An Ultimate Road Trip

“... And then the lights of Bozeman – the broad main street ablaze with power of brightness and abundant light...”

The above quote comes from an odd little book; almost without sentences, it’s just daubs of phrases strung together, notes intended for a later prose construction that never occurred. The book is A Western Journal, by Thomas Wolfe. He is describing driving into Bozeman on a summer evening in 1938. Wolfe and his two companions were nearing the end of an extraordinary road trip through the western U.S. National Parks.

Thomas Wolfe, a native of North Carolina, rose to prominence as one of America’s most acclaimed novelists during the 1930s. He grew up in a large family in Asheville, and attended the University of North Carolina, editing the campus newspaper and studying theatre. After graduating in 1920, he moved to Harvard to concentrate on playwriting. His plays were performed within the university but when, after receiving his master’s degree from Harvard, he attempted to sell his plays to Broadway he found no success—because of their great length. This almost furious proliferation of words was characteristic of all the writing he did throughout his life.

Deciding that his style was more suited to fiction than the stage, he concentrated on prose while working as an English instructor in New York City. Wolfe found commercial and critical success with the publication of Look Homeward Angel in 1929. This was followed in 1935 by a second novel, Of Time and the River. Submitted to Scribner’s publishing house, these novels were edited by Maxwell Perkins, who was also the editor for Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

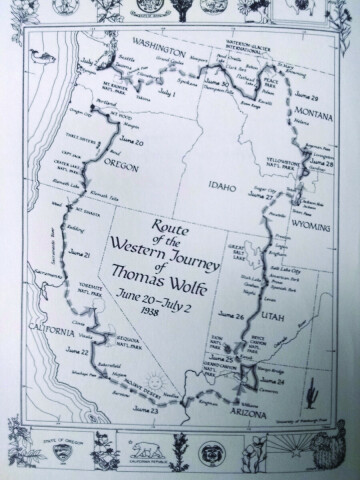

Wolfe spent most of his time in New York and Europe. After submitting a manuscript of over a million words to his publisher in 1938, an exhausted Wolfe determined to travel, in order to experience more of the United States. After stops to give lectures at Purdue and in Denver, he took the train to Seattle. At a party, he learned of a trip being organized by Raymond Conway of the Oregon State Motorist Association, and Edward Miller of the Oregonian newspaper, as publicity for the western national parks. They proposed to visit all eleven parks in the span of two weeks, the length of an average person’s vacation. Wolfe was invited to come along (or invited himself). The two other men agreed and picked up Wolfe who, as he had never learned to drive, folded his six- foot, six-inch frame into the back seat of the small coupe they were driving for the whole journey. They left Portland on June 20th, 1938.

The trip encompassed 4,500 miles, eight states, and 11 Parks: Crater Lake, Lassen, Yosemite, Sequoia, Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce, Grand Teton, Yellowstone, Glacier, and Mt Rainier. The route began in Portland, passing Mt Hood, then down to US 97 to Crater Lake; then to Klamath Falls and US 97 to Weed, and then US 99 past Mt Shasta. On to Sacramento, through the Sacramento River Valley. Lassen was designated a National Park in 1916; the road to it was completed in 1931. The travelers then switched to US 99 down to Merced, then over to Yosemite… south to Clovis and into Sequoia. They then headed back to US 99 south to Bakersfield, then went east to Mojave, picking up the famous Rt 66 at Barstow, which brought them to Needles, Kingman, and Williams. From there, they went north to the Grand Canyon, over to Cameron and US 89, crossing the Navajo Bridge, on to the North Rim.

They hit Kanab, then Zion and Bryce and US 89 again, drove all through Utah, then took local roads up to Pocatello and Sugar City, to Driggs and over Teton Pass to Jackson and Grand Teton Park. Through Yellowstone and back to US 89 at Gardiner to Livingston. West to Bozeman over the pass into the Gallatin Valley. North to Helena and back to US 89 to Browning, into Glacier Park, south past Flathead Lake to MT 200 at Ravalli. Across the Idaho Panhandle on US 2 and south to Spokane. North to Grand Coulee, south to Ellensburg, west to Mt Rainier Park. Finally, to Tacoma and Olympia, where the trip ended on July 2nd, lasting less than two weeks from beginning to end.

The three men realized that their trip was a stunt. Wolfe commented; “The gigantic unconscious humor of the situation... ‘making every national park’ without seeing any of them – the main thing is to ‘make them’ – and so on and on tomorrow.” Yet, they appeared to have a great time, Wolfe jotting superlatives about the scenery and keen observations about the people they encountered. There were no interstate highways in 1938. Sixty mph was the top speed on the U.S. two-lane highways. Four thousand five hundred miles was a very long way. Approaching the last Parks of the trip, their pace slowed. After a night in Pocatello, they spent a day driving through Grand Teton and into Yellowstone, spending that night at the Old Faithful Inn. Another day in Yellowstone ended with dinner in Livingston and the night in Bozeman. The next day was spent driving through Montana, with an overnight in Glacier Park.

They paused at the top of Bozeman Pass to read a Lewis and Clark historic sign, then were dazzled by the lights of Bozeman. Wolfe’s notes tell of a hotel and of bar hopping. His account is not more specific. The Baxter was the premier hotel at the time. The rooms were advertised as fireproof, and rates began at $1.75 per night. The hotel was designed by prominent Bozeman architect Fred Willson and opened in 1929. In the 1930s, it featured two restaurants and a lounge. Wolfe probably began his bar hopping there, along with Miller. He could have watched Loretta Young and Joel McCrae in Three Blind Mice featured at the Ellen Theater that night (June 28th, 1938). He does not mention going to a movie. After putting Miller to bed, Wolfe ventured back to a bar or two, and finished the evening with a hamburger and a glass of milk.

At breakfast the next morning, he could have purchased the Chronicle for a nickel. The headline reported the Spanish Civil War raging in a hot, barren sector northeast of Madrid. Bob Feller had pitched the Indians 7-3 over the Red Sox to go five games up on the Yankees. Over in the National League, the Reds were two games up on the NY Giants. Jimmy Foxx of the Red Sox was leading the majors with 21 home runs.

After breakfast, the men could have gone to Chambers Fisher and purchased shirts 2/$1.10. The long, quick trip surely left no time for laundry. Kentucky whiskey was selling for $1.65/qt. They probably gassed up at Swanson’s Standard Station at Main and Grand. Soon they left town for Helena, thus missing the film of the Joe Louis/Max Schmeling fight being shown along with the feature that night at the Ellen. They also missed the thirteenth annual Livingston Roundup just a few days later, July 2-4. But the road beckoned once again.

Wolfe noticed the Bridger Mountains to his right and the Rockies to his left (the Gallatin range, I’d imagine). On to Helena and the “Gates of the Rockies” and the “bankfull Missouri.” Then the “Great American Plain opening with infinite lift and rise and vastness to the fore – so towards the Rockies and the lift and rise and heaving of the Earth Mass... .”

He was moved by Montana, by the trip, by the west. In a previous story, Wolfe had stated; “I will go up and down the country and back and forth across the country... I will go out west, where the states are square. I will go to Montana and the two Dakotas and the unknown places.” Wolfe had feared that he would die young, and that may have been what inspired him to write so much. In the last twelve years of his life, he produced millions of words. His western trip was intended as a break after delivering a massive manuscript to his publisher. A few days after the trip, he wrote to his editor that he had a book of notes to revise and round out. While beginning this project in Seattle, he became ill with pneumonia. His condition worsened and he was transported east to Johns Hopkins. During surgery, a rare form of tuberculosis was discovered in his brain. Thomas Wolfe died at the age of 38, less than two months after his Western Journey.

From an introduction by Maxwell Perkins of an edition of Look Homeward Angel, Thomas Wolfe’s last novel, published posthumously:

“... He was in his very nature a Far Wanderer, bent upon seeing all places, and his rooms were just necessities into which he never settled. Even when he was there, his mind was not. He needed a continent to range over, actually, and in his imagination. And his place was all America.”