Bozeman’s Historic Trolley Car System

and Montana’s First Interurban Electric Railway

With the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883 progressive Bozemanites began to cast off what they considered rural or uncultured in favor of more urban and upscale living. Log cabins were torn down and were replaced with architecturally designed brick homes. One by one, impressive masonry buildings, like the original County Courthouse (1880-81), the Masonic Lodge (1882-83), the City Hall and Opera House (1890), St James Episcopal Church (1890), the Bozeman Hotel (1891) and the Northern Pacific Depot (1892) refined the urban landscape in a time when native peoples still roamed their diminishing world and Montana was evolving from a territory into statehood (1889).

Bozeman’s 1889-1892 bid to become the capitol was a catalyst for much of the newer amenities, including a highly functional and efficient electric-street car system that began operations July 27 1892. Reliable electricity generation from Bozeman Creek a year earlier, not only helped replace the gas lamps on Main Street at Tracy, Bozeman and Rouse Avenues but now were helping transport travelers from the Northern Pacific Railway Station at 820 Front Street via North Ida Avenue to Peach Street, North Church Avenue, to Main Street ending at Grand Avenue, a total of 1.3 miles in the comfort of one of three trolley cars Gallatin Light, Power and Electric were operating.

Construction immediately continued to extend the network an additional 1.2 miles to the recently-established Montana State College via Main Street and South Ninth Avenue to a terminus at West Cleveland Street. In 1901 under the ownership of Bozeman Street Railway Company an extension of 1.28 miles was added from Grand Avenue and Main via South Grand Avenue, West Alderson Street, and South Seventh Avenue to Garfield Street, terminating in front of Montana Hall on the college campus.

Through personal accounts and newspaper articles, one particular motorman was often mentioned. Larry O’Bryne, an Irishman, took a personal interest in his customers and their well-being. He was known to go to residence’s doors to wake them up if they had a train connection to make or a class to be taught. During a house fire close to campus, neighbors on Grand heard the clatter of Larry and his trolley pulling the fire department hose car, which was the quickest way for it to get there, but it was too late for the house.

The local trolley system played an important role in shaping local settlement patterns and was particularly beneficial for women’s mobility by providing safe and socially acceptable transportation. As highlighted in the tour book, Bozeman Women Heritage Trail, local historians identify several prominent single women who worked on campus or elsewhere and lived along the streetcar route up South Grand Avenue.

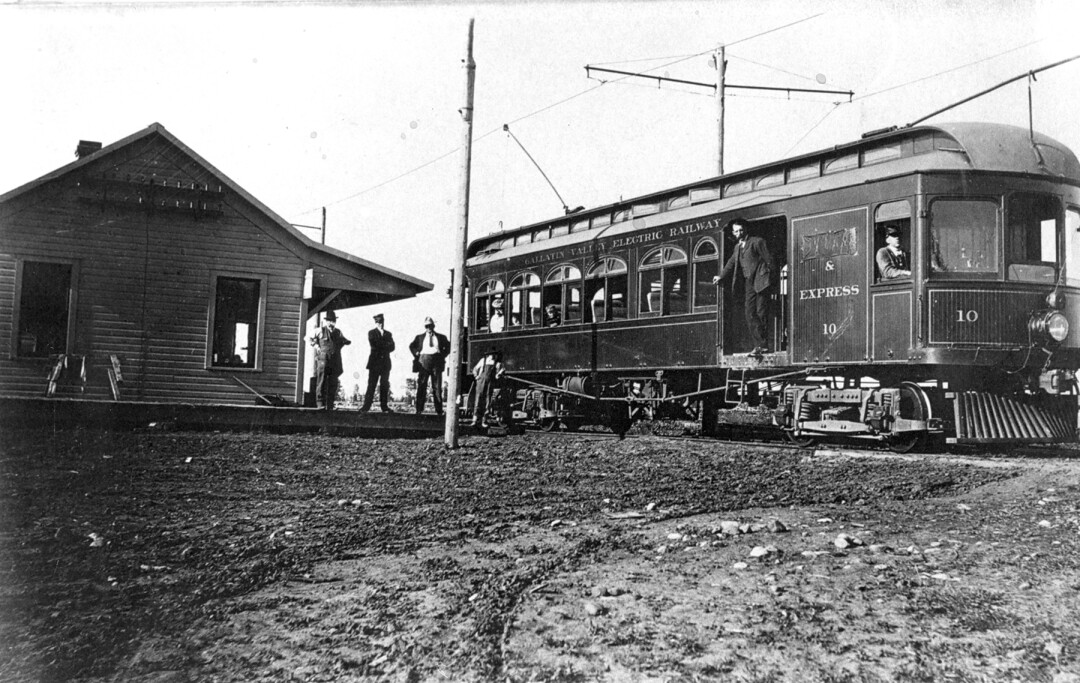

With the success and popularity of Bozeman’s trolley system as being a useful and efficient means of travel by 1907 valley farmers started talking about the possibility of an electric railway extending to the lower Gallatin Valley to connect with Bozeman. The possibility for both passenger service as well as the ability to increase freighting options ignited a spark amongst valley farmers and ranchers and by October of 1907 they had raised $50,000 for the project. By March of 1908, after raising another $100,000, the Gallatin Valley Electric Railway Company was capitalized and “was ready to make dirt fly.” Thus the beginning of Montana’s only interurban electric railroad system.

The line would run west from Bozeman, then south to Salesville, (Gallatin Gateway), a distance of 17 miles with stops along the way that included, the Patterson Ranch (South 19th and Goldenstein), Ferris Hot Springs (formerly Jerry Matthew’s Hot Springs and currently Bozeman Hot Springs south of Four Corners), Balmont, Chapman, Potter, Blackwood, Gilroy and Atkins.

On April 27 1909, the Avant Courier reported, “At last the first sod has been turned and the actual construction work of the Gallatin Valley Electric Railway has been started. Within the next six months the activities in this valley will be without precedent and when the leaves begin to fall again the handsome passenger cars and the long freight trains laden with the produce of the valley will be spinning over the shining rails bringing prosperity and good cheer to the ranchers and villagers along the route.” The May 9 1909 issue followed up with the report that “The work of constructing the new interurban electric line goes merrily on, progress made during the past week is a little short of astonishing.”

Locals were proud of the railway, and as the Avant Courier predicted the workers had completed the GVER to Ferris Hot Springs and Salesville by mid-September. In the first day of operation 200,000 pounds of barley for the Bozeman Brewing Company were delivered, and in the first month over 3,000 passengers enjoyed the ease of traveling for school, work, and social events.

The Ferris Hot Springs was a deserted health resort that was lapsing into nothingness but the electric railway and the visitors that paid 50 cents for roundtrip transportation changed all that.

A year later, without much fanfare, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St Paul Railroad moved in to buy the entire stock of the little interurban and Bozeman’s streetcar lines; at the same time, they announced plans to extend the rails from Ferris Hot Springs to Three Forks, where it’s main line stood ready to receive goods from the Gallatin Valley.

When the influenza epidemic of 1918 hit the valley the interurban car served as an ambulance transporting many people to the emergency hospitals. Some never came back.

Trolley cars serviced Bozeman residents and visitors for two and a half decades, but with the growing popularity of automobiles and World War I, three trolley cars were reduced to one. Early in the morning on December 15, 1921 snow began falling on the city. As the day progressed the lone trolley tried to keep the tracks open but the drifts were too high and the car was damaged from bucking the heavy snow. This last damaged trolley was sent to Deer Lodge for repairs and by spring it became clear that the trolley company had no intention of resuming service. The Milwaukee Railroad officials offered to give the entire street railway system to the city, “with a new car thrown in” if Bozeman would operate the line and absolve the railroad company of any responsibility for its upkeep. The City declined and soon after the railroad company took up its tracks and placed the affected streets in “first class condition”. An interurban combo known as the Gallagator continued to make runs between Bozeman and Gallatin Gateway and Three Forks and Gallatin Gateway until 1930.

In 1927 The Milwaukee built the Gallatin Gateway Inn to serve its passengers bound for Yellowstone National Park. The Milwaukee brought tourists there by rail from the main line at Three Forks, then bussed them through the scenic Gallatin Canyon and 75 miles south to Yellowstone. While a great idea the overall timing was bad, within ten years tourists were traveling to Yellowstone by automobiles, not trains.

From the memoirs of Paul Busch, the first motorman on the GVER, “We were more than a transportation service. Everyone in that area knew us and we knew them. When a farmer was unable to get into town to buy a small machine or match a piece of cloth we would fill his order on our run into Bozeman. One day someone wanted a morning paper delivered at his farmhouse, and soon I was throwing two dozen or so papers a day along the line. I became expert at hitting the mark as we rolled by at 30 or 40 miles per hour.” Paul and his conductor Doc Barclay and later John Null initially provided four trips a day, but with the gradual increase in automobiles, those trips were reduced to two and in later years Paul would state that the car “became a glorified school bus with only a few adults”. In 1930 it was decided to discontinue the passenger car, and the day after school ended so did the passenger interurban trolley service.

The June 1, 1930 train schedule listed freight service only and the final wires were pulled down in Bozeman and a steam locomotive was brought in to replace the electric freight car.

Thus marked the end of an era, for almost four decades both the urban and the rural residents benefitted socially, educationally and financially by imagining and building an electric trolley and interurban transportation system based on the needs of our community.