Observing Nature with the Montana Master Naturalist Program

"Hey dolla dolla bill, y’all!,” I say melodically, then laugh. My attempt at a birdsong mnemonic for the white-crowned sparrow isn’t quite accurate, but it’s always fun to say.

I learned how to create these memory-jogging catch phrases during a Montana Master Naturalist course I took last year. This particular mnemonic not only helps me identify a specific birdsong, it also reminds me of a beautiful day hiking around a post-burn area in Paradise Valley. Singing my “dolla bill” ditty brings back memories of twitching tent caterpillars, a clear creek roaring in its bed, taking notes in my nature journal, a peanut butter sandwich eaten in the shade of an aspen grove, and a whole lot of laughing about how often the group stopped to investigate things we found along the trail. The song has become more than an auditory tool—it’s a detailed snapshot in time that evokes an entire sensory experience. It was raining when I sat down with Cedar Mathers-Winn to talk about the Master Naturalist program. He teaches the certification course here in Bozeman twice a year through the Montana Outdoor Science School (MOSS), and was my instructor last summer. Between bites of homemade cherry pie, we traded thoughts on how the course provides the basic background and framework for understanding general ecology and taxonomy, while leaving space for students to explore what they find interesting.

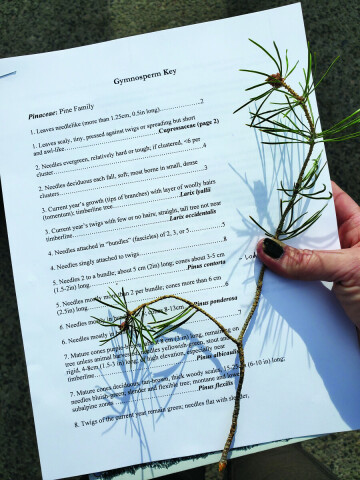

Sparking curiosity and excitement for the natural world is one of the best ways to promote environmental stewardship, and is a primary goal of the program. Diverse groups of people taking the course come together to increase their knowledge of natural history and build community through volunteerism. It’s also an opportunity to build a deeper sense of place, using nature as a classroom. Inquiry-based learning grounded in local contexts is both relevant and engaging. Some of the best parts of the Master Naturalist course were the outdoor field lessons: armed with identification keys, field guides, and bug nets, my course-mates and I were fully immersed in the habitats we were studying. These sessions helped us develop a better awareness of how individual components of an ecosystem are interconnected by seeing them first-hand.

Late last May, I met my fellow course-mates for the first time under a large willow tree at the fish hatchery east of town. We sat in a circle and shared our names, and our reasons for taking the course. After we introduced ourselves, Cedar asked us what we hoped to learn over the next nine weeks. One person was interested in mushroom foraging, and another wanted to improve their tree identification skills. Several of us were excited about birds and wildflowers. I remember Cedar grinning as we made a list; it was obvious that he was just as excited to be there as the rest of us.

Cedar’s passion for natural history is infectious. In his company, a short walk outside becomes an eye-opening dive into ecology at the local level. He notices things that most people pass by. “Observation is the backbone of nature study,” he says, “and if you watch long enough, you’ll always find something amazing.” He emphasizes that the slower you go, the more you discover. That’s quite the challenge to those of us caught in the web of “busy culture,” but taking a moment to lift a rock to see what’s underneath, or stopping to listen to an interesting bird call can change your perspective and how you interact with your home place.

As we sat under the covered porch listening to a concert of rain and birdsong, Cedar reminisced about some of his field jobs studying birds all over the world. He laughed as he recalled sneaking around Dominican Republic rainforests with a microphone, waiting for birds to vocalize; he would get up at 3am to get recordings before clocking in for the day. The birds were always on their own schedules though, and Cedar tells a story about a time in Australia when a little friarbird perched on top of his tent, serenading all with its persistent song. The image of Cedar crouched in his tent with a microphone held up in the air makes me chuckle as I type.

Cedar has always “followed the sound.” His musical background opened his ears to the world’s sounds, and an interest in natural history followed. The variety of sounds that birds make were fascinating to him so, after completing an undergraduate degree in music, he went on to work in the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. He then pursued a Master of Science degree from the University of Montana, specializing in bird communication, and now teaches the observation skills he honed during his field biologist days to groups of engaged citizens in the Montana Master Naturalist program.

Gathering information by observing nature used to be essential for our survival, but today we have the luxury of observing nature for our own purposes. Spending time outdoors improves our quality of life. When we slow down and take the time to notice what’s around us, we begin to build an intimate relationship with nature. Our innate human curiosity inevitably leads us to ask questions; as we seek answers to those questions, we discover that the Earth is more vast, complex, and intricate than we could ever have imagined.

As lifelong students of natural history, naturalists depend on all of their senses to interpret the world around them, from the smell of a fragrant flower to the feel of rough bark, the taste of an edible plant, the glimpse of a stealthy critter moving in tall grass, or the melodic call of an unfamiliar bird’s song. Master Naturalist course participants learn to keep detailed notes of these sensory experiences in a nature journal. I treasure the notes I took last year—in addition to excited scribbles about new plant and animal species, lists of rock-type characteristics, and local weather details, there are funny quotes from my course-mates, childish sketches, and book suggestions. It’s fun to read over them and remember how even the smallest sighting could send the group into a field guide frenzy.

It was still raining as I bid Cedar and his family goodbye and walked down the driveway singing, “hey dolla dolla bill y’all!” to the birds watching from their sheltered branches. The Master Naturalist course changed the way I interact with nature, helping me learn what to look for, and giving me the tools to understand what I’m seeing. Anyone with an interest in natural history, local flora and fauna, or regional ecology in general can benefit from taking the course.

So, consider this a reminder to slow down and appreciate being in the present. Sit in one place, watch, and wait. You can never be bored outside if you’re paying attention!

Become a certified Montana Master Naturalist through the Montana Outdoor Science School and the Montana Natural History Center! Class begins Thursday, August 18 and ends Saturday, October 15, 2022.Visit www.outdoorscience.org/naturalist for more information.