Hunter's Hot Springs

The Forgotten Opulence of a Bygone Era

Long before any emigrants came to the Northwest, Native Americans would carry their sick to the place that would later become known as Hunter’s Hot Springs, 20 miles east of Livingston, to bathe in and drink the hot and healing waters. The hot springs were in Crow country, and at certain periods of the year, hundreds of members of that tribe would camp there.

Andrew Jackson Hunter was born in Virginia in 1816 and became a physician at a rather early age in Louisiana. By 1856, Dr. Hunter was serving as a physician for the Illinois Central Railway. After the death of his first wife, he moved to Benton County, Missouri, where he married his second wife Susannah.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Dr. Andrew Hunter entered the Confederate Army as a surgeon. Dr. Hunter’s family had been slave holders and possessed considerable wealth, which had not been dissipated by the war. Relocating to Missouri as the war was coming to an end, the couple and their small family acquired a substantial farm, a general store and drug store, and a spacious home. The closing days of the war, though, brought an end to their lives there--seen as Southern sympathizers and with his participation in the Confederate army, their home and store were burned to the ground. So began their trek west April 2, 1864.

Originally heading to California along the Oregon Trail, Dr. Hunter changed his mind after hearing stories of gold strikes in Virginia City. Traveling a day behind John Bozeman’s wagon train, Dr. Andrew Jackson Hunter, his wife Susannah, and three children left North Platte along with 15 other travelers in hopes of striking it rich in the gold country of Virginia City.

On July 18, 1864, while hunting antelope a few miles north of the Yellowstone River where the small wagon train was camped, Dr. Hunter spotted the hot springs and several hundred Crow Indians that were camped there. In a memoir written by daughter Mary Hunter Doane, “My Father had spent much time at Arkansas Hot Springs, and it was his thought to return at an early date in order to secure right to these springs as a home. In January 1869, my Father with his family returned to Bozeman and again visited the Springs. In 1870 Father took the place as “Squatters’Right,” there having been no survey of that section.”

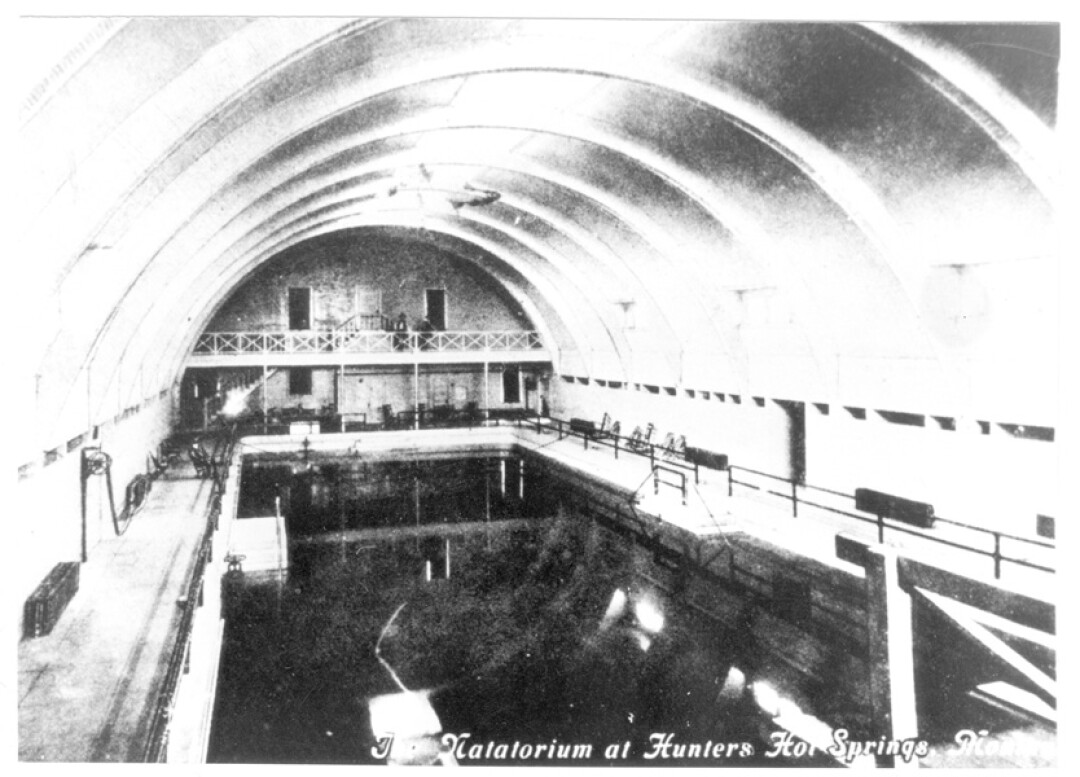

The building of a home in 1870 was closely followed by the building of a dam between the hot and cold springs. This created a pool that was used for many years by both the white visitors and the Crow people that were accustomed to frequent the place. In 1873, bath houses were constructed and work began on the sanitarium.

Until the mid-1870s, the Hunters lived at the springs intermittently due to troubles from traveling bands of Sioux and Piegan Blackfeet. In diaries, newspaper articles, and memoirs the stories of stolen horses, killed cattle, and destroyed gardens are consistent. In an article by historian Merrill Burlingame about the Hunter family and Mary Hunter Doane, he writes, “Mrs. Doane recalls many adventures which took place at the Hot Springs. During any absence of the men of the household, the house was securely barricaded, and Mrs. Hunter and the girls became adept in the use of firearms.” From The Bozeman Courier July 2, 1937, “Upon one occasion when a party of hostile Sioux was headed in their direction, Mrs. Hunter lashed children to the backs of horses and then tied herself to the back of one, and all swam the Yellowstone when it was at flood stage.”

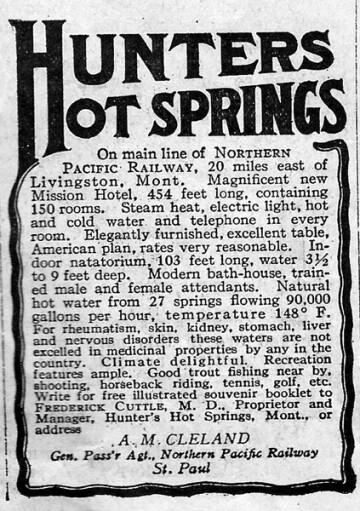

The first post office was established there in 1878, with Dr. Hunter the first postmaster. The resort got its first big boost in 1882 when the Northern Pacific Railroad pushed west through the region. By the next year Dr. Hunter had erected a hotel with full facilities.

In 1885, the hotel and development was sold to the Montana Hot Springs Company which was owned by Cyrus B. Mendenhall, Herber Roberts, and A.L. Love. Mendenhall, a rancher, put up the first frame hotel, and sought to make Hunter’s Hot Springs the county seat.

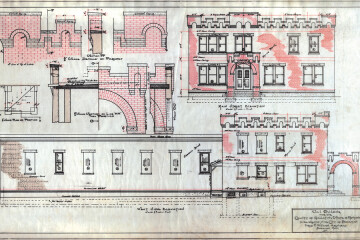

In 1889, the property was once again sold, this time to Mr. and Mrs. James A. Murray. According to the Great Falls Tribune, Murray was “a millionaire Butte banker, who was a collector of hotels and a gambler of heart.” Murray set about to build the most luxurious hotel west of St. Louis. He included the existing hotel and pool area behind the Moorish façade of the new building. Murray had the architectural firm of Link & Haire design and supervise the building project. Fred F. Willson, then working for the firm in Butte, made a number of trips to the Springs to supervise construction.

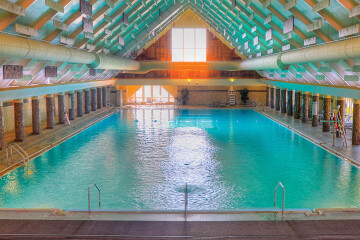

The hotel was two stories in height with a frontage of 450 feet and a depth which varied from 100 to 250 feet. The hotel could accommodate 350 guests. The semi-circular solarium on the east end of the building was enclosed with art glass windows and decorated with ferns, palms, and other plants. The pool section was reached by an enclosed corridor; the pool itself was 103 feet by 50 feet with forty dressing rooms. The Hotel Dakota was completed in 1909 at a cost of $150,000. At the same time as the hotel was being built, a bottling plant for mineral water was established.

There were five hot plunges, five vapor baths, and numerous tub baths. Outdoors there was a golf course, tennis courts, cricket fields, and saddle horses. Hunter’s Hot Springs was a major cultural center; the Montana State Republican and Democratic conventions were held at the resort. The golf course was host to several state golf tournaments, and The Montana Tennis Association held a state tennis tournament in 1909; the courts were fashioned from a mixture of sand and molasses. This sun baked surface provided a “firm resilient surface.”

Hunter’s Hot Springs had a farm that supplied fresh vegetables, a ranch that supplied beef, and a herd of dairy cows that supplied the Hotel Dakota with milk; a poultry farm provided eggs and chickens. The resort prospered, the food was superb and there was live music every evening for entertainment and dancing. In 1914, five trains each day, three westbound and two eastbound, stopped at Springdale, providing easy transportation for folks looking for a therapeutic soak, relaxing vacation, or party-filled weekend.

Time, however, brought a change in modes of transportation. At first the automobile was expected to increase the hotel business, but it had a different effect. Travelers tended to travel farther and spend less time in any given place. Then another blow fell when prohibition was enacted in Montana in 1916. Hunter’s Bar had long been one of the best known drinking establishments in the state with a well-stocked cellar of fine wines and liquors.

An article in the Great Falls Tribune stated, “Determined to continue the jovial element of good cheer, but quite out of keeping with traditional standards, the resort management entered the manufacture of liquor. In a tree-shaded hollow the officials set up a distillery and hired a man to operate it. Here, where the necessary water flowed from underground springs, they contrived to make fine bourbon…It was bottled in the old bottling plant and sold to all who came. The liquor business flourish; that of mineral water ceased.”

Bootlegging had an unfortunate effect on the reputation of the resort. By the end of the 1920s, though it was still grand, it was no longer a family place. On November 3, 1932, the Hotel Dakota burned in about four hours. The fire was caused by an electrical fault in the west wing, which was suspected and sought for days before. Ironically, the reservoir and hydrants that were needed to fight the fire had been drained on November 1st to guard against freezing.

Although the hotel was gone, the springs continued to flow and the property sold in 1944. The pool was restored and a Quonset hut erected over it. Harold and Mavis Johnson operated the pool where many area children had weekly swim lessons and attended swim meets. The Johnsons closed the pool in 1974 because of the labor involved in keeping it opened.

In 1989, the property was sold to Japanese investors who put up two greenhouses to take advantage of the thermal springs. This effort failed by the fall of 1992, citing poor economic conditions in Japan.

Today, the only thing that remains of Hunter Hot Springs is the capped springs, which are difficult to find, but can sometimes be seen at the base of a trail of steam that has escaped from the caps. To locate Hunter Hot Springs today and see if you can envision an enormous hotel on its site, take I-90 east past Livingston to exit 354 toward MT-563 Springdale.