Lewis and Clark’s Encounters With the “Turrible” White Bear

The Missouri River, viewed by The Corps of Discovery as their flotilla entered Montana on April 27, 1805, was truly pristine and colorful, a great snag-toothed, twisting ribbon of water running free and wild as it surged through game-rich, verdant bottomlands. The Missouri region during this timeframe was one of the richest ecosystems on earth, with a big game abundance of staggering proportions, which made it the American equivalent of East Africa’s Serengeti. From any viewing quarter, the upper Missouri country occupied center stage, fixing attention with that mysterious magnetic attraction that can always be felt but never fully explained, that sure quality of wildness. Imaginations and expectations among expedition members at this point in their journey undoubtedly ran at high pitch as to what might be awaiting them around the next river bend. They would not be disappointed, especially in encounters with the largest and most feared of North American predators.

Our first reliable recorded information on the grizzly bear in Montana comes from Lewis’ active pen as he tells of a superbly designed, high-shouldered quadruped possessing unpredictable vagaries, seasoned with a testy disposition, whose authority was absolute in asserting its continental supremacy. After crossing into Montana, the party frequently observed grizzlies between the mouth of the Yellowstone and the Great Falls of the Missouri. By the time they reached White Bear Island at the mouth of the Sun River, nearly every member of the expedition could boast of being chased by a uniquely designed mauling machine that was more than capable of killing men who dared to encroach into its terrain. Grizzles were so numerous and aggressive at the Falls area that bear alertness became a preoccupation.

The captains ordered the men to sleep with their guns close at hand, and forbade them to venture alone along the river. Lewis’s Newfoundland dog, Seaman, did his part by barking whenever a bear came near camp. The Lewis and Clark journals document 103 separate grizzly encounters. Of this total, 88 were in Montana, including 12 wounded bears, and 28 hunter kills.

Lewis tended to discount earlier Mandan Indians’ cautionary warnings about the ferocious “white bear” as grossly exaggerated. The grizzly encounter in the vicinity of Montana’s Valley County on May 11, 1805 gave Lewis sufficient pause on the disposition and ferocity of the “turrible” bear. Lewis reports that the explorers were surprised at the sight of Private Bratton running toward them, frightened, and hollering. Gasping for breath, he mentioned meeting a grizzly bear, which chased him about a half mile. Lewis set out with seven men “in quest of this monster,” and tracked the bear about a mile by following its blood trail. Finally, they found him “still perfectly alive.” Although shot through the lungs by Bratton, the bear had summoned the strength to dig a bed in the soil two feet deep and five feet long. The bear was dispatched with two lead balls to the head. Lewis now had to confess that he did not like these “gentlemen,” and would rather “fight two Indians than one bear.”

Tuesday, May 14, 1805 was a day of near disaster, as a huge grizzly almost made hamburger of the six men who discovered it lying on the ground near the river. They slowly crept up unnoticed within about 120 feet of him and concealed themselves behind a mound of earth. As planned, two of the men held fire while the other four fired nearly at the same time, with all the shots striking the bear. Instantaneously, with mouth open, the bear leaped to its feet and charged the hunters. The two hunters who had held fire shot and scored hits, with one ball breaking the shoulder but still not slowing the charge. The men took flight and ran for their lives. Despite their rapid flight, the enraged bear nearly overtook them before they reached the river. Two of the men leaped into a canoe, and the other four scattered and hid themselves in a patch of willows. Then, reloading their guns as fast as they could, they refired and struck the bear several more times. This volley only served to direct the bear to them and nearly caught two of them. Discarding their guns in panic, they leaped off a 20-foot bank into the river, the bear close on their heels. One of the men standing on the bank drilled the animal through the head, killing him. Inspection of the bear showed he had eight lead balls in him.

On June 14, 1805, waiting for the main party while investigating the Falls area, Lewis had his day of high adventure when he came face to face with a grizzly. Alone and dreamingly contemplating a buffalo he had shot, his rifle not reloaded, he suddenly noticed a bear lumbering toward him, just 20 paces away. To his dismay, while holding an empty rifle, he noticed there was not a tree within 300 yards, nor any depression in which he might conceal himself. He attempted to avoid a charge by walking nonchalantly away, but the bear charged at him “open mouthed and [at] full speed.” Lewis bolted for the river, 80 yards away, and plunged in up to his waist. He then turned and pointed his espontoon (a walking staff with an iron spike) at the bear as it pulled up short at the water’s edge. For some unexplained reason, the bear turned and ran at full pace back across the open plain and disappeared. The bear’s behavior, Lewis wrote, “… still remains with the mysterious and unaccountable… and I felt myself not a little gratified that he had declined the combat.”

On their homeward journey in 1806, the expedition’s documentations of grizzly encounters in Montana shows 11 kills, seven wounded, and 28 sightings. A most dangerous grizzly encounter involving Private McNeal occurred on July 15, 1806, when he was treed by a grizzly at the Great Falls of the Missouri. As reported by a concerned Lewis, “A little before dark, McNeal returned with his musket, broken off at the breech; he informed me that on his arrival at Willow Run, he had approached a white bear within ten feet. The horse took the alarm and, turning short, threw him immediately under the bear; this animal raised himself on his hinder feet for battle, and gave McNeal time to recover from his fall—which he did in an instant—and with his clubbed musket, he struck the bear over his head and cut him with the guard of the gun and broke off the breech. Stunned with the stroke, the bear fell to the ground and began to scratch his head with his feet. This gave McNeal time to climb the willow tree which was near at hand, and thus fortunately made his escape. The bear waited at the foot of the tree until late in the evening before he left him, when McNeal ventured down, caught his horse, and returned to camp.These bears are most tremendous animals; it seems the hand of Providence has been most wonderfully in our favor with respect to them, or some of us would long since have fallen a sacrifice to their ferocity.”

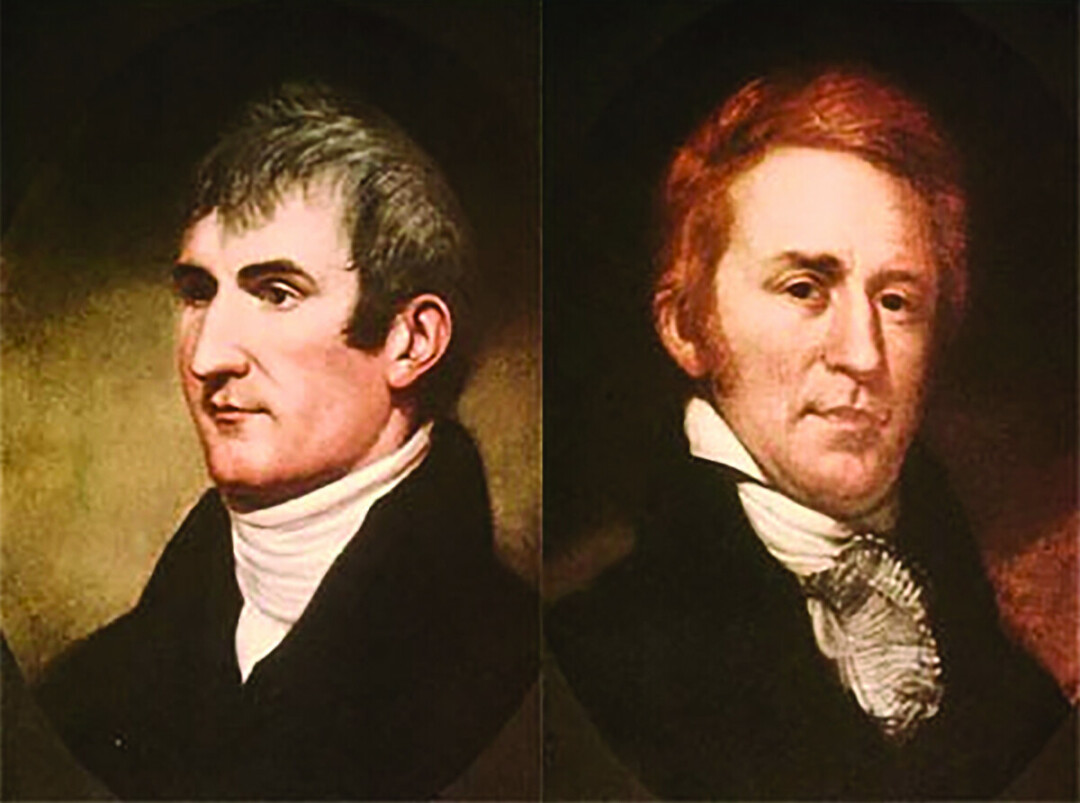

Much of our knowledge of the grizzly and its world at the time of first contact between Europeans and Native Americans comes from the meticulous notes of Meriwether Lewis and his fellow explorers. They passed through a land of “visionary enchantment”prowled by the great variegated bear that one day would become a symbol of so much that was lost. Numerous writers, in later years, would record and link bear myths, encounters, rituals, folklore, and scientific studies throughout North America in ways too numerous to document, and too complex to fully understand here. Suffice it to say that the grizzly has long remained a symbol of American wilderness, a power to fully respect.