Riding High: Memories of Yellowstone Travel by Horse

In today’s world, traveling in Yellowstone National Park usually includes plenty of time sitting in traffic jams. For the last one hundred years, cars have dominated park transportation, but prior to 1916, sightseeing depended on the help of equine partners. Those who toured the park before motorized vehicles enjoyed a unique experience and many early employees and tourists remembered the pre-motorized days with fondness. In his 1926 memoirs, early Yellowstone tourism entrepreneur William Wallace Wylie reminisced: “Persons touring the park since 1916, who had visited the park in years previous to that date, are often heard contrasting the pleasure they had riding behind the beautiful matched and well-kept stage horses, with the inanimate motor coaches, in which they ride since the date mentioned. I recall nothing connected with the business while I conducted it with more pleasure and satisfaction than the selecting and buying of horses to match in style and color for four-horse stage teams.”

In pre-road Yellowstone, even before the stagecoach era referred to by Wylie, horses and pack animals allowed early explorers and tourists to cover more ground and see more sites than travel on foot. Trips through the park took weeks or months, but equines made the journey possible. The benefits were great, but it is true that things occasionally went wrong.

In August 1870, the Washburn Expedition departed from Fort Ellis (east of Bozeman) on a journey to explore the area that would later become Yellowstone Park. Among the party was Truman Everts, a 51-year-old former Montana Territorial tax assessor with poor eyesight. On September 8, Everts became separated from the rest of his party while attempting to cross a large area of downed timber. He was confident he would catch up with the group the next morning. Truman Everts spent the night alone and was up early hunting for his comrades. According to Everts’ account of his ordeal, later published in Scribner’s Monthly, the thick forest made it difficult to find the trail. He recounts, “I was obliged frequently to dismount, and examine the ground for the faintest indications. Coming to an opening, from which I could see several vistas, I dismounted for the purpose of selecting one leading in the direction I had chosen, and leaving my horse unhitched, as had always been my custom, walked a few rods into the forest. While surveying the ground my horse took fright, and I turned around in time to see him disappearing at full speed among the trees. That was the last I ever saw of him. It was yet quite dark. My blankets, gun, pistols, fishing tackle, matches—everything, except the clothing on my person, a couple of knives, and a small opera-glass were attached to the saddle.”

Everts wandered in Yellowstone alone on foot for a month, experiencing additional hardships and adventures. By the time he was rescued in early October, he was starving, weak, freezing, and delirious. While Everts’ story had a happy ending, it illustrates the almost complete dependence on horses in early Yellowstone Park.

Thanks in part to fascinating early accounts of Yellowstone from people like Truman Everts, it did not take long for tourists to flock to the area. Bozeman educator and school superintendent William Wallace Wylie authored an early guidebook to Yellowstone National Park in 1882 and stumbled into the Yellowstone tourism businesses soon after. In the early 1880s, there were few roads in the park, and those in existence were subpar. In his 1926 memoirs titled History of Yellowstone Park and the Wylie Way Camping Company, Wylie remembered General Philip Sheridan’s visits to Yellowstone in 1881 and 1882. Sheridan’s visits helped to stimulate road and bridge development in the park, which improved travel for horse-drawn vehicles. According to Wylie, Sheridan’s entourage included “a pack train of 500 government mules, which carried his supplies and luggage and was an interesting show in itself.”

Wylie described the process. “When ready to strike camp, these mules would form in large circles, heads in, and patiently await the removal of their packs, which the packers would place in front of each mule unpacked. When all were unloaded, not one moved until the signal was given to follow the white mare which all pack outfits had for bell animal. She would start for the range and the sound of her bell was the signal for dispersion. If this white mare of the horse tribe lost her bell during the night, the braying of the mules was bedlam let loose. A white animal must be used so that she could be seen in the night. In the morning, when the herd was brought in, all the mules would arrange in the same circles as occupied when packs were being removed, each mule with his nose at the pack which had been taken from his back the evening before…200 of these mules were carrying beer cases. This was before National prohibition, you well know.”

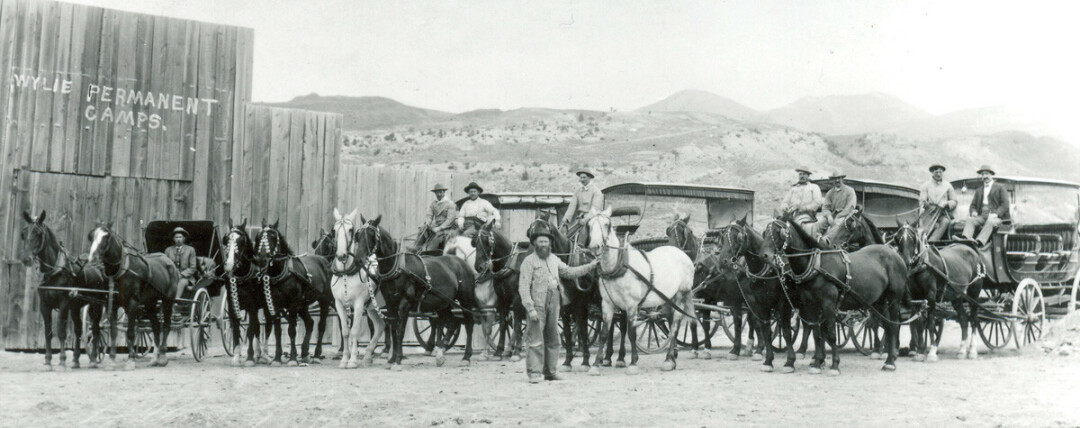

Railroad routes across southwest Montana were well-established by the mid-1880s, and it became easier for people to access the region’s natural wonders. Engineers and work crews built a network of roads and bridges in Yellowstone, making travel by horse-drawn vehicles possible. This in turn led to park tourism on a larger scale. Incorporated in 1896, the Wylie Camping Company offered visitors guided tours of the park by horse-drawn stagecoach. The tours included meals and overnight accommodations in signature striped tents.

In Wylie’s 1926 memoirs, he explained how important horses were to their operation. “One four [horse team] were light colored sorrels with snow white manes and tails. Another four were jet black. Another snow white, another dark bays, another dapple greys, another dapple bays. These teams were really the show teams of the park. It is needless to say that their appearance at the railway station often influenced the undecided arriving tourist in making up his mind as to how he would go. It is needless to give space to telling of the pride and care the drivers of these teams took in their outfits. Their horses and coaches were washed every day, and the driver of the snow white four always used bluing in the rinse water for his.”

Berg Clark worked as transportation manager for the Wylie Permanent Camping Company from approximately 1905 until the automobile’s arrival in 1916. Clark originally hailed from North Carolina and arrived in Montana at the turn of the twentieth century. He worked briefly in Butte before joining a road construction crew in Yellowstone in about 1903. Clark transferred to the Wylie Company a short time later, which was much more to his liking. For most of his career in the park, Berg Clark was responsible for purchasing and caring for a herd of several hundred horses, along with the associated tack, harnesses, and wagons needed for the large camping operation.

According to Clark, a good horse team was worth quite a bit of money during the height of stagecoach travel in Yellowstone. In a 1975 oral history interview, he related that on one occasion he paid $400 for a pair of buckskins from a seller in Bozeman. After automobile travel became dominant in Yellowstone, Clark remembered selling company horses for an average of $35.00 per head—a fraction of their purchased price.

The Wylie Permanent Camping Company used spring wagons to transport visitors between camps. Berg Clark remembered the wagons were shipped in from Racine, Minnesota and assembled at Gardiner. “We had twenty-five come in one time and all tore down, we had to put them together. I had men working in Gardiner putting them together when the train came. The freight train just came in loaded with everything, perfect. You had to put them all together there.”

“Wylie Way” camps were located in popular spots throughout the park, including Swan Lake, Old Faithful, and Grand Canyon. Multi-day sight-seeing tours by stagecoach were economical and all-inclusive. Berg Clark remembered that a five-day coach tour, complete with accommodations and meals, cost $45.00. He recalled that attendance varied somewhat each summer—anywhere from 200 to over 1,000 people. “One summer I hauled 1,500. My horses were just worked to death. I hired 27 teams out of Idaho that came up and worked for me there in the Park.”

Clark witnessed at least one fatal vehicle accident during his tenure in Yellowstone. According to him, the incident began when “A dude bought whiskey and gave it to the driver, and the driver was a man who couldn’t handle whiskey. Scotty was his name, I knew him. Always a wonderful horseman, but when he got whiskey, he just went crazy. And he turned the rig over right below the Golden Gate and killed a man and broke another fellow’s legs.” Clark was called to the scene, but he quickly determined there was no way to help. U.S. Army soldiers took control of the situation and troops removed the injured victim and the deceased man. With nothing else he could do, Clark remembered thinking “Well, those things happen.” He returned to camp and went back to work.

The Yellowstone experience changed again in 1916 with the arrival of automobiles. Iconic yellow tour buses soon shared the roads with family cars and travel became even easier. Perhaps today we are on the cusp of another transportation revolution in Yellowstone Park. A test program was introduced in June 2021 to the Canyon Village area, which includes two electric, driverless shuttle busses. Data collected from this project could provide valuable insight into Yellowstone Park transportation. Could self-driving, electric vehicles mitigate some of the road congestion experienced today and again change how visitors experience Yellowstone?

Maybe one day in the not-too-distant future, we will look back with nostalgia on the days of personal automobile travel in Yellowstone. One day we may experience sentiments similar to those of William Wallace Wylie when he remarked on the first transportation revolution in the Park. “It is doubtful as to whether more real pleasure comes to the passengers in motor bus today than was enjoyed in the concord coach of earlier days. We are not arguing for the return of the stagecoach and horses, it is too late for that. These are gone forever. But they are a pleasant memory for many persons, even younger than the writer.”