Binding Them in a United Organization | Strikes in Bozeman History

Recent national labor and union strikes have stimulated some interest in what those actions mean for an industry or a community. Striking usually involves a group (often employees, but not always) halting normal operations in an attempt to gain a desired outcome from leadership. Two interesting strikes in Bozeman history involved social, rather than employment issues. Both sparked change in the Bozeman community.

The first strike involved students at Montana State College. It began on the evening of Tuesday, November 11, 1930. According to the Montana State College Weekly Exponent newspaper, at a Pan-Hellenic meeting, Dean Una B. Herrick notified students of new changes to the school’s social policies. The Exponent summarized: “The important change from the old regulations was that M.S.C. co-eds were to be in their respective dwellings by 11 o’clock on week-end nights (Friday and Saturday) except when they were attending a registered college function.”

Fraternities and sororities were the first to hear the new ruling, and tempers flared. By the next morning, an “Appeal for Freedom” flyer had been printed and distributed campus-wide. Students debated the issue and decided the new ruling was “an infringement of their rights.” The student body met in the school gymnasium (now known as Romney Gym), chose leaders, and agreed upon an additional six new privileges to request of the faculty. Meetings between the student leaders and the faculty social committee accomplished little, and by the evening of November 13, the majority of the student body agreed to boycott classes until a satisfactory agreement was reached.

The student strike began with a picket line on Friday morning, November 14, 1930. According to the Exponent, only “a mere handful of students attended classes.” In a history of Montana State University, published in 1968, historian Merrill Burlingame noted “...students who indicated that attendance at classes was a matter of conscience with them were admitted. Not more than a dozen or so were afflicted with a conscience in the matter.”

Montana State College President Alfred Atkinson was out of town during the strike. In Washington, D.C. to attend a Land-Grant College Association meeting, Atkinson was likely bombarded by telegrams. On Monday afternoon, Atkinson messaged the students that while he was always happy to “confer and cooperate” regarding school regulations, he would not act under threat and advocated a meeting following his return to Bozeman. The Exponent quoted Atkinson: “College supported by public at substantial expense each day and students must resume classes in the morning.”

According to the version of events published in the Bozeman Courier on November 21, the faculty social committee did ultimately agree to extend the curfew for female students on Friday and Saturday nights. They did not, however, agree to give permission for student rallies, or for members of “the Student Senate [to] have equal representation on the faculty social committee.” Despite this, the students ultimately decided to end the strike and return to class. They held another meeting at the Ellen Theatre in downtown Bozeman on Tuesday, November 18. Students decided to resume school the next day, “with an understanding that a conference with the president will be held when he returns to Bozeman.”

The Bozeman Courier complimented the students and commended them for their peaceful demonstrations. “During the strike, there developed a strong college spirit among the students, binding them in a more united organization which revealed their loyalty to the college.” However, upon President Atkinson’s return to Bozeman, he met with students and faculty, and expressed his disappointment with what had occurred. A follow-up article printed in the Courier on November 28 revealed Atkinson’s dismay at the lack of thought for the long-term effect on students, potential future employers, and even taxpayers. “Disregard for authority, the president stated, works to the discredit of the students.” The MSC strike of 1930 could be deemed a success for the students. In the end they managed to lengthen their curfew to 1:00 am on Friday and Saturday nights. They also gained a voice in university policy-making that pertained to student social issues.

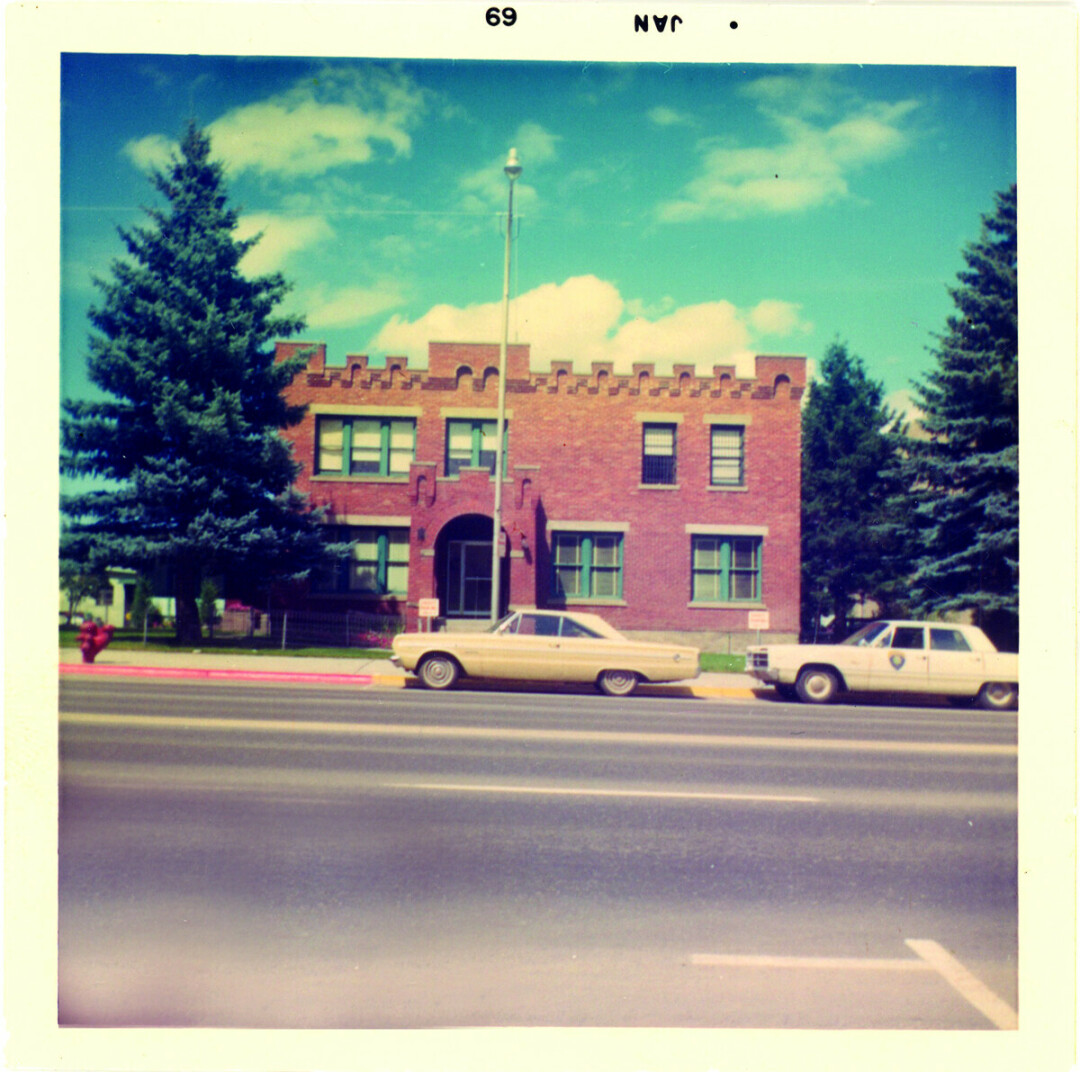

Another group of local strikers began their crusade on the morning of January 7, 1974. Like the college student strike forty years earlier, this new strike was also unrelated to employment or labor issues. On that January morning, eight inmates in the Gallatin County Jail skipped breakfast and began a week-long hunger strike. According to a Bozeman Chronicle article published on January 7, the inmates requested an improvement in living conditions at the jail. In a letter written by the inmates and shared with the Chronicle, one of their major concerns was the amount and quality of food provided them. “(We) are requesting more food with greater variety and better nutritional balance... commissary facilities are lacking and inefficient for getting tobacco and candy or other foods to supplement the diet and break the monotony. The only recreations are the one small transistor radio, playing cards, and some dog-eared paperbacks. There is no television, and the newspaper from the subscription held by a prisoner arrives late, if at all, and has been censored to the point of removing all of the comics on a Sunday.” Other complaints included a lack of adequate heat in the building, and strict visitor restrictions.

Sheriff L.D.W. Anderson addressed the issues put forth by the prisoners in the same Chronicle article. Anderson explained that the prisoners received two meals each day, prepared by his wife Thelma and a relief cook. He listed items typically on the menu, which included eggs, cereal, baked beans, hot dogs, bread, pears, canned vegetables, cake, ice cream, and donuts. Sheriff Anderson shared that in the previous six months, the average daily grocery bill for the inmates was $36.10 (equivalent to approximately $225.00 today). Anderson calculated the average cost per inmate per day at $2.32 ($14.45 in 2023). The prisoners, on the other hand, estimated the cost per day at “between 50 cents and $1.25.” The prisoners’ estimate converts to a range of just over $3.00 to nearly $8.00 in today’s dollars.

In the article, Anderson also addressed a few of the inmates’ other concerns. He stated that, indeed, a television used to be provided but was no longer, “because the prisoners kept tearing it apart.” In reference to the reduced number of visitors allowed the inmates, Anderson commented; “This is not a hotel we are running.” He did concede that the sixty-year-old building had some issues, among them adequate heating.

Over the next several days, the Chronicle printed a daily article on the hunger strike, noting additional clarifications to the prisoners’ demands, and updates on the inmates’ health. Striking inmates admitted that the coffee provided was actually “very good.” In turn, officials were able to fix the heating issue, ending, at least temporarily, the cold cell block. Quantity and quality of food continued to be the major point of contention, and the Chronicle reported that the inmates requested a visit from a federal jail inspector. In a January 11 article, the newspaper quoted the inmates’ spokesman: “If an inspector does come, we are sure that he will insist the county make the same kind of changes we have been requesting all along.”

The Chronicle reported that during the hunger strike, food was still served to the inmates. Eight men participated in the strike, but several more were incarcerated in the jail at the time. The non-striking prisoners enjoyed the extra food not eaten by their striking comrades, which, according to the Chronicle reports, caused no ill-will between the prisoners. The eight striking inmates subsisted on coffee, water and lifesavers until they ended their week-long fast on Sunday afternoon, January 13.

On January 14, a short article reported on the end of the strike. The Chronicle remarked that it appeared little had changed as a result of the prisoners’ actions. Sheriff Anderson claimed his office had not negotiated with the inmates, and that no federal jail inspector had come in answer to the prisoners’ demands. Anderson assured the public that the inmates were healthy, and the article concluded with the comment that, “The ones who appear to have gained most from the strike were the other five prisoners in the jail.”

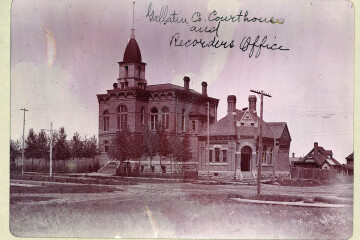

While newspaper reports suggested that public feedback on the events was mostly against the prisoners, press coverage of the hunger strike did bring certain issues to the forefront. County officials admitted in news articles that they believed the old county jail was outdated. Officials acknowledged that, besides the heating problem, prisoner safety and security was an issue, and exercise areas were nonexistent. Though the hunger strike appeared to have been mostly unsuccessful at realizing short-term gains, inmates’ actions did have long-term consequences for the better. Historian Merrill Burlingame noted in the publication Law and Order in Gallatin County that a lawsuit based on “unsafe food services and unsanitary conditions” at the aging county jail was introduced in March, 1981. In 1982, only eight years after the inmates’ hunger strike, a new state-of-the art Gallatin County Detention Center replaced the overcrowded, outdated 1911 Gallatin County Jail.

Both the 1930 Montana State College student strike and the 1974 Gallatin County Jail inmate hunger strike represent local examples of people intent on forging change. Both strikes were successful in different ways, and contributed to the dynamic Bozeman community.