The Wood Wide Web

I grew up surrounded by trees. The Knight family home in Connecticut was tucked into a forest of oaks, white pine, maple beech and hickory. Our small yard was home to hundreds of trees, mostly black oak. The forest was filled with birds, squirrels, raccoons, snakes, salamanders, toads, and insects. Cicadas buzzed on hot summer days and whippoorwills hooted all night. As a child, I ran wild in the woods with my friends, building forts, playing hide and seek, hiking steep hills, mucking about in swamps, climbing and falling out of trees. In Boy Scouts I continued to explore New England’s big woods with my friends. While the woods of New England have long since been logged over, all the big pines cut down, and all the huge chestnuts gone, it is still big woods.

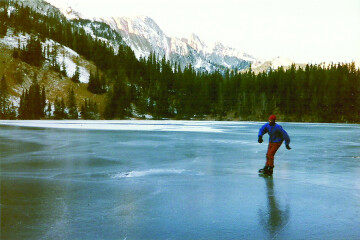

I’ve spent a lot of time in forests, exploring, learning, camping, hiking and defending. As an environmentalist, my interest in preserving intact forests has taken me around the world, to places I would otherwise never have seen. I’ve traveled from the Araucaria forests of Chile, to the boreal forests of Siberia and arctic Sweden, to the hardwood forests of the Russian Far East, to the southern beech forests of New Zealand, to the eucalypt forests of Tasmania and the rainforests of mainland Australia, to the mind-blowing redwood forests of California and the temperate rainforests of Alaska.

Forests and trees provide us with so many amazing things: Shade, color, beauty, homes for wildlife, wood to burn and to build with, nuts, fruit, and peace and quiet. They hold the soil, moderate the weather, soak up carbon, exhale oxygen, and transpire water. Forests provide homes for a vast array of terrestrial wildlife.

Trees can live for thousands of years and spread across hundreds of acres. A bristlecone pine in California is over 5,000 years old. An Alerce in Chile may be older than that, and a spruce in Sweden may be as old as 9,000 years. An aspen clone in Utah, spread over 106 acres, is the largest single organism ever found.

Humans evolved in the forest and began walking upright when we descended from the trees. We feel at home in the woods. It’s no wonder forest bathing is beneficial to humans — it takes us back to our true home. Called Shinrin-yoku in Japan, where it has long been practiced, forest bathing has been shown to help regulate human blood pressure, benefit the digestive system, enhance the number of defensive cells in the human body, and reduce stress, anxiety, depression and other mental health problems. And it costs next to nothing.

There is so much going on in the woods, much of it unseen. A New York Times Magazine article titled The Social Life of Forests describes how dynamic and interactive forests really are. Author Ferris Jabr wrote; “An old-growth forest is neither an assemblage of stoic organisms tolerating one another’s presence nor a merciless battle royale. It’s a vast, ancient and intricate society.” He goes on to say; “The trees, understory plants, fungi and microbes in a forest are so thoroughly connected, communicative and codependent that some scientists have described them as superorganisms.”

Fungal strands permeate all forest soils and form a network connecting trees and plants—even different species. This network has come to be called the Wood Wide Web. Trees share resources and information through this web and support one another rather than constantly competing. Mother trees help their offspring to survive. Trees warn each other of impending danger. They communicate on many levels.

Jim Robbins wrote in the New York Times, “We have underestimated the importance of trees. They are not merely pleasant sources of shade, but a potentially major answer to some of our most pressing environmental problems. We take them for granted, but they are a near miracle.”

Most terrestrial wildlife depend on forests. Every time scientists venture into the canopy of an old growth forest, they discover more species. Everything from voles to lemurs, owls to orangutans, depends on forests. We do too. The trees on the mountains surrounding the Gallatin Valley are not just a scenic backdrop or a source of cheap Christmas trees—they are essential to our very survival.

Just because trees cannot travel it does not mean they are not on epic journeys. Forests have been around for tens of millions of years. They travel through the cosmos on planet Earth just as we do, circling the sun and wheeling through the Milky Way.

Forests are also under great pressure from humans. With over 8 billion of us, all natural spaces and systems are in peril. We are losing an estimated 23 million acres of forest worldwide every year. One third of Earth’s forests are gone. We need to be planting trees and protecting old trees, not cutting them down. I’ve spent dozens of hours in the last few weeks writing comments on the US Forest Service’s plans for massive logging projects in Montana. Given that the Forest Service is eager to cut down millions of publicly owned trees, I sure do have job security.

There is hope. New England has gained forest cover in recent decades. Deforested countries like Scotland are planning rewilding and reforestation projects. As the forests return, so does the wildlife. Forests are complex and fascinating systems, with much to teach us about cooperation, evolution, ecology, diversity, longevity and survival. We have hardly scratched the surface of the endless knowledge and inspiration that trees and forests have to offer. John Muir called big trees “Nature’s forest masterpiece,” the greatest of all living things.

Next chance you get, go sit under a tree. Walk through the forest. Think about all that is going on there, seen and unseen. This great green world keeps growing, evolving, expanding, interacting, and existing, as we go about our busy lives, often taking it for granted.