The Black Lives Matter Movement As An Asian American

The issue of race in America is complex. Many communities of varying cultures exist together often without accepting one another in a meaningful way. Growing up in a multicultural home as a mixed-race child, I often felt as a cultural outsider to either half of me. Around my white friends and family, I was the minority and with other Asians, I was “too white” to really fit in.

I had two different sides of me that were never really brought together. I wasn’t allowed to learn Tagalog from my mother growing up, which caused me to miss out on a lot of Filipino culture and deeper relationships. Even today, my mother and I have a strained relationship because of the language barrier between us. The lack of that half of my culture was filled by the other half of my upbringing: a mostly white-washed experience in which I still wasn’t fully accepted because of my mixed origins. As a child, I was unable to understand where I stood amongst the white kids with “normal” upbringings. When I looked at myself, I couldn’t tell if I even looked Asian or not. I became used to random strangers asking questions like: “What are you?” “What’s your heritage?” “Where are you from? No, originally.” These questions solidified my racial ambiguity. I became used to identifying as white and American first before my more prominent Asian culture. The questioning reminded me that although I had embraced and assimilated into white culture, I was not white.

“The U.S. Asian population overall does well on measures of economic well-being compared with the U.S. population as a whole, but this varies widely among Asian subgroups. The median annual household income of households headed by Asian Americans is $73,060, compared with $53,600 among all U.S. households. But these overall figures hide differences among Asian origin groups.”

The above quote from the Pew Research Center partially dispels the stereotype of Asian prosperity in America. Despite it seeming positive, the stereotype speaks to the ways in which we profile races and assign generalized characteristics to them. Asian Americans have received a stereotype that may help them out in a business environment, but at the expense of generalizing an entire race of people under one aspect that isn’t entirely true. It’s a stereotype that we accept because it seems to benefit us, despite using racism to do so. Asian Americans of different origins struggle the same way that White Americans of different origins do.

Recently, I’ve realized how my racial identification has meant that I’ve felt justified in staying out of issues that affect other races. The overlying Asian culture of not speaking out or disagreeing with elders suppresses the opinions of younger generations. Traditional Asian culture teaches us to not speak out, that it is better to stay out of controversial things and not stir up unnecessary trouble. Obedience is an essential part of the culture and respect is demanded by older generations. When it comes to politics, I usually choose to stay out of things. I usually feel as though I don’t know enough or read enough in order to really speak on a topic. I make the excuse that politics upset me too much to warrant involving myself in them all the time.

The issue of systemic racism has transcended political leanings and is more important than my discomfort. The Death of George Floyd and many other Black Americans at the hands of the police is a wake-up call to anyone who could be profiled as “non-white.” There is a big difference in the way that people are viewed in this country on the basis of race, and racial profiling happens to almost every group seen as “non-white.” Just because it affects other POC (People of Color) differently doesn’t mean we should be silent about it. White is not “the norm” or “the default” and it shouldn’t be. The case to be made here is for equity and justice for all races. To be held accountable to the same degree in each and every circumstance. If there is inequality in a community, fix the inequality and do something about the people perpetuating it. The violence that happens to many people of color at the hands of the police is not justified, it is murder.

BLM (Black Lives Matter) doesn’t mean that other lives don’t matter; it just means that black lives matter too. It’s a movement meant to bring light to a history of black and brown lives mattering less than white lives. The focus is around equality, not superiority. This is a distinction I didn’t understand when BLM started in 2013. In fact, I was a supporter of All Lives Matter because I didn’t understand what BLM was really fighting for. At the time, most of the news media I consumed was exclusively conservative and anything outside that sphere was considered wrong. I was taught to hate left-wing media regardless of the message. I engaged with news and media without having the ability to consider it critically and accepting only one side of the story as truth. Any dissenting opinions were wrong, and I would have been seen as a traitor for expressing them. I felt like I didn’t know enough to question these sources and was afraid to speak up against voices seemingly more powerful than mine. Seeing only one approach to BLM kept me from considering the true meaning of the movement. I saw BLM as a movement seeking to divide us on the basis of race instead of unity.

The Civil Rights Act was signed in 1964

This is much more recent than we would like to acknowledge. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. died fighting for Civil Rights, and we have since accepted our country as non-racist by default. We assumed we had beaten racism for good. This lie was especially easy for me to believe growing up because I had never lived it or experienced it. I also benefit from being a woman and passing as white; both characteristics have given me privilege over other POC (People of Color). Though major progress was made during that movement, the fight against racism is far from over. Black people have to live in this country with the reality that they are still not treated equally. Those who continue to participate in and benefit from systemic racism get to feel like racism isn’t an issue anymore, but the reality is that the system is still inherently stacked against POC.

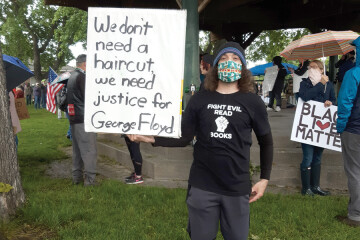

There have been two recent BLM protests in Bozeman: one on Sunday May 31st and another on Friday June 5th. Both were led by BIPoC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) and sponsored by The Montana Racial Equity Project and the Black Student Union at MSU. Attending the two protests sparked a lot of different emotions for me. I felt optimistic and empowered by the number of people coming together in solidarity against racism, both locally and nationally. It was encouraging seeing just how many non-black people showed up to stand next to black and brown people in our community. Although counter-protesters with guns were present, they were greatly outnumbered by BLM protesters.

The protests were peaceful and well-organized, following social-distancing and safety protocol to the best of its ability. Nearly all the protesters were wearing face coverings. There were also people trained in de-escalation procedures and people to hand out masks and water. I was proud of our community. It’s easy to decide not to act, to not show up to a fight that seemingly isn’t yours. Especially coming from a culture that tends to suppress its younger members, it was good to see some fellow Asian protesters speaking out against injustice.

Being an active ally for POC is difficult; it can be hard to know where to start, what to do. I have considered myself an ally of POC for several years without actually having taken action. To understand your role as an ally is to remember that not being racist is simply the baseline, but being anti-racist is where we should all strive to be. To be complacent is to perpetuate systemic racism, and in doing so you fail in your role as an ally of POC.

In order to make the change, you must educate yourself on the topic. In the interest of further education, I recommend a list of readings that address race relations directly:

How to Be an Anti-racist Ibram X. Kendi,

White Fragility Robin DiAngelo;

Me and White Supremacy Layla Saad;

So You Want to Talk About Race Iljeoma Oluo

It is difficult during times of tension to have conversations with friends and family. To make a change, you must be willing to be uncomfortable. Mistakes will be made, but effort has to be put in to make progress. Do not alienate or attack people. Be calm and factual in your assertions. If you meet resistance, do not be offended or defensive, take it as a chance to learn something new and help others do the same.

Ultimately, what’s going on right now isn’t about me. It’s about understanding the fear and frustration Black Americans feel on a daily basis. It’s about amplifying the needs and voices of those who are suffering. It’s about focusing energy towards the groups that need the most help right now. And as a non-black person, it means standing against injustice. This is our fight too.