Hyalite: 50 Years in the Mountains

Driving to the end of the road and walking off into the mountains is a wonderful thing. I have been doing it for a long time. There is such a sense of freedom, and something else—a bit of daring, as if it might not be quite legal. I mean, there is no charge, it does not cost anything. There are rules, but they are basic; be careful, don’t be stupid, don’t make a mess; if you make a mess, clean it up. Things we learned before we went to school. All that vastness. Free for the experience. Unbelievable. So the first steps are a bit stealthy before the wild thoughts take over.

Often over the years, the location for that drive and walk has been Hyalite. If the Bridgers are Bozeman’s front yard, Hyalite is its backyard. The sense of continuous wilderness is stronger there. It seems to have no limits. In truth, there are trails from Hyalite that could hook one up with the Continental Divide Trail that winds its way to Mexico.

In September 1970, I arrived in Bozeman for the first time. It was snowing. I was a transfer student from the Midwest and, after meeting some others like me, found out we were required to do a week of freshman orientation. Being mostly sophomores and juniors, we considered ourselves so superior that we were surely a different species. We ditched the first week of our new university experience and a few of us plotted how to get to the mountains. I had chosen MSU solely for its location in the Northern Rockies and its proximity to Yellowstone. But none of us had any transportation. We were stuck in dorms, on campus, in town.

Three of us scanned the bulletin board at the SUB and found a club that was planning an outing to Hyalite. We had no clue what Hyalite meant, but knew it was in the mountains south of town. I also have no memory of the identity of the club, but we joined, and showed up after breakfast for the caravan of vehicles heading into the wilderness. The club could have been bird-watching, bible study, or basketmaking, no idea. The schedule for the day included discussions, meetings, contemplative strolls, etc. As soon as the vehicles stopped at the parking area the three of us tore off, running up the nearest peak.

The peak was on the ridge that separates the main Hyalite drainage from the east fork. I think it was the Mummy. We reached the summit, ran down, and showed up at the group spot, tired, scratched, sweaty, triumphant. It had taken most of the day. The executive committee was engaged in a hearing for our expulsion from the club. The punishment was ostracism and no ride home. We stood, heads down, toeing the ground, and accepted our doom. We were not allowed around the fire or any of the snacks. Later, one of the older members hung around after the others drove off and let us load up into the back of his pickup. He may have thought our punishment a bit harsh. I have been to Hyalite hundreds of times since and have always followed the rules and conducted myself accordingly.

Over the years, we have car- and tent-camped at the reservoir, canoed, kayaked, and fished, rented the Window Rock cabin in winter, skied, run and hiked the trails. We have taken many visitors up the Grotto Falls and Palisade Falls trails, and have just generally hung out, soaking up the beauty. But it is my solo trips from the trailheads up to the peaks that stand out in my memory.

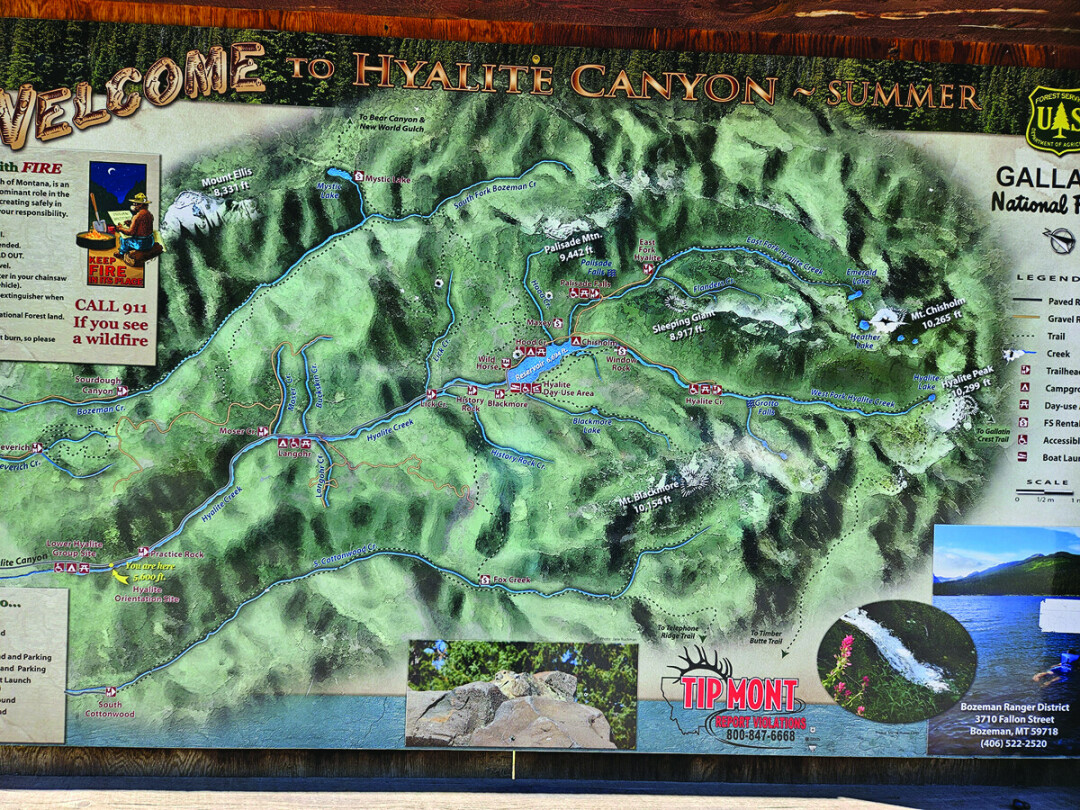

Hyalite Canyon lies close to 20 miles south of Bozeman. The drive along the creek is amazing itself, the wild portent of things to come. The creek has been dammed and the reservoir provides the city with the majority of our water. There are several canyons that lead up into horseshoe shaped ridges of high peaks. At the head of the canyons, glacial cirques hold gemlike lakes and ponds. The forest is mostly fir and lodgepole pine up to timberline. There are good, well-maintained trails leading up into these canyons. The slopes and canyon walls contain dramatic waterfalls, solid in winter for world-class ice climbing.

My method was to drive to a trailhead on Friday night, walk up until dark, camp wherever I was, wake in the morning and find a way up to a ridge. Once on top, I would glide along, summiting peaks and trying to put together traverses to other ridges. Then, I would camp on Saturday night and in the morning find my way down and back to the trailhead. My objective was to climb all of the 10,000-foot peaks, then the 9000-foot ones, then repeat. I have lost track of the repetitions over the decades and have never tired of the game. Gotta lotta stories.

The maintained trails extend to the summit of Mt Blackmore in the west, and Hyalite Peak in the center of the range. It is rare to complete a solitary hike up either one of those mountains. Chatting with like-minded people outdoors is a big part of the attraction. The rest of the peaks and ridges are tough to access up steep slopes. On those treks, company is sparse.

I have encountered people who have hiked to Everest Base Camp, and people who are not hikers at all, but set out on a trail and were drawn into the mountains by their beauty. I have spent bluebird cloudless days. I have been battered by wild storms. I have found some specimens of Hyalite minerals. There have been days when I ran around from dawn to dusk, never resting. There have been days when I arrived at a spot at timberline, made camp and a little stick fire and spent the day contemplating. Some of the peaks have registers. When I reached the most remote ones, the BWAGS (Bozeman Women’s Activity Group) had always been there before me.

On a trip a few years ago, I arrived at the saddle after summiting Mt Blackmore. There was a couple there looking at their map. I said ‘Hi,’ and they asked me how to get to Hyalite Peak. I said that they were miles away on the wrong trail, and in the wrong drainage. They replied that a friend had gotten there from where we were and had told them to try. I said, ‘Wow,’ and began to put the ridges together in my mind. We consulted the map and I wished them luck. I don’t know if they made the trek, but the next year I managed it. This happened at a point when I did not think there was anything new left for me in Hyalite. Wilderness is like that, always new ideas, new challenges.

Of course, Hyalite Canyon has changed much since my first 1970 trip. The dam has been raised, providing better water supply and control, but flooding some of our old go-to campsites. The dirt road has been paved, even plowed in winter to provide access to ice climbers, skiers, and fishermen. Camping at Hyalite is not a spur of the moment decision; it now requires reservations online. It is a very busy place. Yet the essence of it is the same. The peaks above the lake, the clouds above the peaks, the impatient rushing water in falls and streams. The crowds are happy, and active; the vibe is all about fun and recreation. To reach solitude, go farther into the forest, up to the high country. Drive in early when the rising sun illuminates the hills west of the reservoir. Stay late when the low light lights up the central rock spires. Go there when the weather threatens and witness the power of a thunderstorm or the quiet fall of an afternoon snow. There is a lot of room there and no need to worry about anything other than ‘Did we pack the cooler?’ and ‘Are my hiking boots in the trunk?’

I have a ritual I try to perform each year. I call it First Camp and End Camp. Dates and places vary but there was a time when Hyalite was the likely location for both. The first time out in the spring and the last trip in the fall. Both are usually weather challenged. In this century we have social media platforms to commemorate our lives. But previously it was all interior. Mindful.

I have a vivid memory of a late October night that puts me at Hood Creek campground on a hill above Hyalite Reservoir with no one else around for miles. No moon, no stars, just wind and swirling clouds. Weather sure to break, snow soon to fall. A fire, a chair, a couple of coats and a wool blanket. Thoughts of all the years in that special place up to then. Plans for the next time.