The Ground Squirrel Bounty Hunt of 1887

“The following pages contain a list of all parties bringing squirrels to this office with the date, total number of squirrels and names of witnesses.” ~ Charles A. Carson, Probate Judge

Among dozens of nineteenth and early twentieth century county ledger books in the Gallatin History Museum archives is a half-filled journal with the above inscription neatly written on the top of the first page. Though the words may seem unusual today, they serve as a reminder of Gallatin County’s strong ranching heritage.

The word “squirrel” in the ledger book does not refer to the bushy-tailed creature known for living in and climbing trees with ease, but to the ground squirrel — a cousin that spends its life on and under the ground. Burrowing rodents like ground squirrels, prairie dogs, and gophers were (and are) a significant threat to local farming and ranching operations. In addition to eating crops, tunnel holes produced by these critters can be a hazard to horses and cattle. Even before Montana achieved statehood in 1889, the territorial government considered burrowing animals a threat to early farming and ranching operations, and took steps to regulate the population.

On March 5, 1887, the Montana Territorial Legislature approved an amended act which placed a bounty on certain animals at odds with farmers and ranchers. The law updated a piece of legislation from 1883 targeting bears, mountain lions, wolves, coyotes, ground squirrels, and prairie dogs. Hunters were required to bring entire skins to county probate judges or justices of the peace, who in turn would inspect the bounty for signs of fraud in the presence of witnesses. According to a summary of the rule in the Avant Courier on April 7, 1887, bounty animals must be dispatched “within the bounds of the county in which the application for the certificate is made.” Citizens were further warned that no hunting whatsoever could take place on a reservation or in a national park.

If all appeared well, the judge or justice of the peace would issue a certificate for the bounty money, which was paid from the territorial treasury and from the general fund of each county. Perhaps because the law required county officials to dispose of the skins, probate judges and justices of the peace could take a small cut from each bounty paid. One wonders what the county offices looked (and smelled) like during that summer of 1887, when just about every day a fresh load of carcasses arrived.

It must have been difficult for county officials to keep up. As the newspaper reported on April 7, “Since the passage of the new Bounty law, the squirrel crop has been immense. On Monday, one party brought to Probate Judge Carson 453 skins, of which number 93 were caught in one day with eight traps. He received his certificate and went on his way rejoicing. Surely the days of the festive squirrel are numbered.”

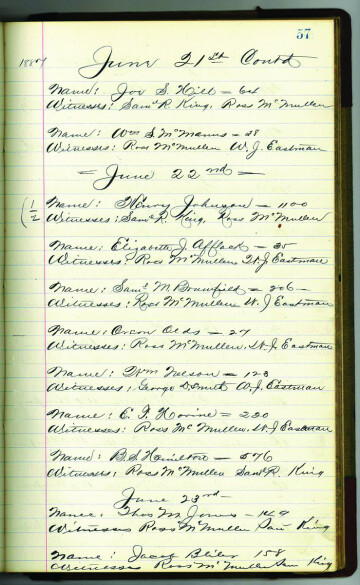

According to the April 7 article, the bounty for each prairie dog was ten cents and the bounty for each ground squirrel was five cents. This translates to about $3.19 for prairie dogs, and $1.60 for ground squirrels in today’s dollars. Locals wasted no time in starting the bounty hunt that spring of 1887, likely eager to earn a little extra spending money. The first entries in the ledger book are recorded on April 7. That day, Frank Lane turned in 101 carcasses, and Martin Lundwall brought in 142. A quick conversion to today’s dollars reveals that Frank Lane made about $162.00 and Martin Lundwall $227.00.

Even local judges participated. On April 14, 1887, the Avant Courier noted that “Judge Didawick has destroyed, during the past week 3,212 ground squirrel skins and Judge Carson about 4,500.” There was likely some debate about this law, as there is with most legislation. It seems probable that the Gallatin Valley, with its heavy farming and ranching focus, was in favor of the measure. The Avant Courier printed this comment on April 21: “Dan Lee, a prominent citizen of Timberline, was in the city yesterday and is all broken up on the gopher and the prohibition rackets. He says an official who can give certificates for 10,000 squirrels during a month can accomplish more than he could if he were appointed public administrator. The festive squirrels will be relegated to the past, but the author of the bill—Mr. Hoffman—will eventually be entitled to the thanks of the community.”

An analysis of the Ground Squirrel Bounty ledger book reveals a couple of interesting things. June was the busiest month, with over 118,000 animals turned into the probate judge’s office. May, July, and August each tallied between 60,000 and 70,000, with April and September being the slowest months. This is understandable, considering that by June, the largest number of ground squirrels would have been running around area pastures, following hibernation and breeding. As the summer wore on and hunting progressed, it makes sense that the number of bounties turned in would have declined.

Because names are recorded in each entry, with a little research we can learn about the people who engaged in this activity. As expected, young as well as old found ground squirrel bounty hunting a good source of income. The name “Reno Sales” appears several times. Reno Sales was born to Charles and Albertina Zahn Sales in Iowa in 1876 and the family moved west in the early 1880s. In the summer of 1887, he would have been about eleven years old. Getting paid to hunt ground squirrels must have been an attractive proposition to many boys—undoubtedly already a familiar activity to many of them.

The Sales family lived near Salesville (now Gallatin Gateway), which was named for Reno’s uncle, Zachariah Sales. Reno Sales attended Montana Agricultural College (now MSU), where he graduated in 1898. He went on to enjoy a long career as a geologist, living and working in Butte. He eventually became the chief geologist for the Anaconda Copper Mining Company until he retired to Bozeman. He passed away at the Bozeman Deaconess Hospital at the age of 92 in May, 1969.

Not surprisingly, most names in the book belong to men. However, a few female names appear, including Elizabeth Afflack. According to the 1880 census, Elizabeth Afflack and her husband William lived at the eastern end of the Gallatin Valley, along with their children Mary (age 12), Elizabeth (age 10), Thomas (age 7), William (age 5), and Ida (age 2). William’s occupation was listed as “farmer,” while Elizabeth was noted as “keeping house.”

The Afflacks were a farming family in the Springhill area. On January 30, 1885, William A. Afflack was granted a land patent in his name for 160 acres near the foot of the Bridger Mountains just north of Ross Creek. This could have been the homeland of the ground squirrels Elizabeth brought to Bozeman twice that summer in 1887. The bounty ledger also contains several entries for William Afflack, and it is likely that William and Elizabeth supplemented their farm income that summer with ground squirrel bounty hunting. In 1891, the Afflack family doubled their land holdings when they homesteaded another 160 acres on Middle Cottonwood Creek, near today’s junction of Walker and Toohey Roads.

Young girls also tried their hand at squirrel hunting. Two other female names that appear in the book are Eliza (or Elisa) Godson and Sarah M. Lowe. Eliza Godson was born in 1880, so she was a bounty hunter at seven years old. One of the last entries in the ledger records Eliza’s 38 ground squirrels, brought in on September 17. Sadly, Eliza died in Bozeman in February 1901 at only twenty-one years of age. Sarah Marie Lowe was born in 1874 to George and Nancy Lowe. The Lowe family came to Montana in a covered wagon and ranched near Salesville for a few years until they moved into Bozeman. Sarah married Edmund Burke, professor of chemistry at Montana State College. Sarah died of a stroke in 1934 at the age of sixty.

Josias and Lucinda Pinkerton

The ledger also confirms that hunting was a family affair. Josias and Grant Pinkerton appear multiple times in the book. Josias and his wife Lucinda moved west from Iowa in the 1870s and ranched near Salesville. Their son Grant (Ulysses Grant Pinkerton) was born in 1869, and ran a dairy farm near Salesville. Grant or Josias Pinkerton are listed nine times in the bounty ledger, and very well could have been the top-performing hunters that summer. Between the two of them, they brought in nearly 17,000 animals.

A count of ground squirrels recorded in the Ground Squirrel Bounty ledger book reveals a staggering grand total of over 354,000 animals hunted from April 7 through September 19, 1887. The bounty on each animal was five cents, which means Gallatin County paid out nearly $18,000 that summer in ground squirrel bounties alone, which translates to over $500,000 in today’s dollars.