Gallatin Licks Polio Danger: The Local Crusade to Eradicate Polio

Ernest Monforton, Mary Kay Lindvig, Harold Lindvig, and Joe Garry (left to right) stand with a Hereford heifer in the sale ring at the Montana Winter Fair. Monforton donated the heifer to a polio campaign, and the animal brought over $700.

April 2024 marks the seventieth anniversary of a significant event in America’s fight against the deadly poliovirus. Polio was a serious concern for Montanans in the first half of the twentieth century. Though not the first polio epidemic in Gallatin County, an outbreak was reported in the 1943 Bozeman Courier. Dr. A.D. Brewer of the city-county health department attempted to calm fears. He explained in the newspaper article that most cases were mild and polio did not seem to be extremely infectious. Just ten years later, Gallatin County had the distinction of being a test area for the brand-new polio vaccine, developed by Dr. Jonas Salk of the University of Pittsburgh.

In some individuals, poliovirus caused flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, digestive issues and fatigue. Occasionally, the virus attacked the central nervous system and caused extreme muscle weakness and paralysis. If paralysis was severe enough and affected muscles used in breathing, the disease could be fatal. Poliovirus was especially prevalent in young children and in the early twentieth century was often referred to as infantile paralysis. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, or March of Dimes, was instrumental in early polio relief efforts nationwide. Before a vaccine was available, one tool that medical professionals used to fight the disease was gamma globulin—a serum including poliovirus antibodies. Though not a vaccine, gamma globulin treatments offered some defense against polio. In the summer of 1953, children in Park and Custer counties were given gamma globulin immunizations after fears of a major polio epidemic.

Polio patients who experienced muscle weakness and some paralysis relied on leg braces to stand or walk. Sometimes, seriously paralyzed patients needed use of an iron lung to survive. Iron lungs were large chambers that surrounded a patient and, through changes in pressure, allowed paralyzed patients to breathe. In the December 9, 1954 issue of the Gallatin County Tribune and Belgrade Journal, the International Order of the Odd Fellows (or I.O.O.F.) announced a “Frolic Nite” fundraiser to obtain iron lungs for Montana citizens in need. “The purpose of the Frolic is to raise funds to assist the Grand Lodge of Montana with the purchase of portable iron lungs to be placed conveniently around the state. Arrangements are being made for fast transportation to anywhere the lungs will be needed and they will be available to anyone who is in need of iron lung treatment.”

One Bozeman woman endured severe paralysis after contracting polio. Kathryn Sheila McDonald Johnson was born in Nebraska in 1924 but grew up in the Gallatin Valley and married Warner Johnson in Bozeman in 1935. Warner pursued a career in the Air Force and served overseas while Sheila and the couple’s two children, James and Robert, settled in Nebraska. According to her obituary in the June 13, 1957 issue of the Gallatin County Tribune, Sheila contracted polio in 1952 and spent a year in an army hospital in Denver.

Sheila Johnson was flown back to Bozeman in July 1953, wearing a respirator to help her breathe. As the Bozeman Courier described it, “She is enclosed from her waist to her neck in a Monahan respirator, which forces her chest to expand and contract by forcing in compressed air and pumping it out, enabling her lungs to work.” Once back in Bozeman, the family settled into their home at 321 S. 5th Avenue. Sheila never recovered from her paralysis and passed away four years later from asphyxia due to respiratory paralysis from polio.

Sheila’s obituary stated that she was able to receive treatment at the Northwest Respiratory Center in Seattle, which “improved her condition so she could live for brief periods out of a portable artificial lung. She has been almost completely paralyzed for the past five years, yet has fought a courageous battle against the disease.” Sheila Johnson was named “Montana’s polio mother of the year” in 1956 “for her efforts to overcome the disease and her support of polio campaigns.”

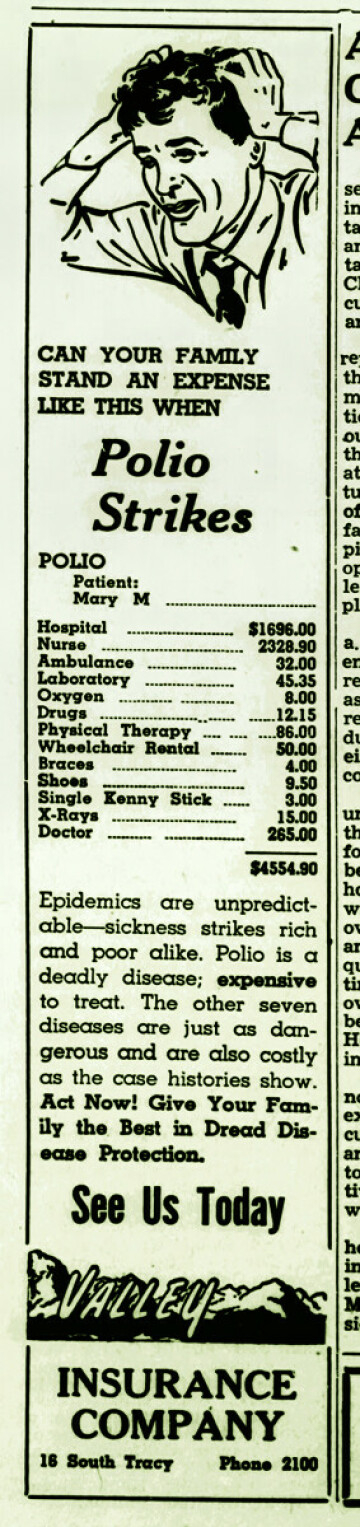

Doctor and hospital bills could add up to a tidy sum, so fundraisers were essential in supporting local families like the Johnsons. In the 1950s, the Bozeman Courier and the Gallatin County Tribune were peppered with articles advertising fundraisers for polio patients and disease treatments. A vast array of clubs, fraternal organizations and other groups joined the effort, including the American Legion, Rebekahs, and the IOOF.

Valley Insurance Company, located on South Tracy Avenue in Bozeman, published advertisements in the Gallatin County Tribune that illustrated the potential cost to families affected by polio. Although the cost of care and treatment depended on many factors and the advertisements were designed to sell insurance, the information gives a picture of the possible financial hardship. A Valley Insurance Company ad published on September 23, 1954, noted a total bill of $4,554.90 for one patient. In today’s dollars, this translates to over $52,000.

In the fall of 1953, Montana was ranked third in the nation for the number of polio cases per 100,000 people, according to a March of Dimes report published in the Bozeman Courier on January 1, 1954. Hope for a solution soon focused on a vaccine. Julius E. Hilgard, state chairman for the March of Dimes remarked; “If the expanded use of this vaccine... verifies the results already obtained, we shall have a weapon that will defeat polio instead of merely holding the line against it.”

Large scale vaccine testing began in the spring of 1954. A Bozeman Courier newspaper report in January explained that the nation was preparing a field trial involving two million children from different counties across the country. Four test counties were in Montana. The Montana State Board of Health and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis chose Missoula, Mineral, Park and Gallatin counties. The Park County News reported on April 1 that 2,200 first, second, and third grade children in Park and Gallatin Counties were eligible to participate in the test. Parents in both counties were provided with information and were required to sign permission forms. The Park County News article, titled “Polio Vaccine for Park, Gallatin Counties, April” explained, “The test involves giving the vaccine to half the children and a neutral control to the others as a means of testing the vaccine over a period of time.”

The Manhattan Inter-Mountain Press gave citizens additional information about the Gallatin County vaccine trial in an April 15 article. “Every child must be vaccinated three times – the first two doses one week apart; the third ‘booster’ dose at least four weeks after the second. The vaccinations will be given in the arm and will be only slightly and temporarily painful.” The article went on to explain that the results of the study and an analysis of the effectiveness of the polio vaccine would not be available until 1955. To answer questions, several doctors spoke with parents and teachers at a series of meetings held at area schools in mid-April. Local doctors Sabo, Pickett, Eneboe, Vadheim and Kearns shared their expertise with the public.

In a Billings Gazette article on April 15, Gallatin County’s Health Director, Dr. Carl W. Hammer, outlined the vaccine schedule. Children in Belgrade and Manhattan were slated for vaccination on April 27, while Bozeman, Three Forks, and rural Gallatin County children would receive their shot on April 28, “if vaccine arrives.” Dr. Hammer explained that the first vaccination would be followed by two additional booster shots, planned for May 5 and June 2. As scheduled, on April 27, 1954, first through third grade students in Belgrade and Manhattan received their first of three shots. The next day, students in Bozeman, Three Forks and Gallatin County rural areas had their turn.

According to a Gallatin County Tribune article published in 1956 summarizing the study in Gallatin County, “983 of the 1,286 eligible children participated” in the trial. Following collection of an initial blood sample, half of the children received the vaccine and the other half received a placebo. The following year, blood samples were again collected from the participating children and analyzed. In the article the city-county health department shared the results: “...the vaccine used in the 1954 field trials neither caused polio nor other major reaction and was 60 to 90 percent effective in preventing paralytic polio.”

Polio fears subsided in the mid 1950s following the successful nationwide Salk vaccine trial and continued immunizations. A 1957 Gallatin County Tribune headline, “Gallatin Licks Polio Danger” reflected public relief. “Gallatin County used to be a critical polio area,” the article read. “The big decrease in polio cases was achieved through the efforts of all the people in Gallatin County.”