A Slight Taste of Disaster: Gallatin County’s 1925 Earthquake

It was a typical summer Saturday evening in Manhattan, Montana. Some families gathered around the dinner table as other folks made their way to the dance at Legion Hall. In Three Forks, the McDonald clan welcomed Belgrade relatives for dinner to celebrate their baby’s baptism, planned for the next day. Moments later, a violent and unexpected event changed the course of the evening for thousands of Montanans. Nobody arrived for the dance, and the McDonald family never finished dinner. Just before 6:30 p.m. on June 27, 1925, a sizable earthquake rattled the windows across Gallatin County.

The quake’s epicenter was north of Manhattan and Three Forks, and caused a shaking that measured 6.75 on the Richter scale. The event remained etched in the minds of Montanans for the rest of their lives, and everyone had a story to tell. Giving up on their meal, the McDonalds scooped up the children and fled as their coal stove bounced off its perch and glided across the room. Fearing for their safety, they spent the rest of the night at a nearby church, where the baby was baptized the next day among the fallen pews.

Retired Milwaukee Railroad engineer E.V. Bennett of Three Forks had a rough time of it when his piano slid across the room and nearly plastered him against the wall. Manhattan resident Violet Lilly was pregnant with her son Bud that summer, and remembers dashing on foot to the barbershop, where her husband was at work. In a 1976 oral history interview, Violet noted that her son “was born the 13th day of August that year and, outran everybody in town. They asked me why he was so fast on foot and I said, ‘well, if you could have seen his mother running before he was born, you’d know why he was fast.’” It was a miracle no one was killed or seriously injured in the quake, although locals were on edge for the next two days as severe aftershocks gripped the county.

People throughout Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming, and even residents of Seattle, felt the tremor. In Butte, hundreds of concerned citizens immediately lit up the local telephone switchboard, wanting to reach loved ones. Other confused residents rang in just to inquire about the commotion. Normally, Butte telephone operators expected about 6,200 calls per hour. That Saturday evening, the switchboard overloaded, with 25,000 calls every sixty minutes. An emergency crew of twenty-eight operators worked so feverishly that seven of them fainted. Luckily, each operator recovered quickly and returned to work.

Most of the damage was confined to southwest Montana, particularly Manhattan, Three Forks, and Logan. Inside local homes, dishes crashed to the floor, pictures fell, and furniture suddenly became mobile. House exteriors fared slightly better, though chimneys suffered the most. Virtually every brick chimney in Manhattan and Three Forks was either toppled or twisted beyond use. The same Mr. Bennett who was almost flattened by his piano emerged a celebrity, as he owned an electric range. He later recalled that fifteen chimney-less families, fearful of house fires, made use of his range for cooking meals while their hearths and wood stoves awaited repair.

Brick and stone public buildings fared much worse than the smaller, more flexible frame houses. Manhattan native Francis Niven arrived in town with the Hays family just after 7:00 pm for a dance, only to find the streets deserted. Looking back, he marveled that nobody had died from the fallen bricks and cornices that littered the crushed sidewalks. In Three Forks, two banks, the Avery Garage, and the Methodist Church exhibited severe devastation. The Manhattan State Bank and the Kid Theater were among the hardest hit in Manhattan.

Bozeman buildings survived the shaking much better than their counterparts in western Gallatin County, although there was some minor damage. In the days following the disaster, the Bozeman Weekly Chronicle reported fallen chimneys and cracks in walls. Several distinctive towers and architectural features on downtown Bozeman buildings were removed after the 1925 earthquake. According to the Chronicle, cracks formed in the Commercial National Bank building (US Bank today), on the southeast corner of Main and Black, and the bell tower on the old Irving School (located where the Emerson lawn is today) had to be dismantled.

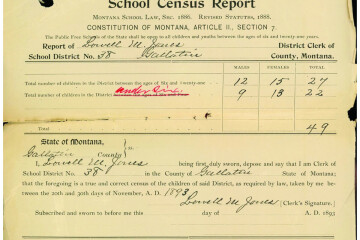

Unfortunately, county schools sustained the most damage. Three Forks Consolidated School, Manhattan Community High School, and Manhattan Grade School all crumpled at their tops. Brick schools in Willow Creek and Logan were also deemed unsafe for children. Repairing these educational facilities proved to be a major problem. The school systems affected by the quake had already reached their legal limit of bonding, and the law denied a reinstatement of taxes to raise the $62,000 required to repair five area schools. A county delegation made up of Manhattan, Three Forks, Logan, and Willow Creek school superintendents and board members traveled to Helena, requesting state help. Concerned citizens feared for the future of education in these communities, as expressed by Miss Lucile Quaw, County Superintendent of Schools, in the July 9th edition of the Bozeman Weekly Chronicle: “It is not a question of the children being deprived of schooling for one year, but for many years to come.”

In July, Montana Governor John Erickson established committees across the state which were responsible for gathering monetary donations for Gallatin County schools. Officials believed that most Montanans would jump at the chance to help their fellow citizens in need. Their attempts failed miserably. The committees raised only a fraction of the money by August, and things looked grim for the start of school in the fall. Salvation eventually came, but in a rather unconventional way.

Manhattan resident Harry Altenbrand promoted a series of boxing matches to raise funds, which suggested that people were more apt to part with their money if they could view a bloody bout in return. The well-organized fights drew local favorites in addition to men from Roundup and Ennis. Popular Manhattan animal trainer, businessman, and former pugilist Kid Johnstone trained several competitors. Even a young Hubert “Kid” Dennis, who later ranked fourth in the world in the light-weight division, put on a good show. Thanks to local boxing enthusiasts, Manhattan Schools were open for business by mid-September.

The 1925 earthquake also destroyed the Milwaukee Railroad’s path through Sixteen Mile Canyon at the northern end of the Bridger Mountains. Rockslides dammed the flow of water and created a lake sixty feet deep. One fascinating incident involved a passenger train, which traveled through the canyon in two sections that evening. One section passed through Tunnel #8 just moments before the quake hit, closing the tunnel. The train eventually limped into Lombard without power. Work began almost immediately to clear the canyon of debris and fix the damaged track. Within forty-eight hours, several hundred men and thousands of pounds of dynamite arrived. The crew worked around the clock and had the area clear for rail traffic by July 10, 1925.

That summer Saturday night likely passed slowly for most residents, as aftershocks came in waves every couple of hours. Most spent the night outdoors. Terrified of flooding, some Three Forks residents moved to high ground, anticipating a break in the Madison Dam nearly forty miles upstream. Witnesses even reported that the water level of the Jefferson River dropped several feet. Great cracks in the earth magically appeared, and creeks and springs used for irrigation suddenly dried up.

Despite the hardships, locals realized it could have been much worse. As an editorial in the Bozeman Weekly Chronicle stated on July 2, Gallatin County had been lucky. “The slight taste this community received of earth shocks gives some idea of what the peoples in the countries where they are comparatively frequent have to undergo. Sympathy with these people will be more acute after our own experiences.”