Happy Birthday Bozeman

Summer 2014 marks Bozeman’s 150th birthday, also known as a sesquicentennial

As the Civil War raged in the East, pioneers began developing the American West. Gold strikes attracted miners, merchants and fortune seekers to southwest Montana in the early 1860’s. In 1862, miners in Idaho Territory traversed the Bitterroot Mountains via Lolo Pass and found gold in Grasshopper Creek, around which they developed the village of Bannack. The nearest seat of government was located a hard week’s travel away, where the Clearwater River emptied into the Snake River in the town of Lewiston. In an effort to bring law and order to the area, settlers successfully petitioned the federal government to create Montana Territory, with the territorial capital in Bannack, in 1864.

Travel to Montana Territory’s gold fields proved an arduous undertaking. There were three options in the years before a transcontinental railroad. An emigrant could travel overland on the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall, in the vicinity of present day Pocatello, Idaho, and then turn north. Others travelled up the Columbia and Snake Rivers and crossed the Bitterroot Mountains at Lolo Pass or followed the Mullan Road from Fort Walla Walla, Washington Territory, to the interior of Montana. Steamboats brought passengers up the Missouri River to the end of navigation at Fort Benton, Montana, after which passengers disembarked for 200 mile overland trip to the diggings in the south.

Miners trekked the region in search of new gold strikes. In the spring of 1863, a group of men found a gold deposit in Alder Creek, about 80 miles east of Bannack. Thousands of fortune seekers swarmed Alder Gulch and within weeks the villages of Nevada City, Virginia City, Summit, Highland and Adobe sprung up. In response to the population boom, the territorial capital moved to Virginia City in 1865.

Daniel Rouse, arrived in Montana Territory by way of Idaho Territory in 1863. Rouse, who started and then abandoned farms in Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Iowa, ventured west to join the Colorado gold rush. Reports of the new diggings in Bannack persuaded him to abandon plans to travel to California and try Montana Territory instead.

Rouse met William Beall (1834-1903), in Virginia City in 1863. A Pennsylvanian with training in architecture and engineering, Beall had a farming background and recognized the profit to be made by growing and selling foodstuffs to hungry miners. The two joined a group of men who founded Gallatin City, where the Gallatin, Madison and Jefferson Rivers come together to form the Missouri River, in 1863. Beall was selling potatoes in Virginia City when he first spoke with Daniel Rouse and John Bozeman about founding a town upstream from Gallatin City, on the East Gallatin River.

John Bozeman (1835-1867), left his wife and three daughters in Pickens County, Georgia in 1858 to participate in the Colorado gold rush. He arrived in Bannack in 1862 and moved to Virginia City in early 1863. Bozeman recognized the need for more direct transportation to Montana Territory’s gold fields and agricultural production to feed the region’s rapidly expanding population.

Working with John Jacobs, Bozeman spent the summer of 1863 exploring an overland cutoff route that would enable wagons to leave the Oregon Trail near what is now Glenrock, Wyoming, and travel north between the Big Horn Mountains and the Black Hills to the Yellowstone River. The route then took travelers up the Yellowstone River and over what is now Bozeman Pass, then across the southern Gallatin Valley and up the Madison River and over a last pass into Virginia City. The route violated the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, which promised the Sioux and Cheyenne the area between the Big Horn Mountains and Black Hills as a reserved hunting ground. The route also cut south of Gallatin City, which combined with the mosquitoes, lead to abandonment of the village in the 1870’s. Bozeman lead the first wagon train over this route in the late summer of 1863.

Over the winter, Rouse, Beall and Bozeman hatched a plan to found a town along the new route where merchants could profit by resupplying travelers using the new cut-off route. In the spring of 1864, Bozeman and Jacobs went east to guide another wagon train across what was becoming known as the Bozeman Trail or Bozeman Cut-off. Beall and Rouse reconnoitered the area of the East Gallatin River in search of a suitable town site along the wagon road. They selected a flat spot where the Bozeman Trail crossed a quickly moving creek, about 65 miles east of Virginia City, in early July 1864. They chose the site for its proximity to rich farmland and potential use of the creek to drive lumber and grain mills.

Beall, Rouse and Bozeman established land claims under the Land Exemption Act of 1841. Beall and Rouse were 30 years old, and Bozeman 29. As with its descendent the Homestead Act, this legislation enabled American settlers to claim up to 160 acres of public land. Squatters had to stake out the property, improve the land and actively live on the land for at least 14 months, after which they could purchase the property for not less than $1.25 per acre.

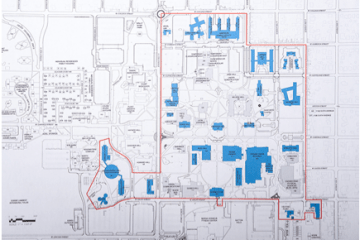

Beall used his engineering skills to lay out a town plat three blocks from east to west and three and a half blocks from north to south. He surveyed and staked out a 93 foot wide Main Street running east to west where the Bozeman Trail went through the town site. One block south of Main Street was Babcock Street, named for William Babcock, who arrived in Montana Territory via the Mullan Road from Walla Walla, and came to Bozeman from Virginia City in July 1864. South of Babcock Street was John Bozeman’s claim. North of Main Street, Beall laid out Mendenhall and Lamme Streets, also named for early settlers. A half block separated Lamme Street from Beall Street, north of which was Beall’s land claim.

From east to west, Beall’s plat created three city blocks, with the western two blocks roughly the same size and the third eastern block a double length where what is now Bozeman Creek ran through the town site. Rouse’s land claim lay to the south east of the town site, along what is now South Church Avenue.

Brothers William and John Alderson arrived at the townsite in the middle of July 1864, where they found Rouse and Beall busy hauling logs to construct cabins on their land claims. After deciding to abandon their plans to mine for gold, the Alderson’s took up land claims on the hill to the south of Main Street with plans to establish a dairy.

Bozeman guided a wagon train through the area en route to Virginia City about the first of August and quickly returned to the upper East Gallatin. He was present when Alderson, Rouse, Beall and others formed a land claim association for the town site in August 1864. Early settlers in the American West established claim clubs in an effort to fairly govern the division of frontier lands before the government land survey occurred. At a meeting of the claim association on August 9, 1864, William Alderson motioned that the town site be named “Bozeman,” in recognition of all John Bozeman had done to develop the new cut off route and town site.

On September 17, 1864, the Montana Post, the newspaper printed in Virginia City, published a letter from John Bozeman promoting settlement of the town site and the Gallatin Valley. Bozeman described the town as, “located on a handsome and level piece of land, in what is called the upper valley, where the Bozeman cut-off or route to the Eastern States crosses the little Gallatin.” He described how he, Rouse and Beall were inducing settlement of the town site, “The proprietors offer liberal donations in town lots to builders in the village, and there are several new structures now going up.” Bozeman also described how the nearby creek would be used to power industry, “A saw mill and grist mill are to be built next summer, within a mile of the village, and, as demands may require, other mills and machinery will be erected, the valley abounding in water-falls suitable for the supply of motive power.”

Bozeman recommended that men looking to establish farms would, “find it to their advantage to settle in the great Gallatin Valley.” He described the abundance of creeks and springs in the area, which afforded water for stock, domestic use and irrigation of crops. He may have stretched the truth a bit when he wrote, “The farmers who have resided in Gallatin valley for one or two years, say the winters are as mild as those of the Middle States…In point of fact, Gallatin valley is the oasis of the mountains.”

The same Montana Post publication, and those throughout the following year, describe the growing use of the Bozeman Trail which ratcheted up tension between emigrants and Native American tribes in the area. Use of the Bozeman Trail grew over the following year when the end of the Civil War enabled the US Army to establish protective forts along the trail in 1866. Despite the Army’s presence, the route earned the nickname “the Bloody Bozeman.”

The year 1867 was a turning point in the fledgling community’s history. John Bozeman was killed under dubious circumstances in April 1867, as he journeyed east to establish flour delivery contracts with the Army forts along the Bozeman Trail. Bozeman’s murder lead to hysteria of Indian attacks, especially when combined with Red Cloud’s War.

To protect the town, the Army established Fort Ellis three miles east of Bozeman, in August 1867. The Army outpost played a vital role in stabilizing the town’s economy. Local entrepreneurs like Nelson Story and William Alderson supplied the Army with flour and beef, and soldiers spent their pay in the town’s businesses.