Promote Global Worming

I was in middle school when my family first set out for the Len Foote Hike Inn in North Georgia. Located just off the Appalachian Trail, this backcountry lodge holds a special place in my memory. The unassuming grey buildings on stilts, connected by walkways and surrounded by the lush vegetation of the Appalachian foothills, are just a five-mile hike from the trailhead, but the experiences I had there have followed me all over the country.

Upon arriving at the Hike Inn, a young woman with brown hair and a big smile greeted us. She proceeded to tell us some things we needed to know about our stay: details of our accommodations, when dinner would be served, and that there were plenty of games in the Sunrise Room overlooking the mountains. We were all excited to explore the grounds, but I had a question. Why was she wearing a t-shirt that said, “We’ve Got Worms”?

In answer to my question, she laughed and spun around so I could see the back of the shirt. In the same red letters as the declaration on the front, the words across her shoulders exclaimed, “Promote Global Worming!” above the name of the Hike Inn. I thought the shirt was great, but I still had no idea what it meant. The young woman explained that the Hike Inn practiced vermiculture. “It’s composting with worms,” she said, and offered to give us a tour of the vermicomposting bins after dinner.

Meals are family-style at the Hike Inn, and no one goes hungry. Leftovers are stored in a refrigerator for guests to eat later, or for A.T. thru-hikers needing a snack or meal. Spoiled food does not leave the Inn in a garbage bag. Instead, it goes into bins filled with red wiggler worms. The worms turn the organic food waste into valuable organic fertilizer to be used in the Inn’s garden. That explained the “We’ve Got Worms” t-shirt!

My family and I also learned that red wriggler worms can eat half their body weight a day in organic material. Some of the things they can eat are surprising, like feathers, dryer lint, and natural fibers. Our tour guide told us the staff had once experimented with an old pair of cotton pants—they ate every bit!

Earthworms are amazing creatures. These terrestrial invertebrates play the critical role of ecosystem decomposers, which means that they break down and recycle organic matter from dead animals and plants (as well as food waste from kitchens) and return it to the soil. Earthworms don’t have teeth, so they depend on an important body part called a gizzard to grind food down into smaller parts. After the organic matter has passed through the worm’s gizzard, it travels through the intestine, where nutrients are absorbed, just like in humans. Undigested material is then excreted as worm castings. Any good gardener can tell you how important worm castings are to a garden. Castings are full of nutrients, kind of like multivitamins for your plants.

The typical earthworms you’ll find in your home garden are commonly known as night crawlers (Lumbricus terrestris). However, these are not the type of worms you’ll find at the Hike Inn. Vermicomposting depends on the hard work of the red wiggler worm (Eisenia fetida). These resilient worms are rarely found in soil; they evolved to thrive in rotting organic material, making them perfect for adding to your compost pile or worm bin. They work at a rapid pace, but it can still take a couple of months for the worms to produce usable compost.

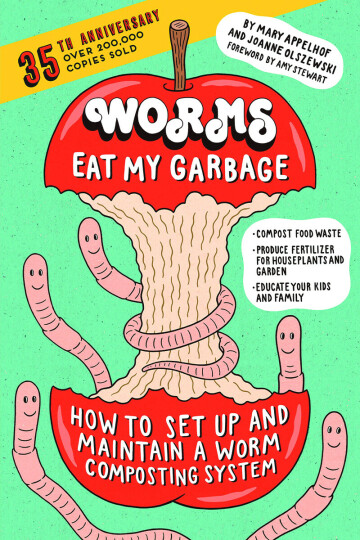

If you’re just as intrigued as I was when I first learned about vermicomposting and are interested in learning more about the process, there are many resources out there to help you get started. First, pick up a copy of Mary Appelhof’s book, Worms Eat My Garbage, widely regarded as standard reading in the vermicomposting world. Appelhof wanted to change the way people think about garbage, and she uses the book to share her knowledge with the world.

From here, you can buy a worm bin (or make your own) and some worms to compost at home. It can be a time-consuming process and will take some trial and error, but is an incredible way to learn about environmental responsibility and natural science at the same time.

If you’re like me, a renter who is always on the go, you can contact one of the vermicomposting companies in town. They will provide you with a five-gallon bucket and schedule a weekly pickup date. All you have to do is put your acceptable food waste in the bucket and set it out on your curb. You won’t get to personally witness the worms’ magic if you hand off your food waste, but it’s still an important step in keeping organic material out of landfills. Did you know that each year, over 55 million tons of food waste are sent to landfills in North America alone? For comparison, one male bison weighs around a ton (2,000 pounds), so that would be the entire estimated population of bison before the mid-1800s!

As I think back on my introduction to vermicomposting, I find myself daydreaming about beautiful gardens, fragrant soil, and summer sunshine. I think about hunting for night crawlers in my great-grandparents’ front yard in South Georgia, rescuing worms stranded on my driveway after the first spring rain, and admiring those red wigglers in the bins at the Len Foote Hike Inn.

Before my family began the hike back to the trailhead, I asked the young woman at the Hike Inn if there were any more “We’ve Got Worms” t-shirts. She sadly said no, and, to my surprise, gave me hers. It’s been almost 25 years, and while I don’t remember her name, I will always remember her generosity and kindness towards the curious teenager I once was. I still have the t-shirt and I often dream of going back to the Inn to teach educational programs to other visitors. Who knows, maybe they would even let me lead a worm bin tour.