The Hole in the Wall

Attempting to Solve a Historical Mystery

The old 1911 Gallatin County Jail on Main Street is full of secrets. During its seventy-year use, the castle-like structure housed thousands of unwilling occupants during some of the grimmest times of their lives. When prisoners were relocated to a new facility in 1982, the Gallatin Historical Society transformed the space into a local history museum, taking care to preserve elements of the jail and its history. Today, museum staff continue to make new discoveries about the building and the events that make up its fascinating past. Meticulous research has uncovered the truth behind some of the building’s legendary stories, but some remain a mystery. One of these is the infamous 1940s jail escape attempt.

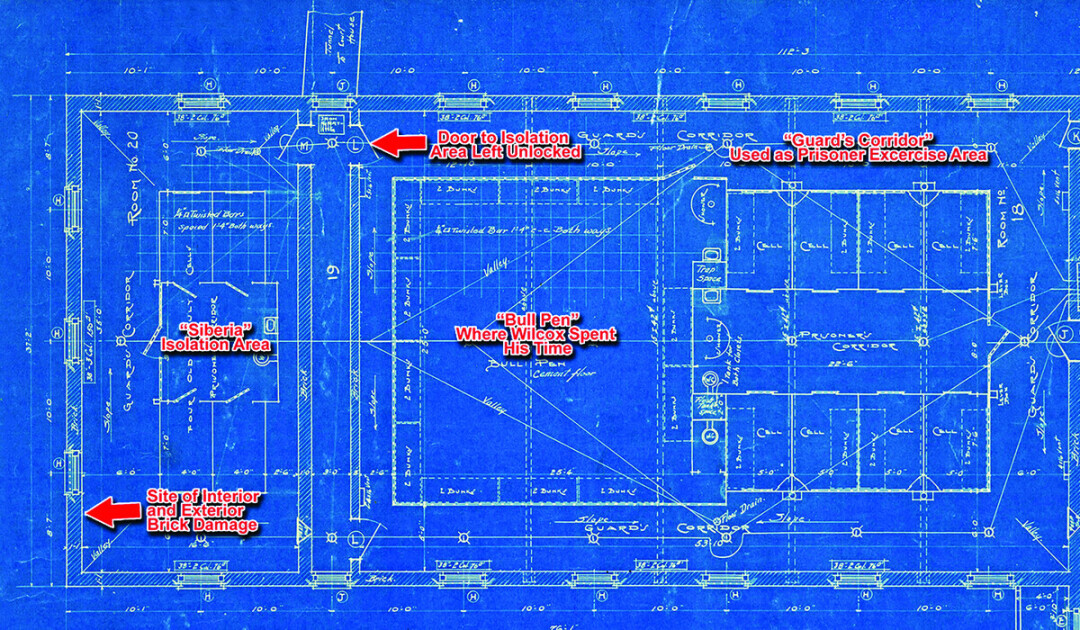

Today, a portion of what was once the isolation area of the jail, nicknamed “Siberia,” is preserved in the northwest corner of the museum. Marked on the wall is a grouping of bricks highlighted with bright paint. This 3’4” x 4’7” area has always been specially noted. When the author of this article first joined the staff of the museum sixteen years ago, the bricks were outlined in black. In recent years, they have been carefully painted red to set them apart from the rest of the whitewashed bricks.

According to legend, in the mid-1940s two prisoners occupying the isolation area at the rear of the building made a valiant and creative attempt to break free. In his 1987 booklet Law and Order in Gallatin County: Jails, Courthouses, Detention Centers, and Terminal Justice, Montana historian and MSU professor Merrill Burlingame described the event this way: “They [the prisoners] proceeded to appropriate a thin mattress, soak it with water and prop it against the north brick wall with the hope of softening the friable Bozeman cement filler. Their hopes rose after a night or two of this treatment when the cement did soften somewhat.”

The story goes on to note that the pair, breaking through the first masonry layer, managed to access the next brick wall in the multi-tiered bastion. Eventually, they pierced the exterior wall and, seeing daylight, the prisoners were hopeful their labors would finally pay off. Unfortunately for them, law enforcement personnel walking behind the building spotted the hole before it was big enough for the inmates to squeeze through. To this day, when one walks along the north side of the building’s exterior, it is easy to spot a small brick repair job. Ten bricks of a slightly darker red than the rest are clearly visible near the northwest corner of the building.

Plainly, something happened at this location to warrant the repair. What is unclear is how much of this “soaking wet mattress” story is true. Over the years, museum staff and volunteers have worked to uncover any additional evidence that could corroborate the legend. Several searches in 1940s newspapers have to date failed to uncover any official description of the above-mentioned events.

However, there is a newspaper account of an intriguing escape attempt that transpired in 1933. In August, a young man named Edward M. Wilcox was booked into the Gallatin County Jail on rape charges. In the prisoner register book, the twenty-year-old Wilcox was described as five feet nine inches tall with blue eyes and brown hair. The ledger records that he was arrested on a warrant, booked into the Gallatin County Jail on August 19, 1933, and held until November 16, 1933, when he was released following a trial and acquittal.

A search of local newspapers uncovered further details. Wilcox was arrested following an incident in which a 15-year-old girl was assaulted near a service station at Main St. and 7th Ave. An account of the trial and acquittal, published in the November 16, 1933 issue of the Bozeman Weekly Chronicle, suggests there was some confusion about the identity of the assailant, and ultimately the victim testified that Wilcox was not the culprit. Wilcox was released on November 16 after three months behind bars. His escape attempt a month earlier, though mentioned at the trial, appeared to not have affected the decision to release him.

Waiting in jail for his November court date was apparently unbearable for Wilcox. After a month of incarceration, he panicked. On September 21, 1933, a Bozeman Weekly Chronicle article headline announced, “Wilcox Tries to Break Jail: Youth Held for Rape Foiled in Attempt to Dig Way Out. He Was Doing It For His Mother.” According to the article, Wilcox confessed his plan to the Sheriff following discovery of his activities: “‘I was doing it for my mother. It would break her heart if I was sent to prison. I was going to dig the hole and leave it covered up until after my trial, then if I was convicted, I was going out through the hole.’”

The newspaper account reports Wilcox began chipping away at the brick wall after 6 o’clock a.m. on the morning of Sunday, September 17. That morning, Wilcox and fellow prisoners in the “bull pen” area of the jail were released from their confines to walk around the inside corridor and stretch their legs. Wilcox took advantage of the situation and brought a screwdriver with him, which he claimed had been given to the prisoners in the bull pen to repair a stove.

The Chronicle article briefly described the location Wilcox chose for demolition: “At 9 [a.m.] when Sheriff Westlake went back into the jail yard, he could not locate Wilcox, and finally discovered him in the rear compartment of the jail, which is partitioned off from the rest. The door to the rear room, used for solitary confinement, had been inadvertently left unlocked.” The Chronicle also noted that “a jail mattress hung from a windowsill,” covering the hole and serving as a screen that Wilcox “hoped would hide his operations from the eyes of authorities until he had completed his task.” To get a clear picture of this situation, it is helpful to know something of the old Gallatin County Jail’s history, design and features.

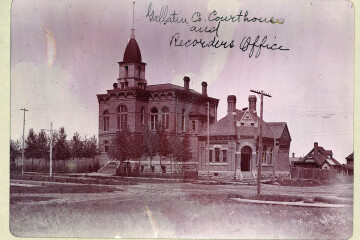

Prior to construction of the 1911 jail, county prisoners occupied cells in the basement of the old 1880 courthouse building on the northwest corner of Main St. And 5th Ave., where the current courthouse sits today. This basement jail was dank, smelly, and described as a “pest house” in a 1908 Republican-Courier newspaper article, but it did have a small outdoor exercise yard surrounded by a brick wall. When the new 1911 jail was completed, no outdoor exercise yard was added. A March 14, 1911 Republican-Courier article describing the new jail’s layout includes only one small statement about prisoner exercise: “Each apartment [section of the jail] has exercise corridors and in the ends of these the plumbing fixtures will be grouped.” An examination of the building’s original blueprints reveals these “exercise corridors” were small, included bathroom fixtures, and ranged in size from 81 to 180 square feet. The large group holding cell called the “bull pen” had a common area of about 625 square feet.

The 1933 article detailing Wilcox’s escape attempt claims the prisoners were given the opportunity that morning to wander around the guard’s corridor for their morning exercise. The term “jail yard” used to describe where Sheriff Westlake caught Wilcox digging does not refer to an outdoor area, but to the interior guard’s corridors. It is understandable that jailers would have allowed prisoners greater freedom to wander the halls for limited periods of time. The corridor was secure, and access was restricted to the more secluded rear portion of the building that housed the isolation cells. Or so they thought.

Wilcox got lucky that morning in September and took advantage of the unlocked door to the isolation cell wing. The blueprints reveal that there was one set of double doors accessing the isolation area, located at the end of the guard’s corridor on the east side of the jail. While the Bozeman Weekly Chronicle article describing the escape attempt does not specify exactly where Wilcox was chipping at the wall, it is reasonable to assume he would have chosen a location farthest from the door and hidden by the cells in the center of the room. If this hypothesis is correct, an ideal spot would have been the extreme northwest corner of the building. This is precisely where the interior marked bricks, as well as the exterior repair patch, can be seen today. Interestingly, the September 21 Chronicle article detailing Wilcox’s escape attempt suggests he was only able to break through the first brick layer before capture. “Two of the three layers of bricks which comprise the wall of the jail still were between him and freedom when his attempt was discovered.”

Obviously, this author cannot say with any certainty that Wilcox’s digging in 1933 solves the mystery of the Siberia escape attempt legend that has been a part of museum lore for decades. There are still details that need to be solved, such as why an exterior repair was necessary if Wilcox only damaged the inside wall. It is interesting to speculate – to take the time to put oneself in another’s shoes and consider what one would do in similar circumstances. Part of the fun of historical research is the attempt to sort out the mysteries of the past.