The Montana Gin Marriage Law In Gallatin County

The Gallatin County Clerk didn’t issue a single wedding license in July and August of 1935—and that wasn’t normal. In fact, there were 46 licenses issued in those months in 1934, and 52 in 1935. The reason was Montana’s new “gin marriage law,” which required a physical exam and a three-day waiting period before a wedding license could be issued. That law, which went into effect on July 1, 1935 was supposed to keep people from rushing into marriage. In fact, the name “gin marriage” was coined during prohibition to describe the unions of couples who got drunk on bathtub gin on Saturday night and woke up Sunday morning to discover they’d gotten married.

States across America passed such laws in the 1920s and 30s. Most of them just required a short waiting period, and maybe a blood test for venereal disease, but Montana’s law was different. It said couples had to get a physical exam and a certificate from a doctor saying neither of them had any of a long list of diseases, and—more important—that they wouldn’t have a defective child.

The Montana law had teeth. Doctors who signed the certificates without giving a proper physical would be guilty of a felony and could lose their licenses to practice medicine. Doctors said signing the certificates would make them liable for damages if either member of the couple came down with any of the listed diseases or had a defective child. Doctors said they couldn’t certify such things and refused to issue the certificates. Without the certificates, county clerks couldn’t issue marriage licenses. Couples didn’t know they wouldn’t be able to get marriage licenses in July, but there was a rush to buy them in June anyway. Apparently, they were trying to save money. The physical exams could cost up to $25 a person—far more than couples wanted to pay during the Depression.

Sixty-five couples bought marriage licenses in Gallatin County in June of 1935, compared to 18 in 1934, and 32 in 1936. The frenzy to beat the July 1st deadline, when the new law would take effect, peaked in the last week of June when 30 Gallatin County couples purchased marriage licenses.

Some of these couples might have gotten married regardless of the new law, but many of them probably rushed to the altar to beat the costs, or the new Montana law. Gin marriage laws were popular in the 1920s and 30s because of rising divorce rates and several well-publicized cases of people requesting annulments on the grounds that they were drunk when they got married. But the Montana law wasn’t just a late entry into a national movement. It was a eugenics law.

The British scientist Francis Galton, who coined the term “eugenics” late in the nineteenth century, believed that genes control not only physical characteristics like hair and eye color, but also behaviors like feeble-mindedness, pauperism and criminality. Because of that, Galton said, society could be improved by applying scientific principles to human breeding.

In the United States, psychologist Henry H. Goddard popularized the notion that feeble-mindedness is inherited in his 1912 book, The Kallikak Family. The book purported to trace the descendants of Martin Kallikak, a revolutionary war soldier, ‘M.’ One side of Martin’s family descended from his illicit liaison with a “feeble-minded” barmaid, another from his marriage. The barmaid side of the family, Goddard said, contained generations of poor, criminal, insane and retarded people, while descendants of Martin’s wife were doctors, lawyers, and ministers. From this, Goddard concluded that mental defects are hereditary, so society should prevent people with them from having children.

Eugenics enjoyed substantial support from clergy, doctors, educators and public officials at the dawn of the twentieth century. By the 1920s, eugenics advocates had successfully promoted policies such as forced sterilization of “the mentally defective” in several European countries and 18 U.S. states, including Montana. In 1923, the Montana legislature approved forced sterilization of the “feeble-minded” by an overwhelming legislative majority. Sterilizations began immediately at state facilities, and the law wasn’t repealed until 1965.

Montana embraced eugenics in many ways. The State Fair Committee, State Board of Education and State Board of Health all promoted the idea. Through these agencies, the state held “better baby contests” at county fairs, taught eugenics in schools and colleges, and distributed pamphlets admonishing people to be careful about their sex partners. The United Press wire service reported that only five marriage licenses were issued in the entire state of Montana during the two months the gin marriage law was in effect.

On July 10, the Great Falls Tribune published an article stating that attorneys had found a 40-year-old law that provided for “contract marriage.” All a couple had to do to get married under the old law, the attorneys said, was draw up a marriage contract and file it with the county court clerk. Other attorneys doubted the legality of contract marriage because the gin marriage law stated: “All acts and parts of acts in conflict herewith are repealed.” Another hitch was that the old laws said contract marriages could not be sanctified by anyone licensed to perform marriages. Many clergy said they opposed contract marriages because unsanctified unions were sinful. Nonetheless, couples started filing marriage contracts in Great Falls on July 13, and in Missoula on July 17, and the practice spread. United Press reported that some 30 marriage contracts were filed during the period the gin marriage law was in effect.

A Belgrade couple decided to take advantage of the marriage contract law. As the Bozeman Chronicle put it, “Dan Cupid was not put out of business in Gallatin County when the new ‘gin’ marriage law went into effect July 1, although the marriage license business stopped.” The Chronicle reported in its August 9, 1935, issue that Roscoe Holcomb and Geraldine Bates researched the situation and concluded that contract marriage was just as binding as any, so they got a Belgrade notary public, W. O. Gedoch, to draw up a contract, which they signed and took to Bozeman to file with clerk of the district court. Then they returned to Belgrade to make their home.

The Holcomb-Bates contract marriage made the front page of the Chronicle, but the newspaper apparently missed another Gallatin County contract marriage. On July 15, Bruno Collins and May Cora Grover filed their contract with the District Court Clerk. Cut? Kind of boring.

Newspaper stories before the law took effect described the founding of a state facility to process required blood tests, and speculated that couples might flee to nearby states. On July 19, William A. Patt, a retired judge in Dubois, Idaho, announced plans to establish a “Gretna Green” so Montanans could get married without waiting. Common at the time, the term Gretna Green came from a village just inside Scotland, where the English had fled since the seventeenth century to escape restrictive marriage laws.

When a gin marriage law took effect in California in 1927, several Nevada towns became Gretna Greens. In Reno, three-quarters of the marriage licenses issued went to Californians the year after that state began requiring a three-day waiting period. At the same time, the number of marriage licenses issued in California fell by nearly a quarter. A similar pattern occurred in Oklahoma border towns in 1929, when a gin marriage law took effect in Texas.

To justify establishing his marriage mill in Idaho, Judge Patt said; “It isn’t right, that system in Montana—that discourages marriage.” He offered to perform marriages “at any hour of the day or night.” An Idaho marriage license cost three dollars, and Judge Patt charged five dollars to perform the ceremony, a tidy profit for the kindly old judge.

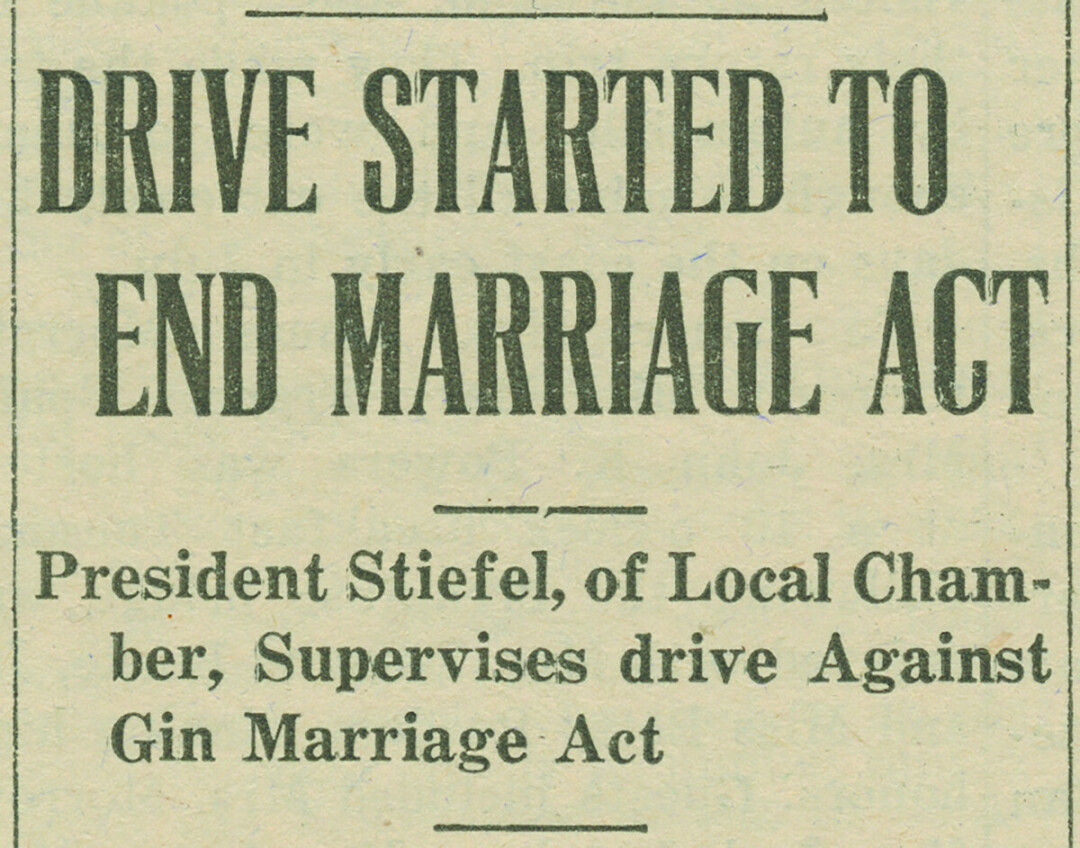

By the end of July, a citizen’s group in Billings announced plans for a petition to put the gin marriage law on the 1936 election ballot. Billings Federation of Women’s Clubs immediately joined the referendum effort, spearheaded by the Billings Commercial Club. The organizers sought help from chambers of commerce, commercial clubs, and women’s club federations across the state.

An article in the Bozeman Chronicle of August 9th that year reported that the Chamber planned to circulate petitions in Gallatin, Madison and Meagher Counties. The Chronicle explained that the controversial law would be suspended as soon as the secretary of state certified that as at least five percent of the voters from at least 40 percent of the counties signed the petition. The signatures had to be collected within six months of the end of the session when the law was passed. That left just over a month to gather signatures, have county clerks verify them, and submit them to the secretary of state. Hundreds of volunteers began canvassing door to door to beat the deadline.

By September 4th, 41 counties turned in petitions with 21,648 signatures, more than the required number. The September 6th issue of the Bozeman Chronicle announced the end of the law under a front-page headline that read, “Gin Marriage Law Suspended by Montana Voters Petitions.”

The next day, Montanans began buying wedding licenses and getting married. John Dykstra and Priscilla (Pearl) Dyn bought the first marriage license issued in Gallatin County in more than two months on September 9th.

With couples getting married without hassles, the gin marriage law quickly faded from memory. When it appeared on the Montana election ballot in 1936, sixty-four percent of the voters rejected it.

Nine months after couples rushed to the altar to get married before the gin marriage law took effect, many of them rushed to the delivery room to welcome a new addition to the family. People who were born to Montana newlyweds in March of 1936 might think of themselves as “gin marriage babies.”

M. Mark Miller worked as a volunteer at the Gallatin History Museum in Bozeman from 2003 to 2021. His articles have appeared in the Gallatin History Quarterly, Montana Quarterly, Big Sky Journal and Distinctly Montana. He is the author of six books on Yellowstone stories and history.