The World Has Never Seen the Equal of This People

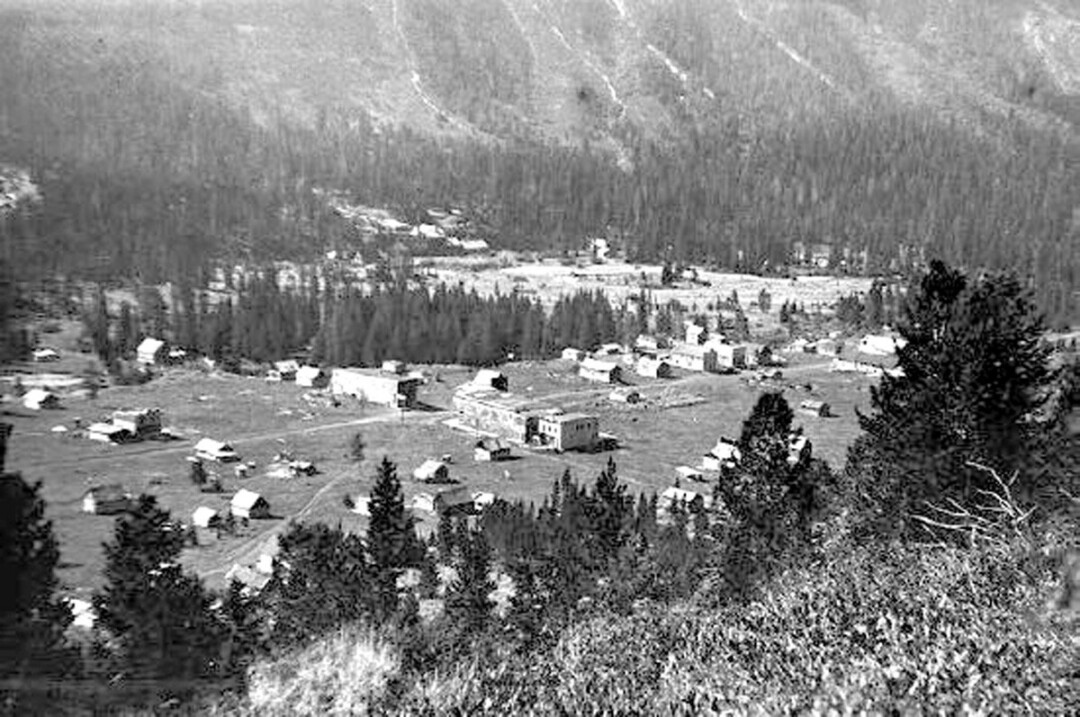

From 1870 to the 1930s, the town of Cooke City, lying just outside Yellowstone National Park at the Northeast Entrance, fought a long and hard battle for adequate transportation of its mining ore. The railroad never came, but the fighting spirit of these people still lives on.

As 1889 drew to a close, a new voice chimed into the railroad issue, that of Professor G.C. Swallow. Swallow spent two weeks in late September, early October of 1889 at the New World Mining district looking over the properties for his annual report as territorial mine inspector of Montana. It was said that “Mr. Swallow is favorably impressed with the extent and richness of the deposits of the New World district, and as his position as professor of mineralogy in the State University of Missouri, coupled with extensive practical experience in Montana, has rendered him proficient in mining matters, his favorable opinion will prove advantageous to the camp in bringing it to the attention of outside capitalists.” The Helena Independent Record printed the first of Swallow’s articles on October 29th. If Cooke City had ever wanted a spokesman, here he was, in lofty poetic prose, demonstrating the hardships of the miners and the steps that must be taken to rectify the situation. According to Swallow, the miners of Cooke City were akin to the great pioneers, pushing west, promoting industry in the wilderness, and there is little written that comes close to his descriptive analysis of them:

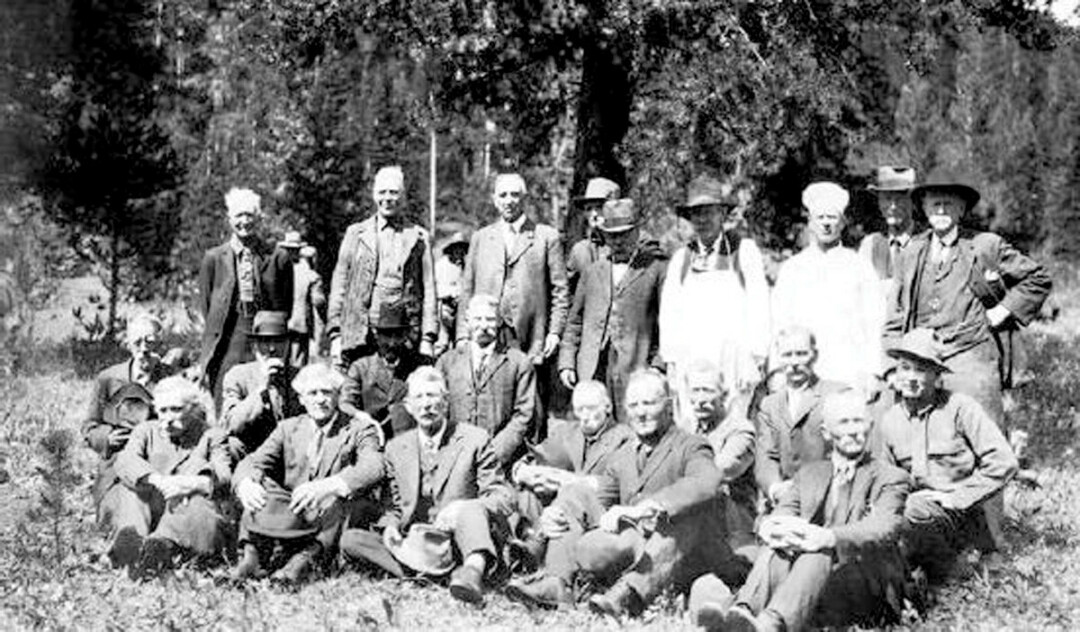

The people who discovered, developed and hold the mines of this district with a firm belief in their vast wealth, belong to that intelligent and vigorous and patriotic portion of Americans who have finished up the states of the Atlantic Slope, made those of the Mississippi Valley and are now laying broad and deep the foundations of the great commonwealths of the Pacific Slope and the Rocky Mountains. The world has never seen the equal of this people. Ten thousand times more efficient than an army with banners have been these bands of workingmen and working women, in their quiet but never wavering march from the Alleghenies to the Pacific, taking with them their household goods, their plows, their picks and shovels, their schools and their churches…behind it sprang up farms which feed the world, cities and railroads, what they call civilization: and from it poured out the streams of gold and silver and copper and lead which have vitalized and made permanent the financial condition of the country.

Such began Swallow’s plea for justice in the name of the miners of Cooke City, who belonged in the ranks of “men who have made the country.” Swallow had his audience hooked by those first paragraphs filled with adventure and a sense of destiny. What a better platform than to build a strategic discussion of the railroad issue, in particular the route through Yellowstone National Park. Swallow considered the objections to this route “more imaginary than real” and argued for Congress to make the Yellowstone River and Soda Butte Creek the Park boundary, thereby allowing a railway to be constructed on the north side. Swallow claimed that “such a natural boundary between the park and the lively, enterprising people of Montana” must be a well-defined line, otherwise “there will be endless disputes between the American citizen, who thinks his right to bear arms and shoot game should not be questioned and the American soldiers, who is detailed to keep the American citizens from shooting and killing game on the park.” A visible line like the waterway would be an unquestionable boundary between what was right and what was wrong; “no need of mistakes and contentions.”

Swallow went on to “answer” the arguments against the railroad and the claims that the symmetry and attractions of the Park would be destroyed should that portion of the land be surrendered to the public. As always, his responses contained lofty ideals, as in his answer to the symmetry of the current square boundary disturbed: “the proposed boundaries of the meandering streams must be more beautiful and pleasing to all lovers of natural objects in ‘Wonderland’ than the stiff, straight line now claimed.” In response to the attractions cut off, he centered his discussion around the Soda Butte Cone, making a sarcastic promise that no tourist would miss the opportunity of viewing it within the Park:

If this Soda Butte is insisted upon as a detriment to a railroad that will put millions and millions in the national treasury, Mr. Fitzgerald, of Gardiner will take the contract to move Soda Butte over the proposed line into the Park and thus save to the nation’s wonder seekers the inexpressible pleasure of seeing a butte about twenty-five feet high and twenty-five feet diameter of base, which was once deposited by a spring or geyser, now inactive, and which has lost all its attractions by the fact that its original cause has ceased to exist, that men, perhaps goats, have trampled over it till all the original and interesting features have been obliterated—the central vent filled up, and the side next the creek undermined and caved in—the whole will soon follow and there will be but little of Soda butte left for tourists.

Little did Swallow know that nearly 130 years later, the Soda Butte Cone would still be standing, an attraction for many a tourist visiting Lamar Valley. But putting the future aside, during his time Swallow would no doubt have influenced many a reader into rallying behind the noble efforts of the Cooke City miner and railroad engineer. On November 8, 1889, the next installment of Swallow’s analysis was published in the Helena Independent, his topic of discussion redirected from mining to forestation. The article was subtitled “Plenty of Water and Vast Areas Covered with Timber for the Mine and Smelter, While the Rest of Montana was Parched, Here were Gushing Streams, The Lesson to be Learned From the Destruction of Forests—How Nature’s Reservoirs are Preserved.” Swallow began his discussion stating, “One of the features of the New World district is its extensive dense forests of pine, fir and spruce, with here and there a patch of aspens, willows or alders…here we have a vast forest region covering an area of some 2,000 square miles, ample to furnish fuel and timber for the thousand mines which will be worked in this region.” He then went on to explain how the forests surrounding Cooke City not only provided needed fuel, but how in the autumn of 1889, “after the driest spring, summer and fall ever known in Montana, the mountains and valleys of this forest region were literally sparkling with cool springs and running streams.” He used this example to describe in three stages how the forests in the mountains helped to provide water for the lower plains, in scientific terms, before comparing the hillsides of industrious Helena with those of unspoiled Cooke City: “If one would see the difference let him visit Cook[e] City and feast his eyes with the glorious forests and the perennial fountains on every hill side and the sparkling streams in every ravine and valley, and then come back to Helena and see our mountains, once clothed with grand old forests and native reservoirs, but now hideous with blackened stumps and naked soils, dry gravels and pebbly channels, where, before the axe destroyed our forests and natural reservoirs, springs gushed and streams flowed to quench the thirst of the miner and wash his golden sands.”

His position on deforestation seems set, and yet his priority was still to see a railroad bring industry to Cooke City. His writing may be a forewarning on what could come to be if care was not taken on the onset to protect the vital resources the district had in its favor, or maybe he thought an environmental stance could silence the opposition held by the Forest and Stream editors. Regardless, his discussion had shifted dramatically from the railroad issue that Cooke continued to face. Part three of these published articles brought the focus back to the matter at hand: “It has been shown in these articles that there are at Cooke City and in its immediate neighborhood numerous mines which have yielded and will continue to yield vast quantities of the ores of gold, silver, lead, copper and iron, suitable for smelting… But there is one difficulty in the way of the profitable working of these mines---the great cost of transportation.” His argument again turned to the lure of adventure and the duty the American public owed the miner, willing to work the earth for the benefit of all: “The discoverers and owners of the Cook[e] City mines belong to the true pioneer class of Americans…[who work] in the face of the most daring hostile tribes, thousands of miles away from the nearest supplies of food and clothing and mining implements and the protection they might need from their government.” The danger did not lie exclusively in physical harm; these pioneer miners and associates had “worked our mines” and made “expensive experiments with furnaces and mills,” and had done so “when the freight was more than the original cost” all in an effort to learn the best method by which to work the mines. According to Swallow, “These pioneer miners and their helpers, full of enterprise and manhood, and quick to learn, are now masters of the situation at Cooke City” and “believe in their mines and are determined to hold them and wait for the railroads, which alone can give them cheap transportation and make their smelting ores profitable.” Swallow summed up their situation as such: “These men have worked out hundreds of tons of gold and silver bullion, but so diluted with lead that the freights exhausted all the profits of working.” But he held hope for the camp, a hope that lay in the development of a railroad:

When Cooke City has a railroad which will furnish cheap freights she will furnish the bullion to keep trains in constant motion on to eastern markets for the next hundred years. These idle mines and cold furnaces will be aglow with vital energy. A thousand miners will take the ore from a hundred mines, and the furnaces will pour out glowing streams of golden bullion.

Following this persuasively positive review of the miners, Swallow went on to suggest a plan for the railroad, listing those “wonders” that would or would not be lost should the route of travel be altered. At the end of the list, he concluded that the “grand old mountains will probably stay even should the railroad pass up this valley [Lamar] and give thousands more the privilege of seeing them and the rich mines whose ores will yield golden streams of the precious metals to freight the road and enrich the world.” His final words were a plea for action: “How then can a congressman refrain from so changing the boundaries of the National Park as to let the railroad pass up the Yellowstone and Soda Butte to the great mining camp of Cooke City.” This last article was published in the Holiday edition of the Livingston Enterprise on December 25, 1889. Despite Swallow’s pleading pen, the railroad would not be persuaded to come to Cooke City.