Bozeman Women First in Yellowstone

Bozeman women began visiting Yellowstone Park while the ink was still drying on President Grant’s signature on the bill that created it in 1872. By then many of the men who came to Montana for the gold rush had returned to the states to retrieve their families or to find wives. These pioneer women lived near the park entrances and it would be a decade before trains would make Yellowstone accessible to tourists from distant locations. Bozeman women lived closest, so it’s not surprising that they were the first to tour Yellowstone Park.

Doubtless, the first women in the upper Yellowstone were Indians who had lived there for centuries before Euro-Americans explored it. As for white women, there are no official records of their early park visits. Fortunately, Yellowstone travelers have always thought their adventures were worth saving and sharing, so they left a rich record of journals, diaries, reminiscences, and articles in newspapers and magazines. Examination of these documents reveals that white women penetrated the edges of the park by the early 1870s. One traveler described a colony of invalids at Mammoth Hot Springs in 1872. Another tells of a very ill woman brought to Mammoth on a travois to soak in the healing mineral waters. One of the women who visited Mammoth in 1872 was Emma Stone of Bozeman. She is credited with being the first woman to take a complete tour of the park.

Mrs. Stone’s husband, Hiram, caught gold fever in 1849, so he and his brother left their families and joined the California gold rush. After becoming ill in California, Hiram returned to his family and worked as a land examiner for the Illinois Central Railroad. The Stone brothers lapsed in 1862 and again left their families to join a gold rush, this time to Montana. They soon gave up prospecting and began ranching in the Gallatin Valley. Then, in 1868, the Stone brothers returned to Illinois for their wives and children.

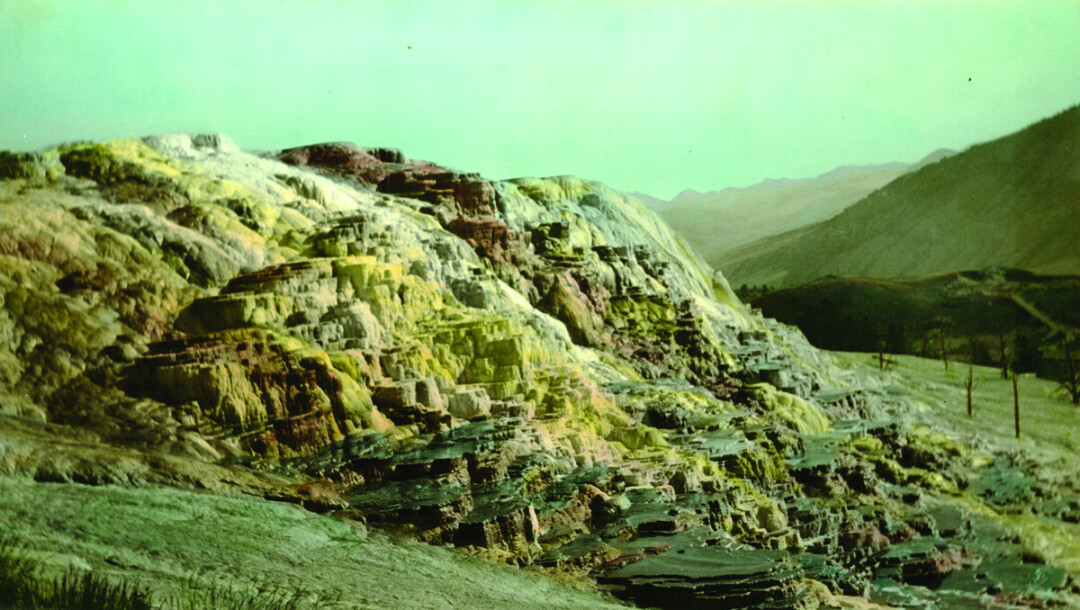

Mrs. Stone’s niece, also named Emma, wrote a reminiscence describing the two Stone families’ trip up the Missouri on the steamship, Twilight. The Stones traveled in steerage with three other families, nine adults and sixteen children crammed into a single room. One day the passengers spied Indians driving buffalo into the river and killing them. The Twilight stopped to avoid hitting carcasses and swimming buffalo. The captain ordered everyone to stay on board because the wounded animals – and Indians – could be dangerous. Where the buffalo tried to get away by climbing the riverbank, “The water was colored red from the wounds of those whose flesh had been torn by the hoofs of the larger and stronger animals as they struggled for safety,” young Emma said. Her Uncle Hiram harpooned a fat young buffalo and the party enjoyed fresh meat for dinner. Colorized photo of Jupiter Terrace at Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park. Photograph courtesy of the Gallatin History Museum.

Colorized photo of Jupiter Terrace at Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park. Photograph courtesy of the Gallatin History Museum.

In 1872, Hiram and Emma Stone and their two sons were visiting Mammoth Hot Springs when two specimen collectors, Dwight Woodruff and E.S. Topping, returned from exploring the park and announced they had discovered a new geyser basin (now called Norris Geyser Basin). Such men often hung around the hotel at Mammoth, looking for people to guide, and the Stones hired them. Because there were no roads, people had to travel on horseback along Indian trails and through timber so tall they could barely see the sky. Horses had to jump fallen logs that covered the ground. Sometimes trees were so close together that pack mules had to get on their knees to squeeze their wide loads under the lower branches. Travelers camped at major sights for days, even weeks. This not only provided an opportunity for such things as seeing many geysers play, but also gave spent horses time to graze and regain strength. Often, the animals wandered off; diaries are filled with accounts of searching for them. The Stones visited all the geyser basins, Yellowstone Lake and Falls. Topping, in his 1888 book Chronicles of the Yellowstone, said, “It was a hard trip for the lady of the party, Mrs. Stone, but she now has the satisfaction of remembering that to her belongs the honor of being the first white woman to see the beauties of the National Park.

Sarah Tracy came to Montana by steamboat in 1869. The day before she arrived in Bozeman, her new husband, businessman W.H. Tracy, told her to dress nicely. As Mrs. Tracy said later, It seems that several bachelors of the town had concluded in the spring that it was not good for men to live alone, and so had started for the states in search of a better half. As this was a long and very expensive journey, the ones who had remained behind were more than anxious to see how the investment would ‘pan out.’ As Mr. Tracy was the first to arrive with his bride, a great deal of interest was displayed.

When she first arrived in Bozeman, Mrs. Tracy was afraid of the Indians camped on the south side of town. She said, “They would peer in the windows if the doors were locked, or come flocking around the door begging for biscuits, soap, clothes, everything.” She recounted this story: One day a big Indian espied a large rain umbrella that I had brought with me from the states, and at once pestered me to trade it for a buffalo robe. He was so persistent that I at last, to get rid of him, made the trade. All day long he paraded up and down the street with the umbrella raised above his head. The next day his squaw had it, but she, becoming tired of it, brought it to the door and flung it on the floor, shouting “heap of dirt, heap of dirt” in great disgust. She wanted me to trade back, but as I would not, she finally snatched the umbrella and stalked off with it. Such encounters left Mrs. Tracy with little fear of Indians.

Indians stole a band of horses the day before Sarah Tracy and her companion, Sarah Graham, left Bozeman for Yellowstone Park in June of 1873. The commander at Fort Ellis didn’t want the party to leave with Indians around, but the stagecoach driver persuaded him to provide an escort. “We were soon on our way with twelve mounted soldiers following us,” Mrs. Tracy said in a reminiscence she wrote about the trip. “With their guns and knapsacks on their shoulders, and their belts filled with cartridges, they looked very warlike.” The soldiers escorted Sarah Tracy’s stage over Trail Creek pass to the Yellowstone River, then turned back after seeing no signs of Indians. The party then headed south to the Bottler brothers’ ranch. Diaries of early trips to Yellowstone often mention a stop at Bottlers.

In 1868, Frederick and Phillip Bottler started the first permanent ranch in the Paradise Valley.9 They chose a propitious spot where springs bubbling out of the mountains joined together to form streams that could be used for irrigation. The Bottlers raised potatoes, vegetables, meat, and milk that found ready markets across the valley, where miners worked gold claims along Emigrant Creek. More important to their lasting fame, the Bottlers’ ranch was a one-day ride from Bozeman, located halfway to Mammoth Hot Springs. That made it an ideal stopping point for travelers heading to the park. The Bottlers always made visitors welcome and eventually started a guesthouse. Besides, Fred Bottler hired out as a Yellowstone guide and was described in several diaries as “a mighty hunter.”

After a night at Bottlers, the stage headed to Mammoth Hot Springs over a new road through Yankee Jim Canyon. This road was so bad that Mrs. Tracy said, “it fairly made one shudder to ride over it in a four-wheeled stage coach.” As the coach approached Mammoth, passengers got a marvelous view from the top of a hill, but the descent down the mountain required chaining the stage’s rear wheels. This “rough locking” slowed the stage by making it skid and keeping it from crowding the horses. “We drove up to the hotel with a grand flourish of the four-horse whip, bringing the landlord and the guests to the door to meet us.” This description conjures pictures of an elegant building, but the “hotel” at Mammoth then was just a 25-by-35 foot log cabin with a sod roof. Crude as it was, the hotel had hot and cold running water; a stream of 40-degree water ran on one side and of 150-degree water on the other.

Mrs. Tracy and her companion, Sarah Graham, waited two days for their husbands to join them. They enjoyed fishing, climbing the terraces, two baths a day and three hearty meals. When the men arrived they all started on horseback for a tour of the Park. “We rode side saddles,” Mrs. Tracy said, “and it was quite difficult for an amateur rider to keep seated.” Their train of a saddle horse for each traveler and eight packhorses made an impressive appearance strung out on the trail. Their route frequently crossed the rushing, boulder-strewn Gardiner River, and Sarah said, I was in great fear of crossing, but as there was no alternative, I had to hold on as best I could. At first, I dismounted to walk over the bad places, but they were so frequent, I concluded to remain in my saddle. One old mountaineer remarked, “Wait until the mountains are so steep you must hold onto the horse’s ears going up, and tail going down.” And we certainly found some mountains where the saddle would slip over the back going up, and nearly over the head coming down. We made only one ride each day, as it was too much work to repack the horses.

At Yellowstone Lake they found the man who had guided Emma Stone’s party, E.S. Topping, and his partner, Frank Williams. The men had recently hand sawed lumber and built a sailboat. The boat makers had announced that the first woman to visit would get the honor of naming the boat. Since Mrs. Tracy and Mrs. Graham both were named Sarah, they decided to christen the boat “The Sallie.” Mrs. Tracy said that after the name was painted on the boat, “We had a fine sail across the lake and our pictures taken on board.” At Topping and Williams’ camp, the men gave the Sarahs “the honor” of making them doughnuts fried in bear grease. In her reminiscence, she said of her twelve-day trip, “The balmy breezes and mountain sunshine had done our complexions to a turn. While our clothing was little worse for wear, yet we had seen the Yellowstone National Park in its primitive beauty. And bear’s grease doughnuts had certainly agreed with us.” Sarah Bessey Tracy and her daughter, Edna Tracy White, pose inside a canvas tent, date unknown. Photograph courtesy of the Gallatin History Museum.

Sarah Bessey Tracy and her daughter, Edna Tracy White, pose inside a canvas tent, date unknown. Photograph courtesy of the Gallatin History Museum.

In 1880, Mary Wylie was a member of the first party to cross the Park from Mammoth to the Lower Geyser Basin in a wheeled conveyance. She came to Montana from Iowa in 1879 with her two children. Her husband, William Wallace Wylie, arrived in Montana the year before to become Bozeman’s first school superintendent. Mr. Wylie came west on the new transcontinental railroad to Corinne, Utah, and then took a stagecoach 800 miles north. When the Wylies took the same trip a year later, they came north on the Utah and Northern almost to the Montana border and by stage from there.

Mr. Wylie left his mark on Yellowstone Park history as a lecturer and interpreter. After his lecture tour, schoolteachers began asking him to guide them into the park. He said this activity “accidentally” launched him into the tourist business. In 1893, he founded the Wylie Permanent Camping Company, which specialized in tours of the park where guests stayed in tents left up for a full season. His moderately priced tours provided competition for the more expensive hotel tours, opening the park to middle class tourists. Wylie first visited the park in the spring of 1880. When he learned that Park Superintendent P.W. Norris was building the first road across the park and planned to have it finished by August, Wylie resolved to bring his wife to the park. He returned to Bozeman, bought a lumber wagon and rigged it with an emigrant cover. He then assembled a nine-person party that included the Wylies and three of their children, a woman friend of Mary Wylie, and three men.

The party met a couple with a spring wagon at Mammoth, who went with them on their tour. This proved to be a good arrangement because the travelers often had to hitch both teams to a single wagon to get up steep hills and through rough country. Superintendent Norris’s new road was extremely rough and sometimes tree stumps were too tall to let the wagons pass. When this happened, the party had to hitch a team to the back of the wagon to pull it back so they could cut the stump lower. This made travel extremely slow so it took more than a week to travel from Mammoth to the Upper Geyser Basin. It was the first time tourists made the trip in wheeled conveyances and Wylie said this fact helped him get licenses to set up his tourist business in the park.

In 1880, the Utah and Northern Railroad track penetrated the southwest border of Montana at Red Rock near Monida. The train ride there left a 100 mile stage ride over rough road to get to Virginia City and then on to the West Entrance to Yellowstone Park, but tourists began using it anyway. In 1883, the Northern Pacific reached Livingston and brought a flood of Yellowstone visitors. Never again were Bozeman women a large percentage of Wonderland tourists.

M. Mark Miller worked as a volunteer at the Gallatin History Museum from 2003 to 2021. His articles have appeared in the Gallatin History Quarterly, Montana Quarterly, Big Sky Journal and Distinctly Montana. He is the author of five books on Yellowstone, including Sidesaddles and Geysers: Women’s Adventures in Old Yellowstone.