MSU Bozeman The Early Days

Montana State University is an integral part of Bozeman. Our largest employer, it’s our claim to fame (think NASA and robotics research), and a source of pride with regard to sports, academics, diversity, and alternative energy, among other accolades. And, as MSU President Waded Cruzado rarely neglects to mention, it is a land grant institution. That is where MSU’s story begins, and what drives it to this day. In 1862, the U.S. Congress passed the Morrill Land Grant Act, an effort supported by the Republican-led Congress to create higher educational opportunities in agriculture and the mechanical arts, as well as for military training. The latter item was added in response to northern losses early in the Civil War. This movement, brought forward by Justin A. Morrill of Vermont, strove to elevate public education — and the funding thereof — to the higher levels enjoyed by enjoyed by railroad moguls and the mentally handicapped. The bill simultaneously offered education to the shrinking agrarian class and the growing industrial class, representing the struggle present in most states and territories. Montana is an excellent example of the yin-yang of these nearly opposite economic directions, which are also symbiotic. The result? Establishment of the Montana College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts on February 16, 1893, four days after the state legislature established the university campus in Missoula. The healthy rivalry likely began that week.

The glorious day of the birth as a university town came after Bozeman placed fourth in the 1892 race to become the new (as of 1889) state of Montana’s capital city. Among the many plums issued by the state legislature, the agriculture and mechanics college was given to Bozeman, and the state university to Missoula, as each city had lobbied for. These runners-up gifts were not easily come by during the nascent period of Montana’s statehood. In the book, In the People’s Interest: A Centennial History of Montana State University, the authors deftly and clearly describe the bantering and bargaining associated with the wins, attributing Bozeman’s success “in no small measure to the political acumen of Bozeman’s political and civic leaders, who formed a coalition of interests within a broader network of empire builders.”

Before progressing further, let’s get the names straight. What we now know as MSU in Bozeman was the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts from 1893 to 1921, Montana State College from 1921 to 1965, and Montana State University from 1965 to the present. What we now know as the University of Montana in Missoula was the University of Montana from 1893 to 1945, Montana State University from 1945 to 1965, and the University of Montana from 1965 to the present. The 1965 transfer of the MSU moniker from Missoula to Bozeman necessitates watchfulness when reviewing historic documents and newspaper accounts. For ease in this read, MSU will be used to indicate our Bozeman campus.

MSU’s grounds, expanse, and buildings reflect the organization, areas of study, and evolution of the school. MSU first operated out of temporary quarters downtown, while incrementally building a campus on the elevated land of the Capital Hill Addition (platted as part of the capital bid). In 1894, MSU opened its first dedicated building — the agricultural experiment station, with offices and classrooms. When Main Hall opened in 1898, its classrooms and office space were able to fill the school’s needs for its 60+ students. These two buildings, now known as Taylor Hall and Montana Hall, are what remain today of the promising origins. Montana Hall remains as the iconic, center hearth of our very full campus.

The 1904 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows both Taylor and Montana Halls, the duck pond, and the other utilitarian buildings that supported the campus. Greater regularity had appeared with the construction of the Chemistry and Gymnasium buildings, in 1898 and 1897 respectively, located in westward alignment with the Main Building. Even with the newfound stature and prominence of the two- and three-story masonry buildings, MSU’s rural and practical focus was clear in the Sanborn maps and early photographs, as was its isolation south of the city. The agricultural experimental station was immediately west of Taylor Hall, where it grew to support the extension’s training efforts across the state. The 1912 Sanborn map demonstrates steady growth of the campus in a short period. The practical improvements included the 1907-09 construction of the New Agricultural Hall (now Linfield) with a sizable greenhouse, the 1910 girl’s dormitory east of Montana Hall (now Hamilton Hall), addition of a greenhouse that doubled the footprint of Taylor Hall, additions to the gymnasium and the Blacksmith/Carpenter Shop, and construction of a large C-shaped dairy barn that anchored the experiment station complex. This dairy barn housed the Museum (of the Rockies) from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s.

MSU’s handsome campus conveys this rich story of hopes and dreams — of our country, our state, and of the thousands of individuals who have studied and worked there. What we see today contains a vestige of its early presence, with Taylor and Montana Halls establishing our perception (with the exception of Linfield and Hamilton Halls, the rest of the buildings depicted in 1912 are long gone). Many subsequent alterations are associated with the increase in enrollment and academic departments, which has remained steady, and sometimes seemingly explosive. In order to manage this expansion in a more formal fashion, in 1917 MSU adopted a master plan developed by Montana architect George Carsley and nationally known architect Cass Gilbert. This plan featured a long and wide east-west green space flanked by existing buildings Montana Hall and Hamilton Dormitory on the north, and placeholders for Physics, Chemistry, the Library, and Engineering buildings on the south. The Biology Building was assigned to a site west of Montana Hall. The western terminus of this classroom district was to be defined with an auditorium building, beyond which the barns and farm buildings were arranged symmetrically. The original agricultural building (Taylor Hall) would be removed to avoid asymmetry.

While the gist of the plan was generally followed, Taylor Hall remained, and construction of a large reflecting pool behind Montana Hall, and the library immediately south, was never implemented. The shifting of the library east opened a long viewshed and greensward between Montana Hall and Romney Gym (1922) at the south end of campus. The auditorium building was also never built per this plan, allowing the open avenue to serve automobile traffic (as Garfield Street), until converted into the pedestrian pathway Malone Centennial Mall in 1993.

The 1920s represented a huge growth period for MSU, funded by the post-war boom in the economy and a resultant generous legislature (to all of Montana’s schools of higher education). The expansion of MSU’s campus, increase of more than 150% in classroom space, and architectural compatibility between the buildings and the 1917 campus plan helped seal MSU’s reputation as a place for serious study.

As stated in Jessie Nunn’s 2013 nomination identifying the core of MSU as a National Register Historic District, “the favored style of the 1917 Carsley / Gilbert Campus Plan — Italian Renaissance Revival — dominated campus construction during the building boom of the 1920s. Six [of an original seven] Revivalist Style buildings (approximately 43% of historic buildings within the MSU Historic District) remain on campus today.” This stylistic consistency contrasted with the University’s eclectic architectural expression, prevalent prior to World War I. The six buildings noted in the National Register nomination create a warm, solid uniformity across campus, with colorful tapestry brick walls, stone bases, tile and terra cotta detailing, and clay tile roofing. Constructed between 1919 and 1926, the buildings are generally located where placed on the 1917 plan. We now know them as Traphagen Hall (Chemistry, 1919), Roberts Hall (Engineering, 1922), Lewis Hall (Biology, 1922), Romney Gym (1922), the Heating Plant (1922), and Herrick Hall (1926). The Heating Plant was placed in an area southeast of the campus core. The Engineering Shops, later known as Ryon Labs, was the seventh building in this grouping. Built in 1922 and located on Grant Street just north of the Heating Plant, Ryon Labs was demolished in 1995 to make way for the EPS Building (Barnard Hall).

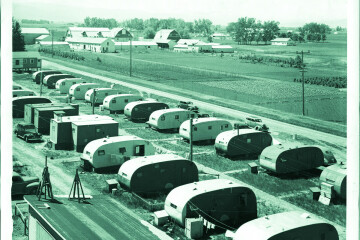

The improvements associated with the 1920s were not just relegated to construction, but the construction is certainly a reflection of MSU’s improved academic vigor. Strong programs had been developed in the sciences — chemistry, biology, engineering, and agriculture. The number of students (approximately 1,200) attending MSU in the 1920s rose during the Depression but took a dip during World War II, after which it surged with a vengeance. The heady period of Roland Renne’s presidency, from 1943 to 1964, helped MSU weather the storm of steadily increasing student enrollment from 1,155 to 5,250, particularly of women. Renne responded to the need for rapid expansion of classroom and laboratory space, residence halls, and academic programming. This boom period and the years leading to it will be addressed in a future article.