Chet Huntley: Anchoring Big Sky Part 2

Read Chet Huntley: Anchoring Big Sky Part 1 here

In the summer of 1970, a recently retired national news broadcaster, instantly recognizable anywhere in the country, moved to Bozeman. A native Montanan, he and his wife rented a house, and he began a long-dreamed-of project—to build a new ski resort in this area. His name was Chet Huntley.

Though he had not resided in Montana in nearly forty years, Huntley had never forgotten his boyhood and young adult time here. It was part of his persona, and carried him around the west as a radio broadcaster and, eventually, to television success in the east. He had family connections in Billings, where his mother and one of his sisters lived, and owned a cattle ranch in the state. But in 1970, he resumed life as a full-time Montanan, and as a promoter and builder for the project he had conceptualized years earlier.

By the mid-1960s Huntley had been talking about his eventual retirement, and coming home to Montana. He began to consider the purchase of a ranch with other investors, as a vacation spot and a tax-write off. Chet and his wife Tippy often vacationed at the 320 Ranch in Gallatin Canyon. He let the owner know that he was interested in property somewhere in the area. He was told of a ranch available on the Gallatin West Fork.

In The Generous Years, an autobiography about his childhood in Montana, Huntley wrote about the family’s impending move from the plains near Saco, Montana, to the Gallatin Valley: “Mountains had become something of a modest obsession... a Montana mountain. Its alluvial fans sweep down toward the valley, which it invariably dominates. A mountain or mountain range is forever so magnificently and perfectly based, all in proportion, its shoulders and snow crown in dimensional harmony with the massive and gently ascending foothills on which it is set.” This passage seems almost to have been written with Lone Mountain in mind. Image looking down from the Lone Mountain Tram 2024: Nick Oldham

Image looking down from the Lone Mountain Tram 2024: Nick Oldham

The idea of a personal vacation ranch grew into something more—a new ski resort. The land that became Big Sky on the Gallatin West Fork consisted primarily of two ranches that had grown and changed ownership quite a few times in the 20th century; the Crail Ranch and Lone Mountain Ranch. Huntley solicited corporations for funding, primarily, Chrysler. He was made chairman of the board, with a one percent share of the stock. In several transactions, Big Sky of Montana, consisting of nearly 11,000 acres, took shape.

Chet Huntley was the perfect person to undertake such a project. He was a nationally respected and recognized television newsman, and a native Montanan with strong ties to his rural origins. He called the Governor and requested the use of the name “Big Sky.” The phrase was being used as a tourism promotion. A B Guthrie, who had coined the name as the title of his novel, had no objection. The Olympic champion Jean Claude Killy was brought in to evaluate the suitability of Lone Mountain for skiing. Arnold Palmer was hired to design the golf course in the Meadow.

Chet and Tippy joined the Bozeman community, making friends with farmers, ranchers, business owners, and MSU faculty members. Chet talked a lot about retirement but never fully embraced it. He spent about a month each year in New York tending his various business interests, and taped a five minute national news commentary five days a week. The final one was broadcast the day he died.

Chet Huntley was enthusiastically accepted in the Gallatin Valley. His vision of Big Sky was also widely applauded. Supporters included the Bozeman Chamber of Commerce, MSU’s publication The Exponent, The Billings Gazette, KBMN Radio, and the Bozeman Chronicle, which praised Huntley as possibly “the catalyst that changes the way of life in Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley.” Even the Montana Department of Fish and Game was on board. Montana Senator Mike Mansfield stated that Huntley had considered all the angles of his project.

Big Sky was seen as an economic driver that could benefit the area without the degradation that had plagued Montana for generations; logging, ranching, and especially mining had led the economy, but all had their negative aspects. Skiing and other recreation was seen as clean for the environment. However, there were opponents and challenges.

Objections to Big Sky centered around concerns for the environment, wildlife, and a general mistrust of corporate involvement. It seemed that almost everyone liked Chet Huntley but some questioned him representing a group of outside corporations gaining control of an important part of Montana. At least one formal group was organized to lobby the Forest Service against a couple of land swaps that were essential to the project. These challenges set the development back for some time. Those obstacles were overcome, but the same group sued to stop federal highway funds from being used. This suit was successful; the fact that the road up the mountain remained unpaved for years was partly due to this outcome.

Chet Huntley attended and chaired countless meetings that both supported and defended his project. He was a powerful and fervent advocate, but some of those who applauded his return to Montana were leery of verbal promises. At times, Huntley lost his temper with this opposition. He loved Montana and saw his project as bringing economic growth in a clean way. His family was a victim of the boom and bust cycle that had plagued the area since its settlement over a hundred years previously. Despite years of backbreaking toil, they had lost their homestead to the vagaries of the climate. They were lucky enough to remain here because of his father’s railroad job, but they never quite achieved prosperity. Chet worked during his entire school career to help out. He envisioned Big Sky to be a way for his personal success gained elsewhere to be a positive contribution to Montana. Lone Peak Tram 2024: Nick Oldham

Lone Peak Tram 2024: Nick Oldham

One of the original opponents of Big Sky said that our area should concentrate on MSU and agriculture. These aspects have been successful, but much more has occurred in the fifty years since Big Sky was dedicated. Some would bemoan that growth, others would express delight.

Progress is surely preferable to decay. The conundrum is that complete control of the speed, course, and type of progress is not possible. Big Sky is a big portion of our history.

It is not known whether Chet Huntley was aware of any health issues when he was planning his retirement and return to Montana. He had talked about it for a long time, and saw it as moving on to a new challenge and phase of life. A lifelong smoker, there are few pictures in which he is not holding a pipe or a cigarette. In December of 1973, in the midst of working on the opening of Big Sky, he was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died the following March, just a few days before the dedication of the resort.

His retirement to Montana had lasted less than four years but he appears to have thoroughly enjoyed himself and was able to see his dream project through to completion. A story is told about a tourist coming to the Big Sky office in the early 1970s and asking the whereabouts of the famous newsman, Chet Huntley. He stated that surely Huntley did not come into this little office in the woods every day. When the secretary confirmed that Chet was not in, the tourist smirked—until she added that he was out back mowing the lawn.

After Chet’s death, the new resort experienced problems. External issues included the energy crisis and a national depression. Internal challenges included the management of substantial debt. Tippy Huntley continued to live at Big Sky and to serve as a spokesperson for the resort. In 1976, the board of directors voted to sell the resort to Boyne USA. In the last few decades, Big Sky (along with the Yellowstone Club and Moonlight Basin) has seen phenomenal growth.

Of course, it is unknown what Chet Huntley would have thought of the developments of the last fifty years. Surely, as a graduate of a one-room schoolhouse in Saco and a small high school in Whitehall, Chet would be proud of the Big Sky community with its new school buildings and competing sports teams. The problems of the 1980s and 1990s, which were overcome with persistence and further investment, could have been fatal without the continued growth that occurred. Bigger and better has meant surviving and thriving. As Chet Huntley himself said; “Journalists do not write conclusions. Historians do.”

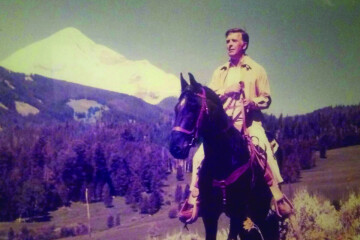

Today, visitors, and even residents of Big Sky, may not know the story of its founding, or of its founder. He is still remembered at the Huntley Lodge, and in the cozy atmosphere of Chet’s Bar. An image persists of a man on horseback riding through a summer meadow below a huge peak streaked with melting snowfields.

Read Chet Huntley: Anchoring Big Sky Part 1 here