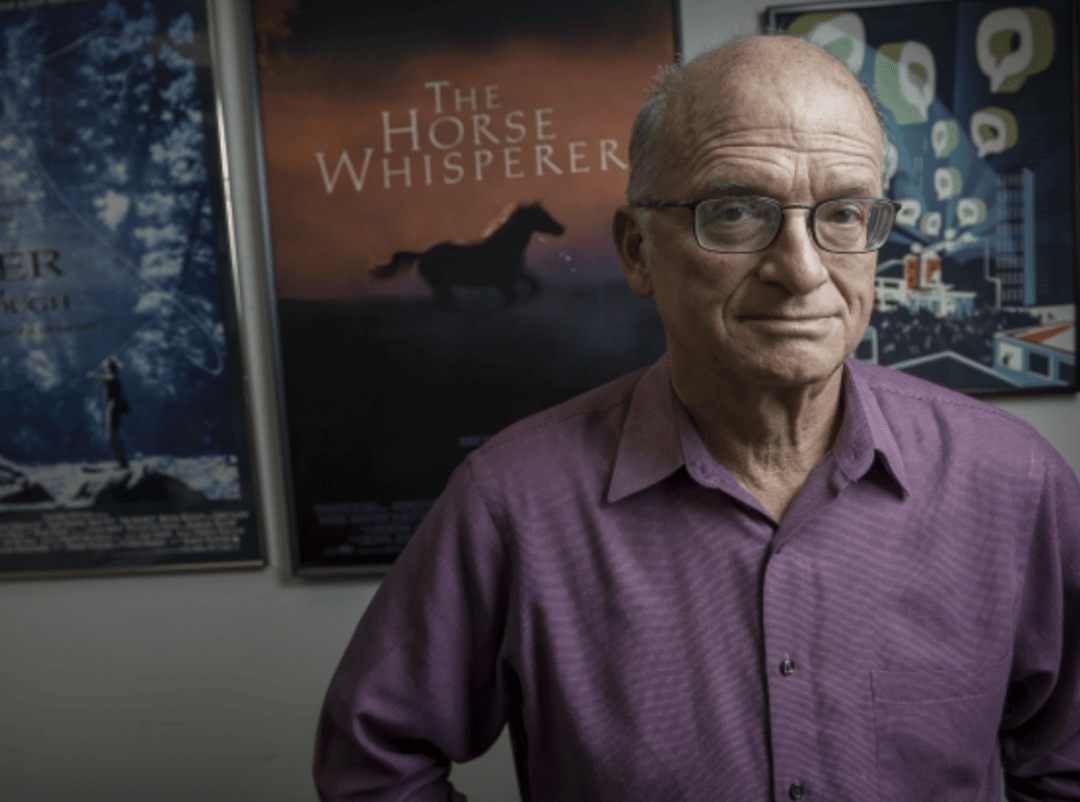

MSU Film Professor Dennis Aig’s Mantra: Embrace the Chaos

Dennis Aig recently retired after 34 years at Montana State University. As a professor in the College of Arts and Architecture’s School of Film and Photography, and while traveling the world working on films, he influenced generations of students in the classroom and on film sets.

Born in Brooklyn, Aig grew up in Queens. After receiving a bachelor’s degree in New York, he moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he met his wife and obtained his doctorate at Ohio State University. He majored in English but became interested in motion pictures, inspired by classic movies of the 70s, like “Jaws,” “The Godfather,” “Mean Streets” and “Star Wars.” The five-time, regional Emmy winner started making films for an Ohio corporation and eventually moved to Montana, the home state of his wife, Ann Bertagnolli, where he took a job at MSU, teaching and making films for Montana PBS.

The following interview is reprinted with permission from MSU; it has been edited for brevity.

Greg Cappis: Was “Shadow Casting: The Making of ‘A River Runs Through It,’” the first big, successful film that put your career on the map?

Dennis Aig: Yes, “Shadow Casting” had two things going for it. It was a film about a film that became a hit film. We thought the title was terrible – “A River Runs Through it” – runs through what? It was for Montana Public Television, and had students working on it.

The students were outstanding. It was the perfect blending of the academic and the professional. We had real movie stars and filmmakers in our film, so we had to be at the top of our game. The students graduated during the movie; we had to ask for a day off so we could all go to graduation.

It’s still one of the best films I’ve ever worked on… It was about “A River Runs Through It,” but also about how a film was made. Back then, there weren’t a lot of ‘making-ofs.’ It established the station, me, the guys. The funny part was, we got nominated for regional Emmys and didn’t win anything. We were all there in our tuxes, sitting at this table with people winning, like,12 Emmys. It was OK… we won other awards.

GC: All your films have involved students in the production. How did that come about, and why is it important?

DA: I always tell my production management class: I can teach you process, but I can’t teach you what it’s really like. I can tell you what to do, but I can’t tell you how to do it, because every film is different. Immersing students in an actual movie with experienced filmmakers is the best way to learn.

Film school is very important—you learn analytical skills, history, and basic technical skills, but the field changes almost daily. Until you are with professionals, you can’t really see how it happens, how they work together.

On my science and natural history movies, the students were more the lead than I was. Like an executive producer, I guided them but, because the students in that case had scientific backgrounds, some were better suited at doing those films than I was.

GC: How did you help build the MFA program in science and natural history?

DA: I tried to promote good relationships with scientists on campus. We are a very busy science research school, but people don’t realize how hard the scientists work. In the summer they’re writing grants. They’re in the field, not in hotels. I was out on boats in the Gulf of Mexico sleeping in these coffin-like beds. I was sharing tents with people out in New Zealand and Australia. A lot of hard work goes into scientific research.

GC: Is that where you draw similarities between producing and teaching?

DA: Yeah. Producing is a lot like teaching, especially when you have newer people. There are certain principles to follow, but there are differences in degree and finances between a feature and something like science and natural history.

The biggest compliments are when my former students ask me to help them produce their films. Phil Baribeau did that. We did “Unbranded” and “Charged” together. Christine Cooper did that with “Youth v Gov.”

It’s modeled on George Lucas; he did the first “Star Wars,” then didn’t want to direct anymore. He asked his directing teacher from USC, Irvin Kershner, to direct “The Empire Strikes Back,” which most people consider the best of the first three films.

GC: What do you enjoy about producing?

DA: Its many aspects. What I always say is, the Best Picture Oscar goes to the producer, technically. They have everybody come up on stage, but the one who accepts the award is the producer. The fact that this film got made, got finished, and was as good as it was, is largely the part of the producer(s).

GC: What do you enjoy about teaching?

DA: The sense of continuity. I learned something new on every project, because the field constantly changes. You’re able to give your students a little head start, because textbooks are out of date by the time they’re published. That’s one of the reasons I always wanted to keep active professionally, even though having a dual career can get exhausting. I wanted to be able to tell my students, ‘here’s how things are happening now,’ or ‘here’s what people are doing now.’

“Embrace the chaos,” you said, was a throwaway line in a lecture.

GC: How did it become a mantra?

DA: Film looks like chaos. You have people doing different things in different places. Even on small documentaries, you don’t know what’s going to happen. When you get there, you think it’s going to be a beautiful day and it’s raining… or, you’re out in the middle of God knows where. Or you have a ‘difficult’ interview subject who turns out to be great. You have to love that — the idea that if you make a mistake, the deep end is not too far away, but if you do it right, higher ground is there, too.

GC: Over the course of four decades or so, how have you seen the industry change?

DA: When I got hired, I did my first digitally edited show. Before then, we cut film; now we have digital cameras. Students are interested in shooting film because they haven’t done it. Before, we always started them on film. Now, you can emulate film digitally almost as well as you can shoot it, and it costs less. You’re getting virtual studios, like “Mandalorian.” It’s all shot in the studio—like going back to the way it was in the 1930s. They didn’t go on location unless they absolutely had to. In the 1950s movie “The Searchers,” they actually went to Canada for a three-minute sequence. In “Mandalorian,” the exteriors look like they’re outside. They’re not. There’s a lot of following incentives to different parts of the country and the world, especially Canada, to shoot.

Markets have changed. Now, the international market is very important, so you find films being developed based on where the market’s going to be.

Film is an art, a craft and a business. You have to keep those in balance: You can have an exquisitely shot, wonderful film, but if you don’t make it so someone wants to go see it, they won’t. It takes a lot of different skills.

GC: Is there one type of filmmaking you prefer?

DA: Not really. I get as excited about a good documentary as I do a good dramatic film. Some of the skills are the same [though] there’s a difference in scale. Dramas take acting, makeup, costuming, and everything else you don’t have in documentaries. It really depends on what the subject matter is.

GC: Phil Baribeau said you were offered another position at the university as program director right after accepting the role for “Unbranded.”

DA: I was director of the film school for three years. This is talking about embracing the chaos, writ large, exponentially. I was the only one who had rank. I said; ‘All right, I’ll do this for three years, but I have to check with the “Unbranded” guys.’ I think Phil said something like, ‘Yeah, if you’re crazy enough to do that, go ahead.’ So I didn’t sleep for like three years. But I don’t regret it. “Unbranded” was a once-in-a-career type of experience.

GC: Everyone I talked to wanted me to ask, Do you sleep?

DA: Yes, I do, on occasion. You can only do this for so long. “Unbranded” was a perfect example. I remember sending an email out at 2:30 a.m. That’s one reason I’m retiring, so I can get more sleep.

GC: How were you able to balance everything? I heard you have a great family, too.

DA: It’s very hard. My wife, Ann Bertagnolli, is a rock star in her own right. She heads MSU’s INBRE program. Occasionally, my kids worked on the films. When they were very young, they acted in “Guide Season.” One of them helped with the horses in “Unbranded.”

GC: How many kids?

DA: Two, and a granddaughter. I’ve been at the university for over 30 years. I think all professors have the same kinds of issues. Making movies, doing fieldwork or lab work… all require a certain obsessiveness that can affect other parts of your life. I’m very fortunate that people in my family understood it.

GC: How old are you now?

DA: Seventy-three.

GC: Still working on films?

DA: Yeah.

GC: What’s your plan going forward?

DA: I have the thriller movie, “Thine Ears Shall Bleed,” about Barbara Van Cleve, to finish with Lynn and Jim Kouf and Ben Bigelow; we’re looking for distribution. We had students work on that, too.

GC: Any other career highlights?

DA: We did a lot of things to make the MFA program more accepted on campus. It was initially an experimental program. Film work in areas that have become very important, like climate, like the “Youth v Gov” lawsuits. One of the highlights is seeing your students do so well and accomplish great things. Obviously, I didn’t do it by myself, like the work of all professors, but it gives you the satisfaction of, ‘well, we must have been doing something right.’

Phil (Baribeau) with “Unbranded.” It took a lot of creativity to figure out how to do that—you could only have two shooters at any one time. Phil came up with a horse having all the sound gear on it. Luke, the sound horse, actually gets credit in the movie. They were one of the first groups of people to take horses through the Grand Canyon.

There have been a lot of highlights. “Deep Gulf Wrecks” — we found a U-boat. I did a thing with shamans. It became “Bridgewalkers.” Just to see how shamans actually work in native environments.

GC: What are some of your favorite films?

DA: The ’70s films were very influential. The “Godfather” films, “Chinatown,” “Mean Streets,” all that stuff.

Spielberg stuff, and some of the classics, because that’s what I studied in my dissertation. “The Big Sleep” is still a great film that nobody can really answer questions about. “To Have and To Have Not” shows the strength of dialogue… musicals. Even guilty pleasures, like really bad films. “Spinal Tap,” because I did some music videos, too. “Spinal Tap” just hit it; there are all sorts of Beatles references, and feuding girlfriends. So, the ’80s was a very good time, too.

I have a lot of favorite films. “Citizen Kane,” from my generation. I first saw it when I was 14. I had never seen a film shot like that, sound like that; some of my students find it slow moving, but it influenced generations. One of the issues in “Godfather” 1 was its classic structure; the whole movie is actually in the wedding scene. All the characters are at the wedding, then it branches out into the individual stories. I used to diagram the plotlines for my classes when I taught script writing. When you’re in production everybody says, ‘we can’t have all these plotlines’, or ‘we have to simplify it.’ I said, ‘there are six or seven plotlines going on in “The Godfather,” and I’ve never met anybody that can’t follow the story.’

GC: Anything you would like to add?

DA: I really appreciated the faculty I worked with, my colleagues, and the staff. We’ve been very lucky to have great staff. Also, to see Montana PBS blossom into one of the strongest smaller stations in the country is great.