaling almost 1500 acres was not deeded to the State of Montana from the Federal Government until later in August of 1937.

Visitors were permitted in the caverns in 1938, and in 1940 electric lighting was installed. It was closed during the war years of 1943, ‘44 and ‘45. In 1947, the State of Montana started making annual appropriations for the State Park System.

1947 saw the construction of a concession building, water system and seven miles of power lines, constructed entirely at the expense of the Montana Power Company. That year also saw the addition of a rail-tram system that would take passengers from the parking area up the half mile to the cave entrance, the train was a converted army jeep named the “Dinosaur Jitney”.

The oversight of the park was assigned to different state agencies and with each management change the park was given a new name. In 1946, the Lewis and Clark designation was restored by the State Park Commission, and in 1953 the name was changed back to Morrison Cave State Park by the State Highway Commission. Later a petition was filed and at the encouragement of the State Land Board the State Highway Commission changed the name back to Lewis and Clark Cavern State Park. Currently the park is under Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

When the land acquisition program was finally accomplished Lewis and Clark Cavern State Park encompassed 2770 acres.

Bozeman to Lewis & Clark

Caverns (37 miles) - Jump on Interstate 90 and head west until you reach the exit for Highway 287. From there, head south to the Lewis & Clark Caverns.