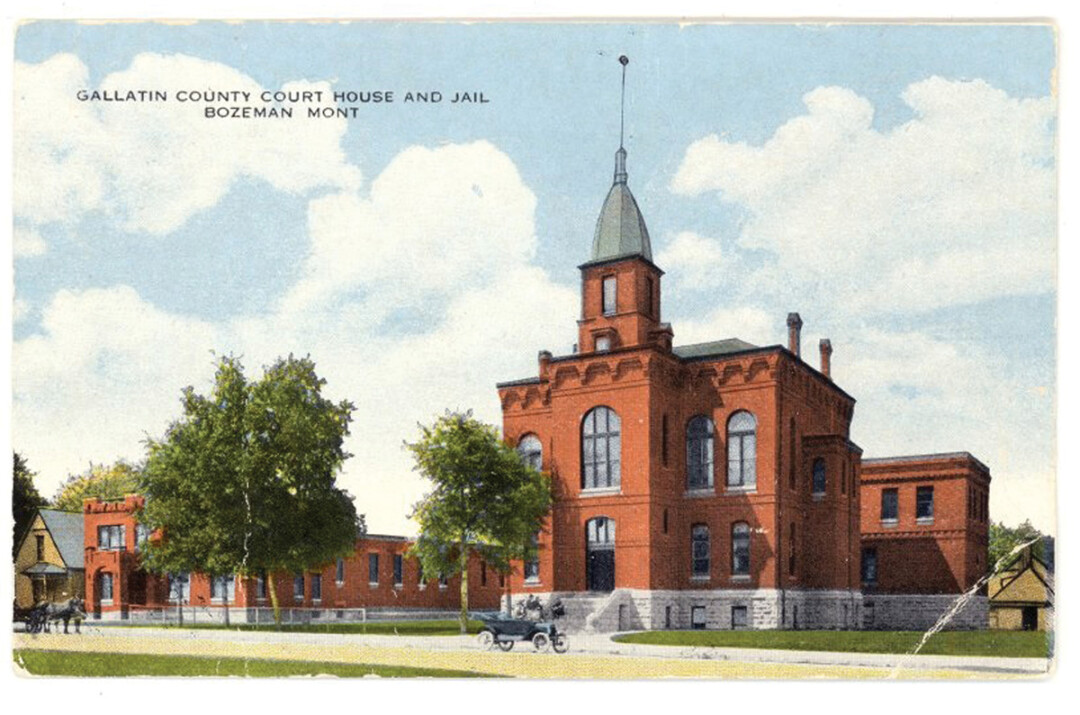

Escape From the Jail!

On the morning of December 22, 1911, all were surprised to find that six prisoners had escaped from the brand new $35,000 jail, which had been believed to be “escape proof.”

The individual cells holding the prisoners were not locked, an oversight by the department who believed the automatic locking front door to be adequate to hold the cell block.

The Tacoma Times (Tacoma, Washington) would print a small article titled “Watchman Proved Good Sleeper,” which was in fact, partially true. Jailer Horace Bull was in the building, asleep in an overhead room according to the Bozeman Evening Courier. According to the original blueprint, the jailer’s office was located on the main floor, just a short distance from the cells. In this room, he probably would have heard some sort of commotion. But the article states he was “overhead” which means that he either was asleep in one of the unfilled portions of the building (women’s cells, juvenile cells or the infirmary) or in the Sheriff’s bedroom, which would have been on the opposite side of a two-foot concrete wall, with little chance of hearing anything going on in the cell block. Clearly not an ideal situation for keeping watch over the prisoners, which goes to show the faith they had in the new locking mechanisms themselves.

It seems the prisoners had made a point of studying these mechanism’s as plumbers, painters and general workers came and went throughout the final stages of construction. In fact, the plumbers inadvertently had a helping hand in the escape by leaving a tool kit behind with just the right instruments for the job of releasing the catch on the only door that kept them from the guard’s corridor. As mentioned before, they were not locked into their individual cells.

The escape was far from over once access to the corridor was achieved. The group was still trapped in the cell block with locked doors on all sides of them. However, they had a brilliant plan and again fateful means of execution. The workers had also left behind a ladder. The prisoners climbed the grated cage of the bull pen and used the ladder to reach two small vent holes built into the North wall of the room. Ropes made from blankets tied together were used to lower themselves down into a narrow corridor. The corridor was part of the heating system for the building, allowing hot air pumped from the basement of the courthouse access to the new jail building. Beyond this corridor lay Siberia, or the Isolation Cells. By all accounts, the corridor was a dead end, but somehow the prisoners knew of the steam tunnel connecting the two buildings which they used as their main objective. It is possible that one of the prisoner’s experience as a boiler maker and machinist aided in the planning and execution of the escape.

At the east end of the corridor lay the tunnel, easily accessed with a raise of the grating covering the hole, which was about six feet deep. The tunnel itself was less than four feet tall, so the men had to crawl through it to the basement of the courthouse where they found themselves trapped at the foundation of the courthouse. Armed with tools, however, the group managed to chip away and dig through this foundation which led them into a little room below the treasurer’s vault. Pushing through another floor grating, the men found themselves in the vault, with no way of escape as the door was a locked iron barricade. Back in the room underneath, the group managed to break through another foundation wall which led them into the boiler room. Once here, escape was easily achieved, and the men simply walked out of the building and into the city. The Courier noted: “their tracks were plainly discernable in the snow this morning. They went to the corner of Mendenhall and Third and dispersed from there. It is believed some of them caught outgoing trains.”

Interestingly, there were other men locked into the Bull Pen that night, who did not have access to tools, and were separated from the men in the cell block. Whether those escaping offered assistance to those still trapped is unknown, but regardless it seems the detained did nothing to try and alert the jailer, remaining relatively quiet throughout the ordeal.

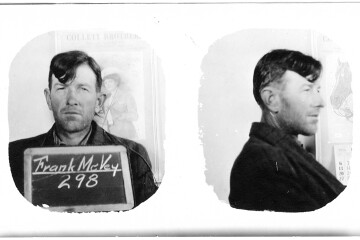

The escapees were named and charged (not necessarily as accomplices, but charged of similar crimes) : Fred Thompson and Ed. Sayers, assault to commit robbery, Frank Furlong and George McCarrick, box car robbery and Peter Mendeville and Joe Penna, burglary. It was noted that Thompson and Sayers were the “worst of the bunch” as they were the “thug type and dangerous.”

The following day the prisoners were still at large, although Sheriff Sales was quoted, “They may have gotten out of Gallatin County but they’ll be caught sooner or later. We are working quietly on some clues.” On January 1st, 1912, three of the men were caught, in Grand Island, Nebraska, nearly 1,000 miles from Bozeman. Sheriff Sales made the trip himself to bring them back. The week before, Fred Thompson had been caught in Forsyth and brought back to Bozeman. The following week Mendeville and Penna were still on the loose, but it was noted that the “dragnet is closing around them,” and they could be caught any day. However, the search was quickly dropped, and the men weren’t pursued in a “good riddance” gesture.

For decades, this story has been shared with visitors to the Gallatin History Museum, formerly the 1911 county jail. A tunnel runs from the jail to the current courthouse which is a delight to the many school children that tour the museum. The story was intertwined with this tunnel, which made perfect sense, until the 1911 article was read through and the original blueprint of the building was revisited. Suddenly the known tunnel didn’t make sense. The article mentioned a steam tunnel, and the blueprint had one noted, but at the Northeast end of the building, not the Southeast end. Then fate stepped in, just like it had for the escaping prisoners. During an exhibit change, a shelving unit was removed and a hollow space was discovered under a portion of the flooring. After cutting through a section of plywood, the original steam tunnel was uncovered, and the story slipped right into place.

A piece of plexi-glass was installed over the hole, so now visitors can read the story and look down into the dingy basement where the prisoners made their escape. Today a concrete wall barricades the entrance of the tunnel as it would have run under the sidewalk to the courthouse, so one must imagine the open hole the prisoners managed to crawl through. But the new wall does give one an idea of the material the prisoners had to dig through to make their escape.

This would be the first of many escapes, but certainly was the most embarrassing having occurred immediately after the opening of the state-of-the-art jail.

August 19, 1932, the Bozeman Courier reported the escape of J.H. Smith, who was being held on a robbery and assault charge along with three other men. Smith had been placed in the women’s cells so that no communication could be made between him and the others. Sometime during the night, Smith managed to cut though two of the bars that covered the upstairs window and lower himself down with a rope made from a torn shirt. The department believed an accomplice had been at hand to supply Smith with the necessary tools and whisk him away. Ironically, the east side window was in view of Main street and within the glare of a nearby lamppost. There were no further articles to give clues as to the outcome of his escape, but it is worth mentioning that his name is not found in the prisoner registry again following his escape, leading one to believe he was not caught. The next year, an Edward Wilcox tried to dig his way out with a screw driver, managing to remove one layer of brick before his attempt was discovered. This was the usual escape plan of prisoners, which seemed to be an unsuccessful endeavor.

With original blueprints, newspapers, and the building itself to speak, stories like these will continue to be rediscovered at the Gallatin History Museum!