Yellowstone Park Boundaries

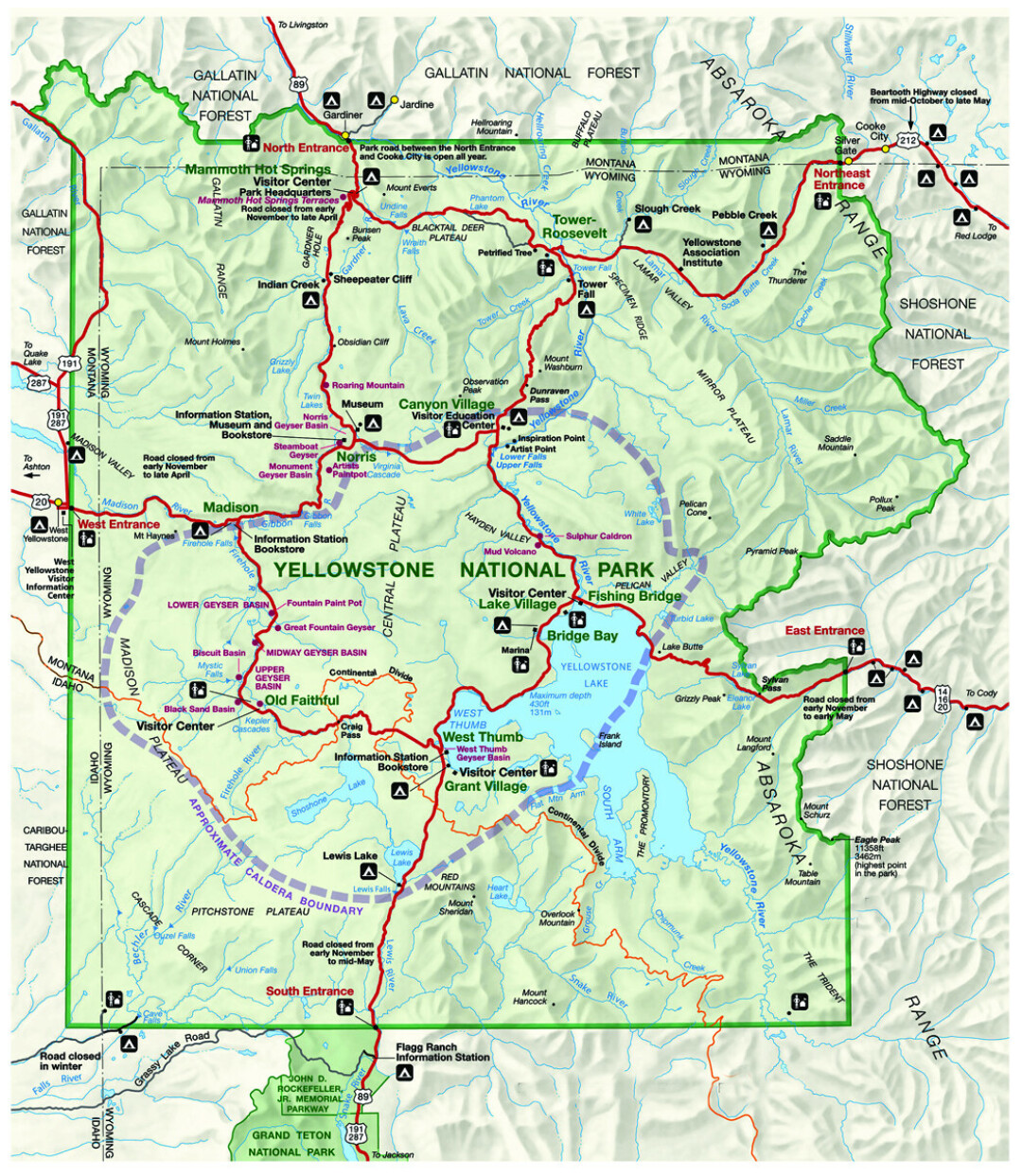

Yellowstone Park forms a rectangle of land in northwest Wyoming. Mostly. The Congressional Act that set aside Yellowstone as a National park listed the boundaries in miles from certain landmarks, then stipulated the meridians thus encountered. The western boundary is listed as a north / south line fifteen miles west of Madison Lake, a small lake on the Firehole River to the west of Shoshone Lake. The eastern boundary is a line ten miles east of the easternmost point of Yellowstone Lake. The northern boundary was designated as the confluence of the Yellowstone and Gardner Rivers. The southern border is a line ten miles south of the southernmost point of Yellowstone Lake.

These border descriptions are local, extending outwards from specific points. Originally proposed by the Hayden Survey of the area in 1871, they are not oriented to the base point of the Washington, D.C. Meridian that was used to determine the territorial borders, later the state borders, of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. Thus the rectangle of Yellowstone, though chiefly located in Wyoming, overlapped into Idaho and Montana.

Over 150 years later, the western and southern borders remain the same. The northern and eastern borders have been altered. At various times there have been proposals to change all of the borders, indeed, to change the nature of the Park.

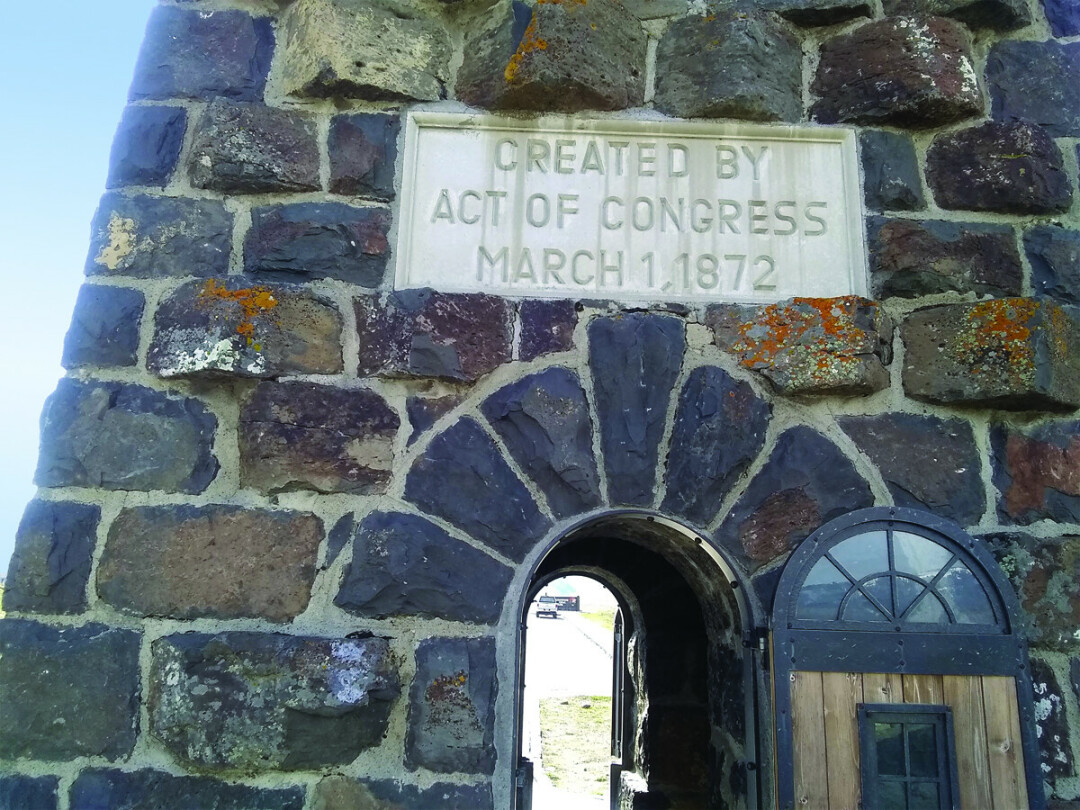

Congress, after declaring the Park in 1872, did not appear to want or know how to deal with it. Funds were sparse, sometimes not allocated. The concept of a park, let alone a national park, was new. Superintendents, working for the Secretary of the Interior thousands of miles away, were subject to local pressures. Visitors also did not understand the park concepts and caused injury to natural features and wildlife, and carelessly tried to burn the place down.

Interestingly, rather than employees, two prominent visitors had the greatest effect on Yellowstone in its early years. The first of these was Philip Sheridan, the commanding general of the U.S. Army. He toured the Park in 1882 when some politicians in D.C. were already saying that the place was too big. General Sheridan advocated making it much bigger. He proposed extending the borders ten miles to the south and forty miles to the east, mostly as an effort to provide more habitat for wildlife. All of this area remained virgin wilderness. In fact, the only towns near Yellowstone at the time were Bozeman and Virginia City. All ventures into the Park originated at one or the other of these locations.

Sheridan’s recommendation was proposed to Congress but did not pass. At that time, the borders remained the same. But later, this idea had far-reaching consequences for the country. General Sheridan’s other contribution to Yellowstone probably saved the Park. In 1886 he sent a company of cavalry to take over from the ineffectual civilian leadership. The Army remained in Yellowstone for thirty years.

Yellowstone became a popular destination early in its history. The conditions were primitive, the journey long and difficult, yet many people made the trip. The most famous was probably President Teddy Roosevelt. He passed back and forth through the Park on a Wyoming hunting expedition in 1891, but his official trip while President in 1903 was much publicized. He dedicated the arch at the North Entrance at Gardiner, which bears his name. He camped at Tower Fall near the location at the intersection of the Cooke City road that is also named for him. Roosevelt made suggestions toward wildlife policies that were ahead of the times. If they had been adopted, many years of conflict may have been eased. By all accounts, Teddy had a rousing great time. Roosevelt had founded the Boone and Crockett club in 1887, which began as an organization dedicated to hunting and game preservation. Yellowstone was a primary focus. Wildlife issues meant habitat issues, which meant forest conservation. Teddy Roosevelt was involved all his life with what became the National Parks and National Forests.

The country was founded on the Jeffersonian concept of the smallholding yeoman farmer. This worked well for decades up to and even beyond the Mississippi River. However, in the west, with its vast mountains, deserts, and forests, that system did not work. The idea of the federal government owning large tracts of land was not popular, nor at first considered. The setting aside of Yosemite as a state reserve and Yellowstone as a national reserve were the first actions in that direction. The land additions suggested by General Sheridan were eventually adopted, but as the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, not as part of the Park. Later, this area became the basis for the creation of the U.S. Forest Service during Roosevelt’s presidency.

The railroads saw the potential of the National Park even before it was proclaimed. Profit potential. The Northern Pacific Railroad built track across North Dakota and Montana partly to access Yellowstone. It made proposals to either be allowed to build lines into the Park or that the Montana strip be removed from Yellowstone, enabling them to claim the land and build track to the edge of the Park, as well as to access the mines near Cooke City. This bit of piracy never occurred, though it was a near thing during various sessions of Congress in the 1880’s and 1890’s.

Later the Idaho strip was threatened by interests from that state who desired an irrigation project within the Park. The Belcher River area in the southwest corner of the Park is virgin wilderness. Very few visitors ever go there. There are a couple of short in and out roads. The Idaho interests wished to dam some small lakes within Yellowstone to benefit farmers with enhanced irrigation. The ‘no one ever goes there; it is just a swamp’ argument was employed. This failed, yet advocates of these and other projects spent many years in their efforts. One of their techniques was to reason that if their projects could not be accomplished within the National Park, then the land should be withdrawn from the park and given to them. So far, this has not been successful.

The odd areas of the Montana and Idaho strips have also inspired politicians. At various times both states have lobbied to be given their land back. Failing that, they have desired governmental control of that land, or even the entire Park. This has not happened. Yet, economically, West Yellowstone, Gardiner, and Cooke City reap the rewards of their proximity to Yellowstone.

So, there have been land grab attempts by farming, mining, logging, and railroad interests, as well as political schemes. There have been grandiose visions to add on to Yellowstone, including Sheridan’s and another that would have extended the Park to the south of the Tetons. But the one proposal that was successful and fairly modest was, for the most part, common sense. Still, it took decades and dozens of battles on the ground and in Washington D.C.

Around the time of the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, a movement became public that advocated a concept called the Greater Yellowstone. A refinement of General Sheridan’s old proposal of enlarging the Park, it considered preservation of habitat and wildlife migration, along with natural boundaries rather than the straight lines on the map. A bill was introduced into Congress in 1918 that would have extended Yellowstone south to Jackson, Wyoming, including the Teton range and much of Jackson Hole. This would have increased the 3400 square miles of the Park by over 1200 square miles. It came very close to passing.

Before the bill could be re-introduced in the next session, some small special interests objected. All the land involved was federal, yet the proposed Park extension was in National Forest areas. Ranchers and hunters did business there, grazing and taking game in the forest. They would not be able to do that in a National Park. So, a very few people with political connections stopped this legislation.

Throughout the 1920s, various compromises and schemes were considered. It seemed there were always some small special interests who were unhappy with any plan. Finally, in 1929, a plan was approved to alter the plain rectangle boundaries on the north and east by drawing the lines on ground features of stream drainage and mountain crests. The total area of gain and loss to the Park was negligible. Neither the Yellowstone River headwaters, called the Thorofare, nor the southern extension into Jackson Hole were included. The ranchers and hunting guides won that one.

Grand Teton National Park, while not allowed as a Yellowstone extension, was created the same year in separate legislation. The Yellowstone borders were extended in 1932, when Burton K Wheeler, a senator from Montana, attached a donation of land at the northwest corner of Yellowstone to a highway bill. This 7600 acre tract completed the boundary revisions. They have remained the same into the 21st century.

It is worth noting that the Yellowstone Boundary Commission which recommended the 1929 topographical corrections did their research on horseback within the Park rather than gazing at maps in an office. They performed their survey on the ground and came up with boundaries that reflected the natural contours of the land and the streams.