Cooper Park part 1

The Cooper Park Historic District is a tangible reminder of Bozeman’s amazing transformation between 1883 and 1945. Residential construction in the district spans three phases of the community’s history and the homes showcase almost every architectural style popular during the 50 year period. The variety residences in the Cooper Park District made the area Bozeman’s most economically and socially diverse neighborhood during the early 20th century.

As Part I of the Cooper Park Historic District spotlight, this article covers the area’s development between 1883 and 1929. Part II, which will be published in the November Bozeman Magazine, will describe residential construction in the neighborhood during the economically turbulent years between 1930 and 1945.

Arrival of the first Northern Pacific Railway train in March 1883 heralded the onset of Bozeman’s Civic Phase of development. During this time period, the community harnessed the resources of an incorporated City of Bozeman local government to fund civic improvements. Voters approved bonds to purchase the water system and levied Special Improvement District taxes to build and expand the street network and other public works projects.

At the same time, real estate investors anticipated that the Gallatin Valley’s agricultural productivity and proximity to the transcontinental railroad would create growth and prosperity. To capitalize, investors began annexing large portions of property to the Original Town Plat.

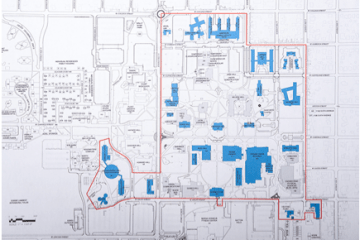

Most of the properties in the Cooper Park Historic District lie within the Park Addition, which added 52 city blocks to the south and west of the City of Bozeman in May of 1883. This plat established a regular street grid in an area 11 blocks east to west (between S. Tracy Avenue and S. 11th Avenue) and six blocks north to south (between W. Olive Street and W. College Street), and set the tone for most of Bozeman’s south side residential expansion.

As an amenity to the residential area, the investors set aside two blocks at the heart of the Park Addition as a public park. The park is now named for Walter Cooper, a major Park Addition investor. An entrepreneur who arrived in Bozeman in 1869, Cooper was represented by Peter Koch in the Park Addition proceedings, likely due to Cooper’s position as a member of Bozeman’s first City Council and President of the Bozeman Board of Trade. Other Park Addition investors included Nelson Story and John Dickerson.

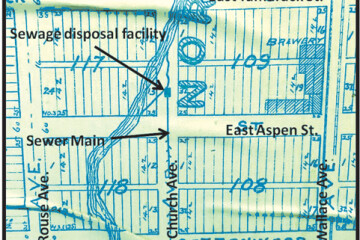

Setting a pattern repeated throughout the Cooper Park District’s development, installation of a water main preceded the first residential construction in the area. In 1885, builders constructed Queen Anne style residences along either side of the 400 block of West Olive Street, where a new six inch iron main delivered water service.

The Queen Anne style dominated domestic building construction between 1880 and 1900. Queen Anne residences are characterized by their steeply pitched roofs of irregular shape, dominant front-facing gable, patterned shingles, bay windows and asymmetrical façade with a partial or full width porch.

Queen Anne is actually a subset of the “Victorian” architectural styles; named for Great Britain’s Queen Victoria and which were popular in the USA between 1860 and 1900. Pattern books made house plans accessible to the growing middle class. According to architectural historian Virginia Savage McAlester, “…growing industrialization permitted many complex house components- doors, windows, roofing, siding, and decorative detailing- to be mass-produced in large factories and shipped throughout the country at relatively low cost on the expanding railway network.” Other Victorian subsets include Second Empire, Stick, Shingle, Richardsonian Romanesque and Folk Victorian styles.

The residence at 412 West Olive Street is an example of the mail order phenomenon. It was built from specifications in Fred Hodgson’s mail order pattern catalogue, and is an excellent example of Queen Anne Style.

Montana Territory’s statehood in 1889 directly impacted the Cooper Park neighborhood. As part of the statehood process, the legislature asked voters decide the final location of the state capital in an 1892 vote. Bozeman’s boosters immediately began civic improvements to make the community more impressive to voters. The Northern Pacific Railway replaced the original frame passenger station with an impressive brick structure (later remodeled in 1924). The City constructed a three story City Hall and Opera House across Main Street from the new Hotel Bozeman. Electric street lighting was installed, followed shortly by electric streetcar service.

To both impress voters with the community’s perceived size, and potentially capitalize on the building boom sure to follow the statehouse to Bozeman, real estate developers annexed huge tracts of land to the City plat between 1889 and 1892. Ten additions south of Main Street, including two located so far east of what is now Peete’s Hill that they were platted as “suburbs to the City of Bozeman,” added over 250 blocks to the City’s plat. By the summer of 1892 the street grid reached from what is now Bozeman Trail Road to South 15th Avenue.

Boosters intended to locate the state capitol buildings on a rise to the south and west of Cooper Park. Accepted in August 1890, the ambitiously named “Capitol Hill Addition” added 52 blocks to the city plat and covered the hill south of Cooper Park. The addition was backed by Minneapolis investor Louis Menage, whose Guaranty Loan Company financed real estate investments across the northern tier states before collapsing in the financial panic of 1893.

To create a more grand entrance to the proposed site of the state capitol buildings, Menage acquired ownership of the Park Addition west of South 8th Avenue and re-platted the property. The 1892 West Park Addition plat removed 40 feet from the blocks between South 8th and 9th, which expanded the South 8th Avenue street right of way from 60 feet to 100 feet, creating a grand entrance boulevard to the rise of the hill.

Bozeman came in fourth in the state capital campaign. As a runner-up prize, the legislature located the state’s Land Grant Agricultural College at the heart of the Capitol Hill Addition. Walter Cooper, who participated in the state’s Constitutional Convention, was appointed by the governor to the executive board of the newly-established Montana State College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts, alongside Peter Koch.

Residential construction in the Park and West Park Additions continued to follow the installation of water lines. By 1904 residences were clustered along the water lines on South 5th, South 6th, South 7th and South 8th Avenues, where a main carried water to College Hill.

The residences along South 6th Avenue represent the spectrum of architectural styles built in the district after 1900. It was also where a handful of building contractors purchased lots and built speculative homes, often in groups, which were sold once complete.

Builder Andrew J. Svorkmoe constructed two investment homes in the Colonial Revival style at 221 and 224 South 6th Avenue in 1906-1908. The residence at 221 South 6th Avenue is an example of the Dutch Colonial Revival style, which created second floor living space under the steeply pitched gambrel roof. Both homes are balloon frame construction with a brick veneer. Svorkmoe used this new technique for adding a masonry exterior to a frame structure on most of the nearly 60 residences he built before his death in 1924.

Water lines crisscrossed the neighborhood by 1912, setting the scene for a residential construction boom. The 1910’s and 1920’s are associated with Bozeman’s Progressive Phase of development, so named for the legislative attempts to address social ills during the era. Women’s suffrage and prohibition were implemented alongside evolving economic theories which emphasized industry, economy and mechanization. Automobiles also became widely available in this era, and garages began to show up in the Cooper Park neighborhood.

The Craftsman Bungalow residential style epitomized the Progressive Era. The style incorporated a front porch, low-pitched roof lines and an interior division of public and private spaces, was viewed as a scientific, practical, modest home that could reform both rich and the poor to create a norm for those in between. As with previous development in the Cooper Park neighborhood, innumerable pattern books and catalogues featured everything from plans to precut components for assembly.

W.H. Cline built a series of Bungalows on the 300 block of South 6th Avenue in 1914. Between 314 and 316 South 6th, Cline included a shared driveway which gave vehicular access from the street to garages located at the rear of the property. Builders like Ora Long, E.L. Bartholomew and Guy Ensinger proliferated the Bungalow style in the Cooper Park neighborhood; over 40% of the houses in the Cooper Park Historic District are Bungalows.

By the 1920’s the Cooper Park neighborhood was home to a variety of community members. Census records indicate that about half of the residences were owner-occupied. Owners in the neighborhood included store clerks, the registrar at MSC, bank presidents and professors. Professors and students, appreciative of the neighborhood’s proximity to the MSC campus, rented houses in the area. Other tenants included ranchers, who moved in to town over the winter months in order to send their children to school at Gallatin County High School.

The Cooper Park Historic District’s continued evolution during the 1930’s will be discussed in Part II of this article.