Bozeman’s Historic African American Community

At the time of Bozeman’s founding in 1864, the United States was in the throes of the Civil War. Due to the war and the discovery of gold, people were fleeing the States and looking for refuge and fortune in the Territories, including Montana Territory. People of African American descent were especially motivated to leave the States, fleeing enslavement and brutality. They came to Montana Territory hoping for something better. Two of many African American families to find a home in Bozeman were the McDonalds and the Andersons.

By 1870, Bozeman’s population was incredibly diverse, including those who came here from the Northern and Southern United States, from Western and Eastern European countries, and from Asia. If you walked down the streets of Bozeman in 1870, you would hear many English dialects, but also a variety of different languages being spoken. Historically, Bozeman’s Black community was not as large as Helena’s, Butte’s, or Great Falls,’ but the community was close-knit nonetheless. In 1870, the census shows there were eleven members of the Black community. In 1880, there were twenty-three (the entire population of Bozeman being 894). In 1900, thirty-three Black residents lived in Bozeman (out of 3,419), and in 1910 there were thirty-seven (out of 5,187). In 1920, the Black community peaked at forty-one (out of 6,183), and then began to decline. In 1930 there were nineteen Black residents, and by 1940 there were 21 (out of 8,665). Members of Bozeman’s historic Black community settled in the area for reasons that mirrored their contemporaries. They were interested in good jobs and the ability to purchase land and build a life.

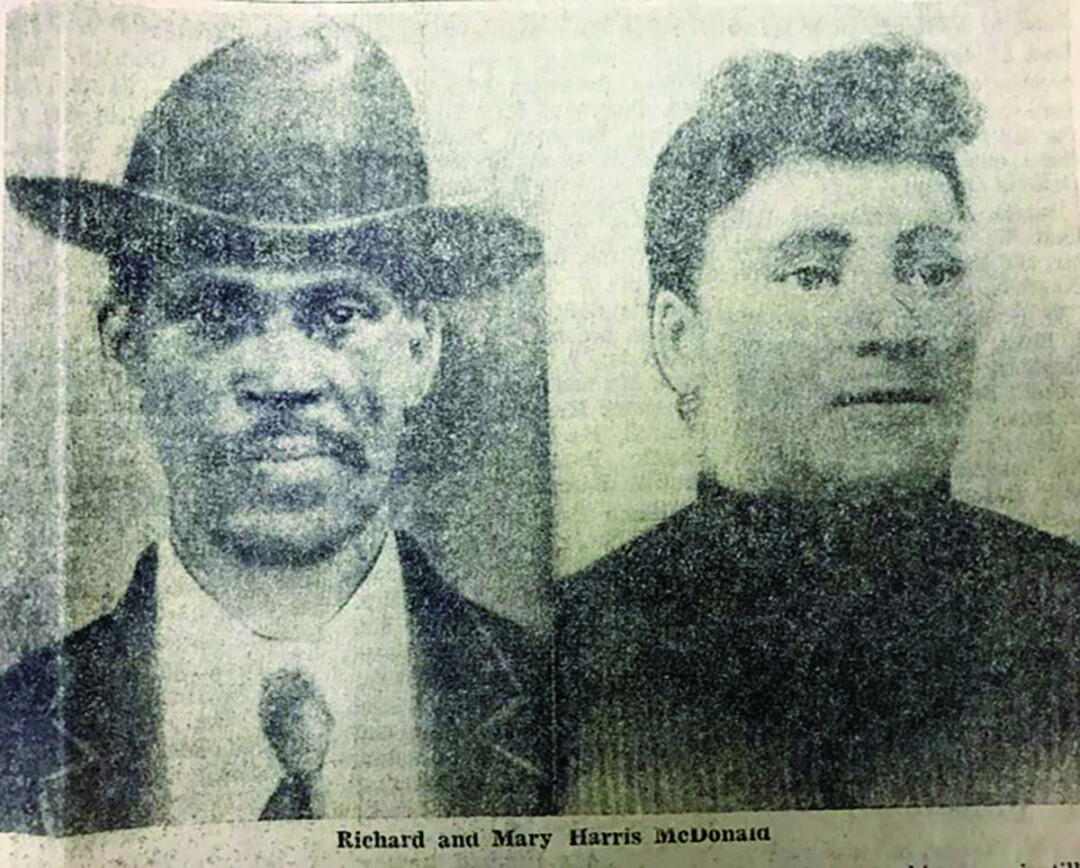

The McDonald family was the first African American family to settle in Bozeman. Richard and Mary McDonald both grew up enslaved in Missouri. They married around 1861, were emancipated, and left St. Joseph, Missouri in 1864 for Montana Territory. They traveled overland with a wagon and six oxen. They first went to Virginia City, as most did, but realized it was too “wild and woolly” for them, so they settled in Bozeman in the fall of 1864. They built a small cabin on what is now south Tracy Avenue, and Richard began freighting goods between Bozeman and Virginia City, and later, between Butte, Billings and Fort Benton. They soon built additions onto their small cabin, and eventually a second story. Their house still stands at 308 South Tracy Avenue. Mary and Richard brought a six-month-old son with them when traveling overland but, like many children on the trail, he died and was buried along the way. After settling in Bozeman, Mary and Richard had three daughters and three more sons. The three sons all died young. The three daughters survived frontier sicknesses, all living to adulthood. Richard died in 1898 at 65 years old. Mary lived a very long life, dying in 1941 at the age of 100. The three daughters of Richard and Mary, Mollie, Belle and Melissa, all lived long lives in Bozeman. Mollie married Charles Ward in 1900 and they had two children, Richard Jr. and Belle.

Richard Jr.’s story is a sad one. In 1920, Richard, Jr. found himself in a dispute with Fred Rogers, another member of Bozeman’s Black community, and ended up shooting and killing him over $3.60. Richard Jr. went to jail and died imprisoned at the age of 36, from tuberculosis. He was allowed to come home to his grandmother’s house at 308 S. Tracy for his final days. Belle lived for many years in the family house and died in the year 2000. She was the last of the McDonald line in Bozeman.

The McDonald sisters left a legacy in Bozeman. They were involved in church and civic groups, including the Montana Federation of Negro Women’s Club, a state-wide organization that promoted and encouraged its members to better themselves and their families. In 1921, the three sisters founded a local chapter of the Montana Federation, which they called the Sweet Pea Study Group.

Another Black family of note in Bozeman was the Andersons. According to the 1900 census, John Anderson had been born near present-day Oklahoma City in Indian Territory in May of 1833. His parents were enslaved by Lewis Hildebrand, a member of the Cherokee Nation. Anderson himself grew up enslaved and was of African American and Cherokee descent. Anderson recounted his early life to Reverend John Adams of Butte in 1914, saying; “I lived in Oklahoma near the scene of my birth til the war broke out in 1861 and then I ran away. I remember the incident as if it were yesterday. It was on the 15th of March that two Yankee spies came to the log hut where I was quartered and asked me to hide them over night. I did so. The next morning they arose early and on leaving, carried me to the brow of a little hill just over a spring near the old ‘big house’ on our plantation.

They showed me the camp where the federal troops were stationed and told me that if I wanted to get away I could find protection there. This camp was about 32 miles from Fort Scott, Kansas. A little after these soldiers left, I shadowed them to the camp and went straight to the officers’ tent; sure enough, just as they had told me, the officer took me in. I got work cooking for Captain Greenough and Lieutenant Phillips. I cooked for them till April, 1862, when I went to Fort Scott and enlisted in the army. My enlistment was in Company A, First Kansas Colored Infantry. I staid [sic] in the army till 1865, at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. I am sure I am not mistaken when I say during that time I was in 23 battles.”

Anderson left his service with a disability, a gunshot wound in his right lung. Soon after mustering out of the Army, Anderson traveled west with a small group, arriving in Virginia City, Montana Territory in December of 1865. He lived in Virginia City, marrying Julia Williams, and the couple had a child while in residence there. By 1867 Anderson was living in Helena, where his marriage to Julia dissolved. John married a second time in 1870, to a woman by the name of Lucy. The couple moved to Bozeman in 1872.

Bozeman was a small town, and with the goldfields playing out and the Panic of 1873, there was much concern for its financial viability. Bozeman residents began looking for additional avenues of income for their small town. In this vein, a group called the Yellowstone Wagon Road and Prospecting Expedition formed in 1874. The stated goal of this expedition was to locate a wagon road and prospect for gold. The expedition did not achieve these goals, but instead created additional hostility with the Lakota Nation – which may have been the unstated but true goal of the expedition. John Anderson was a member of the expedition, serving as cook. He was heavily engaged in the battles fought between the expedition members and the Lakota. Upon his return to Bozeman, he claimed to have killed Sitting Bull’s son during one of the battles. True or not, Anderson was honored for his bravery in 1895, and made a member of the of the Gallatin Pioneer Society.

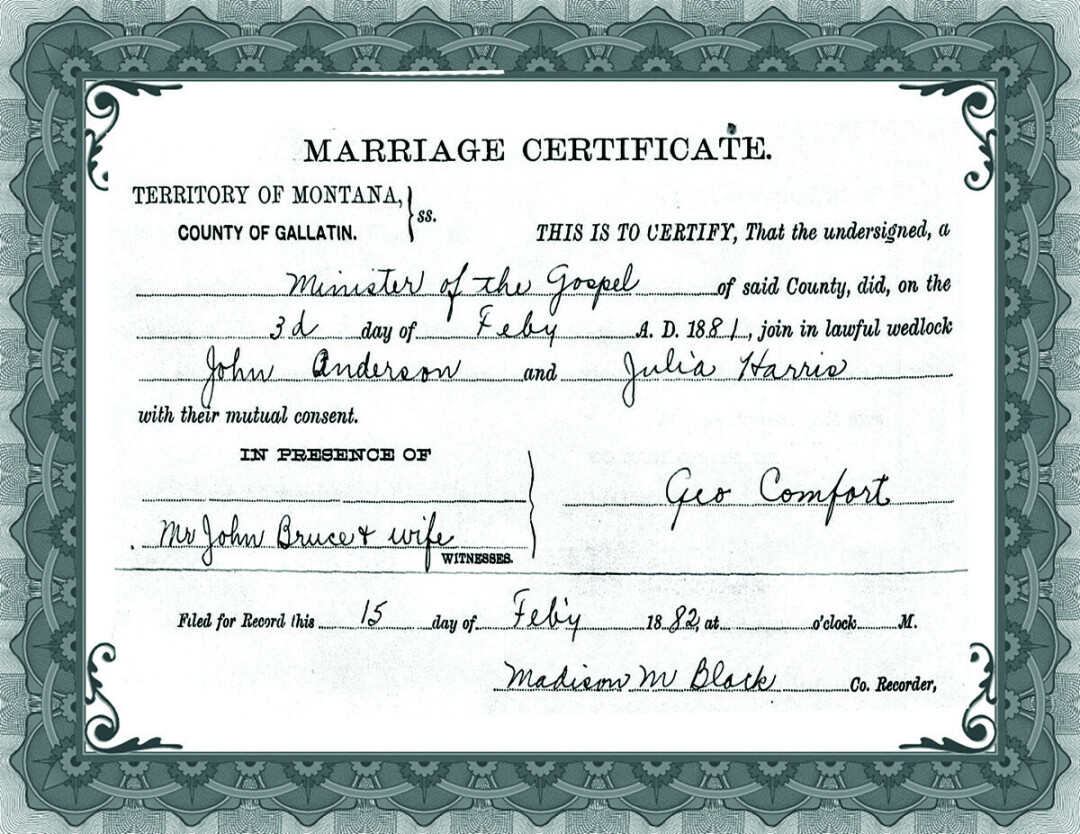

John’s marriage to Lucy ended and, in 1881, John married a second Julia, Julia Harris. John worked many jobs while living in Bozeman, including as janitor for the Bozeman Elks Lodge, and as janitor and engineer for the Bozeman Carnegie Library.

Julia Harris’s story is much harder to tell. She was born in Kentucky in c.1839 and grew up enslaved by a cousin of President Abraham Lincoln’s. This man owned 456 people, 200 of whom joined the Union army to fight for their freedom during the Civil War. It is unknown how or why Julia Harris came to Bozeman, but she was here by about 1870. She married John Anderson on February 3, 1881, when she was roughly 42 years old.

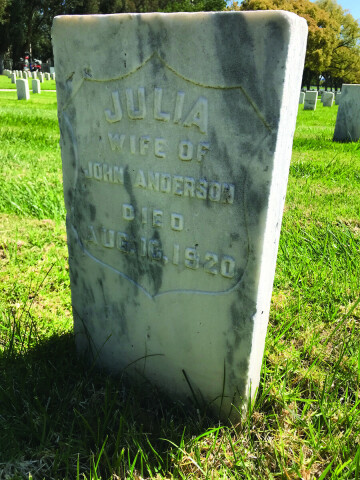

As age crept up on John and Julia, they realized the need for greater care, so they moved to a soldier’s home in Sawtelle, California in 1918. Julia died in 1920 and John in 1925. They are buried side by side in the Veterans Cemetery in the Los Angeles National Cemetery in Los Angeles, California.

This is a story of just two significant Black families in Bozeman, the McDonalds and the Andersons. There are many more members of Bozeman’s historic Black community, with stories of refuge and contributions to our community. Their stories have been lost to time, but we can piece them back together and include them in our historical narrative. As we look to the future of our community, let’s hope we come back to that time of diversity and welcome more people of color into our town. There is hope, as last month we welcomed our first Black City Commissioner, Chris Coburn, a sign of good things to come for our community and its legacy of early historic diversity.