Put A Little Gravel in Your Travel

Day Trips Steeped in History

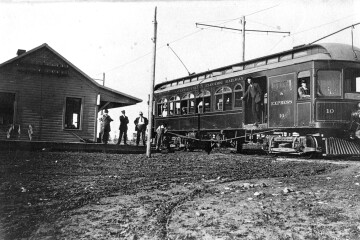

Did you know the little Montana town of Ringling was named after the world-famous circus family, the Ringling Brothers? Or that one of the brothers, John, who was one of the richest men in America in the early 1900s, started a ranching empire there, built a grandly named short-line railroad, dabbled in White Sulphur Spring’s famous waters, and took local black musician Taylor Gordan on trips around the country?

Smart and shrewd—some would say “scheming”—John rubbed some people the wrong way. One local businessman claimed, “There were crooks and crooks and there was John Ringling, the master-minded crook of the ages.”

Richard Ringling followed his uncle to Montana and, when he wasn’t helping run the circus, expanded the family’s agricultural operations. He raised hundreds of thousands of cattle and sheep on far-flung ranches, built a state-of-the art dairy farm, launched a cannery for sweet peas in the Bozeman area, and was a founder of the Bozeman Roundup, a multi-day rodeo extravaganza.

Richard loved the cowboy way. He sponsored The Association of American Cowboys and shipped rodeo stock to Madison Square Garden and other venues. But still drawing on his family’s world-wide business, Richard sometimes used old circus tents as temporary ranch buildings.

Later, Richard’s son Paul continued the ranching dynasty and became a state legislator.

In all, the three Ringlings created an intriguing and amusing history that is finally chronicled in a new book, “Three Ringlings in Montana: From Circus Trains to Cattle Ranches,” by author and historian Lee Rostad.

After several devastating fires, the last in 1931, and the demise of the railroads Ringling dwindled to a few people and the surrounding ranches. Today it has a post office, school, and restaurant and bar.

The town was immortalized by Jimmy Buffet when he wrote of the town in his song Ringling, Ringling on the Living and Dying in Three Quarter Time album. And yes, Livingston Saturday Night was about Livingston, Montana.

This leisurely 190 mile drive from Bozeman takes you on a breathtaking trip through the mountains and eventually through some of the best farmland and ranches in Montana. This area is also steeped in history, taking you to important spots along Lewis and Clark’s expedition.

Bozeman to Livingston (22 miles) - Take Interstate 90 east until you see exit signs for Livingston. Here you’ll find good places to eat, shop and experience the town’s once thriving railroad.

Livingston to Clyde Park (20 miles) - Jump back on I-90 and take that to Highway 89. Head north to Clyde Park, a small town that revolves around ranching and farming.

Clyde Park to Ringling (30 miles) - Stay on Highway 89 north and you will reach Shields River Valley, an integral stop during Lewis and Clark’s journey. Continue north on Highway 89, past breathtaking views of the Crazy Mountains, until you reach Ringling, a town named after one of the famed circus Ringling Brothers.

Ringling to Townsend (42 miles) - Get back on Highway 89 to Highway 12. Head west to Townsend. From here, you’ll have easy access to the Elkhorn and Big Belt Mountains.

Townsend to Missouri Headwaters State Park (32 miles) - Take 287 south until you see signs for the State Park. This is where the Gallatin, Jefferson and Madison Rivers converge to form the Missouri.

Missouri Headwaters State Park to Three Forks (5 miles) - From the State Park, jump back onto 287 to Three Forks. Three Forks offers a mixture of both great fishing and rich history.

Three Forks to Bozeman (32 miles) - Take Interstate 90 east and head back to town.

Earthquake Lake

At 11:37 PM on Monday, August 17, 1959, one of the severest earthquakes recorded on the North American continent shook this area. It sent gigantic tidal waves surging down the 7-mile length of Hebgen Lake, throwing an enormous quantity of water over the top of Hebgen Dam, the way you can slosh water out of a dishpan, still keeping it upright. This water, described as a wall 20 feet high, swept down the narrow Madison Canyon, full of campers and vacationers who were staying in dude ranches and at three Forest Service campgrounds along the seven-mile stretch from the dam to the point where the canyon opened up into rolling wheat and grazing land. Just about the time this surge of water reached the mouth of the canyon, half of a 7600 foot high mountain came crashing down into the valley and cascaded, like water, up the opposite canyon wall, hurtling house-size quartzite and dolomite boulders onto the lower portion of Rock Creek Campground.

The slide dammed the river and forced the surging water, carrying trees, mud and debris, back into the campground. The campers who’d escaped being crushed under part of the 44 million cubic yards of rock found themselves picked up and thrown against trees, cars, and trailers. Cars were tossed 40 feet and smashed against trees by the force of the ricocheting water and the near-hurricane velocity wind created by the mountainfall. Other cars were scrunched to suitcase thickness and thrown out from under the slide.

“The Night the Mountain Fell: The Story of the Montana-Yellowstone Earthquake” by Edmund Christopherson was originally published in 1962 and has been reprinted as well as available for Kindle. Another great take along book is “Shaken in the Night: A Survivor’s Story from the Yellowstone Earthquake of 1959” by Anita Painter Thon. Anita’s personal account of this night is a frightening and tragic story of panic, horror, and courage in the face of disaster. It is also a reminder of the human spirit’s resilience and selflessness, as perfect strangers unite to save lives, even at the risk of their own. Life is a fragile miracle, and Anita reminds us to cherish every day and treat it like the gift that it is, lest we’re ever shaken in the night.

In this 240 mile day trip from Bozeman through the Madison Valley, you’ll find a wide variety of things to see and do. There are spectacular views of the mountains and lush valleys, as well as small town shopping opportunities in Ennis and plenty of fishing accesses to wet a line.

Bozeman to Norris (38 miles) - Head west down Highway 84 until you reach the town of Norris, an old gold mining town now known for its hot springs.

Norris to Ennis (16 miles) - From Norris, turn south on Highway 287 until you see signs for Ennis. Ennis is the self-proclaimed “Flyfishing Capital of the World.”

Ennis to Quake Lake (43 miles) - Continue south on Highway 287 to Quake Lake. This unique lake was formed by an earthquake in 1959 and reaches depths of up to 180 feet.

Quake Lake to Hebgen Lake (12 miles) - From Quake Lake, continue east on Highway 287 until you reach Hebgen Lake, which is considered to have some of the best dry fly-fishing in the state.

Hebgen Lake to West Yellowstone- (31 miles) Continue on Highway 287 to the Highway 191 junction. Head south until you reach West Yellowstone, a bustling little town and one of the main entrances to Yellowstone National Park.

West Yellowstone to Big Sky (48 miles) - Travel north on Highway 191 until you reach Big Sky. From here, take Highway 64 to Big Sky Resort, one of Montana’s premiere ski destinations.

Big Sky to Bozeman (49 miles) - Come back down Highway 64 to Highway 191 North. Enjoy the scenic drive through Gallatin Canyon and along the Gallatin River until you reach Four Corners, 30 miles down the road. Turn right onto Huffine Lane and continue east for six miles until you get back to Bozeman.

Lewis and Clark Caverns

Native Americans have known about the caverns for hundreds of years, and they are mentioned in Indian stories. Although the caverns are now named for Lewis and Clark, they never visited them, nor is it likely that they knew of them.

Charles Brooke and Mexican John, both from Whitehall, discovered the cave entrance in 1882. They had heard of the great caves from local Indian legend and set out to look for them. They did not tell many people about their discovery.

In 1892, two hunters, Tom Williams and Burt Pannell, discovered the cave entrance when they noticed a plume of steam coming out of the cave. Tom Williams wanted to explore the caverns and six years later, he finally did. Using ropes to rappel and candles for lighting, they lowered themselves down into “Discovery Hole,” a deep cavity.

Williams soon convinced local investor, Dan Morrison to partner with him to develop the cavern for tours and named the site Morrison Cavern. They were successful in developing and promoting their tourist business, but in 1900, the railroad laid claim to the land. Morrison took them to court, but the railroad won. In 1908, the railroad turned the land over to the federal government and President Theodore Roosevelt made it a National Monument in May of 1911. It was closed to the public for the next thirty years because congress did not set aside any money to maintain it.

In 1935, Montana Governor Frank Cooney asked the federal government to make the caverns a state park. In 1937, Congress finally signed the papers that made Lewis and Clark Caverns a state park. This was Montana’s first state park. About 200 men from the Civilian Conservation Corp worked to improve Lewis and Clark Caverns between 1935 and 1941. One can still see steps the men carved in the stone floor of the caves. In 1940, electric lighting was installed in the caverns and the park opened to the public in 1941.

Bozeman to Lewis & Clark Caverns (37 miles) - Jump on Interstate 90 and head west until you reach the exit for Highway 287 from there, head south to the Lewis & Clark Caverns.

All the books mentioned are available for purchase at the Gallatin History Museum 317 West Main Bozeman as well as additional photos from the archives.