A Montana Homestead Hunter’s Toolbox

From Bozeman to Baker and What I Learned Along the Way

What comes to mind with when we hear “homestead”? You probably have a general idea of what they are and when they existed. Covered-wagon times. Settlers and Pioneers. Free land. You might even be thinking of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. You’re on the right track.

But scratching below that surface, unless you are a historian—in particular of the American West—the details begin to fade. Who were the homesteaders and why did they stake their claims? How did they live and where? Did they have any fun or was it all work and no play? Even the descendants of homesteaders only know so much as lore of the short, bygone era was passed from family member to family member with the reliability of the telephone game.

As such a descendant, I recently took a solo trip with my dog to Eastern Montana in search of my family’s homestead. I had been there only once in 1984, when I was too young to remember its precise location or even much about what it looked like except “flat,” like most of the plains area east of the continental divide. All I knew was it was somewhere outside of Baker and that my family was part of a large emigration of Germans to Ukraine (South Russia, then), and from there to Montana and other Western states. They brought the dry-land farming techniques they had perfected and that transformed Ukraine into the “Breadbasket of Europe.”

My homestead hunt was unforgettable. When I returned home to Bozeman, I realized perhaps there must be others in search of their roots, outdoor recreationalists who traverse homestead land to fish, hunt, and watch wildlife, or readers simply interested in those old buildings we see on roadsides and at museums in the West, and the people who inhabited them. So I collected the things I learned along the way, tools I used to uncover the past, a small arsenal I wish I’d had before starting my journey. I put them in a box. Let’s look inside.

Tools of the Past

As time passes, we find that many of our older tools settle to the bottom of the toolbox. These tools are terminology, some of which you are surely familiar with; others arcane, no longer useful in our modern world. Some are essential to a homestead hunt; others anecdotal. Still others are just darn right strange.

Homestead: According to the National Archives, the Homestead Act was passed in 1862 to “accelerate the settlement of the western territory by granting adult heads of families 160 acres of surveyed public land for a minimal filing fee and five years of continuous residence on that land.” Married couples could double their claim to 320 acres; later, single-person claims were enlarged to that amount. Notably, as it was enacted during the Civil War, only citizens who had never fought against the U.S. government could claim under the Act.

Sod hut, sod shanty, sod shack, or simply “soddy”: Some of my favorite homestead structures can be found around Virginia City, on the one-hour drive between Missoula and Garnet Ghost Town, east of Miles City through beautiful prairieland and the striking Strawberry Hill Recreation Area, surrounding Baker and the nearby magical, haunting Medicine Rocks State Park, and on the Pioneer Ranch in Paradise Valley and other areas near Bozeman. They’re just sitting off the road, many of them abandoned, yet somehow preserved, often with turf on top and not bothering anyone, bringing to mind the colloquialism, “They don’t build ’em like they used to.” These architectural wonders were usually one room, no larger than fourteen by eighteen feet, made of board with prairie sod on the roof. Heavy building paper or newspaper may have lined the inside, and each had a cook stove. Framed houses on foundations could also be “sodded up” on the outside or plastered with mud, adobe-style. Regardless of structural path, kerosene lamps or lanterns lit these dwellings. Floors were usually dirt, becoming hard-packed as they were sprinkled with water and walked on. After hardpacking, they were kept meticulously clean.

Shelterbelt: A line of trees or shrubs that served as a windbreak, kept the hut warmer in winter, provided shade in the summer, and reduced erosion. Russian Olive trees and cottonwoods were common. “You could arrive at an accurate estimate of a given family’s income, character[,] and standing in Montana,” wrote Jonathan Raban in Bad Land (1996), “just by looking at their shelter[]belt.”

Cow chips: You already know what these are. Yes, cow dung dried into “chips” or “pies.” Seems like something better left on the prairie as fertilizer, but think about it. Cows eat grass, grass burns. How convenient to have a condensed, partially degraded patty of roughage that burns slowly. As my Great Grandmother wrote in a document I discovered during my hunt, “After [collecting a sack of cow chips], all you needed to have a good fire to cook with was a little paper and a few shavings of wood.”

Boarded-out: Settlers without an immediate water source had to situate themselves near a water table and dig down. This was then “boarded-out” in a box shape with wood boards, and topped with a lid. Water was retrieved by pail. Depending on yield, collected water might be used only for drinking, or occasionally washing your feet. As time went on, however—you guessed it—the boards eventually rotted.

Rocked-out: As a child of the 70s and 80s, I had a glimmer of hope that this term was a precursor to the wonderful music many of us rocked-out to during those decades. Not so here. Wells again. The rotten boards of the homestead well not only caused it to collapse but also resulted in unsavory water. To upgrade, boards were replaced with rock, achieving a more permanent well and tastier water. Homesteaders weren’t head-banging; they “rocked-out” the well.

Socials: Homesteaders utilized most of their free time visiting each other’s spreads. They had dinner, played cards, and when the better homes were raised, they hosted dances. They also participated in “box socials” and “basket socials,” where men and women spent time together and raised money for churches and schools. Boxes, not as big as our toolbox but about the size of a shoe box, or baskets, became mini art projects decorated by the women with tissue, crepe paper, watercolor paint, and ribbons, and included a meal or dessert for two. Men bid on the baskets, and the highest bidder enjoyed the meal with the basket-maker. Things got a little steamier during “shadow socials.” Women stood behind a sheet with a light behind them and, one at a time, stepped close to the sheet and lifted their skirts to the knees. Men bid on the legs. I’m not sure what the highest bidder won but I have an imagination.

Sen-Sen: Boys carried this popular breath freshener in small envelopes to social events, especially dances. They were fragrant, spicy bits that were chewed and shared with dance partners. Sen-Sen might also hide your consumption if you “showed liquor.”

Rabbit drives: This sounds fun. Men would meet, usually at night, form teams, and hunt rabbit on horses with sleds. After the drive, the rabbits were counted and sold at an oyster dinner and party. As a historical book I uncovered stated, even though homesteaders “didn’t have all the material things of life, that so often in society are set up as a guideline for greatness, they did not feel underprivileged.” They “worked hard and played hard.” That appears so.

Tools of the Present

These tools are at the top of our toolbox. They’re lighter, and at our fingertips or inside modern museums.

Montana History Portal (www.mtmemory.org): I wish I had had this invaluable tool, run by the Montana State Library, before I embarked on my hunt. It is searchable by item such as drawing, document, oral history, keywords or exact phrases, and other restrictions such as dates. It has over 40,000 images and 13,000 documents. Try searching your family names or the county where a homestead might be.

GLO Records (www.glorecords.blm.gov): Another remarkable tool is the Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office Records. This searchable database provides access to Federal land conveyance records nationwide, including images of over five million title records from 1788 to present. Of particular use to homestead hunters is the Land Patents search, where you can zero in on state and even county-specific records. With this tool, I found, downloaded, and printed my family’s homestead patent with my Great Grandfather’s name on the deed and signed by President Woodrow Wilson. Enter your family names and see what comes up.

Google Earth, Globe 3D, etc.: You’re probably already familiar with Google Earth and some of the other electronic world maps. There’s no limit as to what can be explored using these tools. You can zoom down to sod huts, old barns, and other structures. As many original homestead buildings no longer exist, look for shelterbelts, water sources, rocked-out wells, or white alkali flats indicating now-dry water tables. Chances are, homesteaders once lived nearby.

Find a Grave (www.findagrave.com): This is what it says it is. A bit of a macabre site, but still a useful tool in tracing family history.

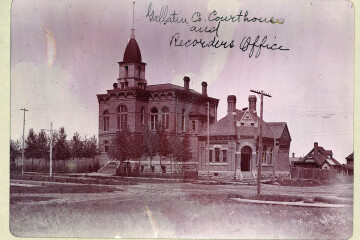

Historical Museums: A visit to your local historical museum may be the most valuable tool in the box. In my case, I fatefully stepped into the O’Fallon Historical Museum in Baker. Whether you have any relation to Fallon County or not, this museum is well worth a visit, complete with an original homestead, jail, two-headed calves, and dinosaur bones. The staff Curator, Melissa Rost, is highly knowledgeable and introduced me to many of the tools I collected during my hunt, including some of the internet databases above and O’Fallon Flashbacks (1975), a history book with family bios and essays, forming the basis of many of my tools of the past and quoted material. I’m forever indebted to her and Mike Madler for directing me to the dirt road that led to my family’s homestead. My hunt and this toolbox would not have been possible without their help.

The Future?

Today sometimes feels like George Orwell’s 1984, very different from the 1984 when I first visited my family’s homestead. Most people know of the popular ancestry websites where you provide a saliva sample. I’m sure those resources are powerful, but I don’t have the guts to send my DNA to Cyberdyne Systems or Skynet. Other genetic tests require blood or hair samples, and now with social media and even car companies collecting biometric data, I wonder if we’re going too far. Maybe AI is already creating profiles of each of us, and our entire family histories will be online and searchable by anyone, anywhere. If AI gains consciousness, who knows what good or bad will come from it.

For now at least, Big Brother is not in our toolbox. And it can never replace those fine sod structures, the open land, and the extraordinary historical museums we have in the West, nor erase the indelible image of the “shadow social.” Next time you’re looking for an adventure—whether in the immediate vicinity of Bozeman, or, as in my case, all the way across the State—grab your toolbox and hit the road. Perhaps you’ll discover that you are the descendant of a homesteader, someone who once chomped Sen-Sen, cooked over cow chips, or won the rabbit drive. Regardless, homesteads are historical marvels that are fun to explore, and might lead you on your own unforgettable journey. Happy hunting.

Michael Carter lives near Four Corners with his family and dog Hubbell. His published fiction, creative non-fiction, and photography can be found at michaelcarter.ink.