SIlence Speaks

In and around 1987, I was playing in the house band for The Tracey Ullman Show on Fox. Tracey is one of the funniest and genuinely nicest people I have ever met in the “business of music.” The band was stellar: Richard Gibbs was our fearless leader, musical director, and keyboard player; David Chamberlin alternated with Kevin McCormick on bass; and multi-instrumentalist (don’t you hate those guys?) Joe Turano played keyboards and reeds. We had a floating guitar chair, anchored by the great Michael Now, supplemented by George Doering, Michael Thompson, Michael Levin, and Paul Jackson, Jr. My brothers in arms were remarkable, to say the least. As a musician, one of the most coveted gigs in town is live television. I was fortunate to play in the house band for the first two seasons of American Idol, as well as the short-lived “Late Night with Joan Rivers” as a sub for Vinnie Colaiuta.

Live television is usually a terrific medium for a studio musician because most of the time it requires a rehearsal at 5 o’clock or so, and then the show goes live to tape at 7:00 or 7:30pm, enabling us “studio guys” to play our recording sessions during the day and then make our way over to the soundstage for rehearsal and the show. In a way, it is a “having our cake and eating it too” scenario.

The Tracey Ullman Show was a different animal altogether. The foundational band would rehearse during the course of the week, beginning on Monday, and the rehearsal would culminate in the live taping of the show on Friday evening. It was literally a 9-to-5 kind of a gig, with no room for session work in between. We signed a contract to that effect. It was a huge commitment for us musicians, but it paid quite well, and the creative benefits were through the roof. Working with a comedian like Tracey is indeed one of the most wonderful musical pleasures of my life. I also had the unique honor of meeting some amazing people, including Paula Abdul, who was the choreographer on the show. There were guest stars galore sprinkled through the run of multiple seasons, and, of course, the cast was impeccable.

The year 1987 was a difficult time for one Michael Jochum. I was blessed with a wonderful gig and two beautiful little girls, but my mind was spinning. My mind was spun. I was living with an absolute sense of dread and foreboding. My other self was living the dream, while my true self was dying a slow, tedious death.

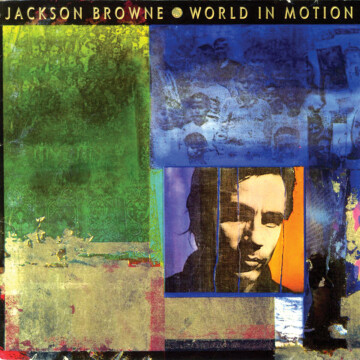

It was during this period in time when my dear friend Kevin McCormick recommended me to one Jackson Browne. Kevin had always been a huge supporter of my playing, and when he had the opportunity to recommend a drummer to flesh out Jackson’s “World in Motion” record, with touring to follow, Kevin recommended one, Michael Jochum.

Decisions, decisions. . . . Do I stay with the creative flow that was offered to me by performing in The Tracy Ullman Show band, or do I make the executive decision to meet with Mr. Browne? This was, of course, what is usually termed a “high-quality problem.” But inside, I had more, seemingly unsolvable problems. I felt dead inside. Absolutely dead. I crawled into a vicious cycle of pills and potions to try to alleviate a world that I simply could not live in.

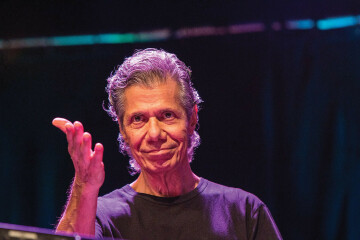

On Kevin’s recommendation, Jackson gave me the musical opportunity of a lifetime. Jackson had the utmost respect for Kevin (and well deserved, as Kevin is one of the most beautiful people I have ever met in the music business). So, on his recommendation alone, I made my way over to Jackson’s studio in Santa Monica, California, and immediately, without fanfare or audition, I began recording with one of the most remarkable bands I have ever played. Musicianship beyond compare, the talent included Bob Glaub on bass, Scott Thurston on keyboards (along with Craig Doerge), and Kevin Dukes on guitar. From the first day of recording, Jackson trusted me implicitly and listened to all my suggestions. His faith in my God-given talent fueled me, at least for a time.

I had to let go of my coveted television gig, but my creative flow was flowing mightily. I would make my way to the recording studio every day with the beautiful expectation of digging into another one of Jackson’s amazing songs. I was fueled for a time, supported by my incredible bandmates and Jackson’s intuitive nature. I would leave the studio late in the evening with that feeling of accomplishment unparalleled in the flow of making a record. Putting on tape (yes, kids, it was 1987, and we recorded to tape!) something that has such depth and weight to it is, in a word, transcendent.

My life continued in this way for the next several months of the record’s construction, and I was bolstered by the fact that the making of this record would be followed by a benefit tour, which included the likes of Bonnie Raitt and the great David Lindley. The benefit tour would then be followed by a major US tour to support the new record. When the time came for the tour, I knew that I needed to pull my shit together.

Unfortunately, thinking that I could pull my shit together was the tallest of all orders, as this time in my personal life was one of absolute chaos. I managed to pull myself through the benefit tour work fairly unscathed, but my mind continued to spin out as we put the final touches on the record and began to prepare for the national tour. My marriage was in shambles, my truest sense of Self had disappeared, and my other self was barely hanging on. It was apparent to everyone involved that I was having a difficult time. It was certainly the most apparent to one Jackson Browne, who was inquiring after each of our shows in a very gentle way, “What’s the matter with Michael? How is this Michael Jochum, who had performed so well in the studio on my most recent record, the same Michael Jochum who is seemingly unable to pull it together to perform consistently well every evening on my tour?” Jackson took me aside on several occasions and asked if there was anything he could do to help. I would of course give him one of the old, “Well I didn’t get much sleep last night,” or “I couldn’t really hear the click very well,” or “My monitor mix was pretty shitty, but I promise tonight is going to be better.” I remember using the “I’m sorry” ploy many times with Jackson, and he finally turned to me one evening after a particularly bad performance by myself and said, “Michael, please don’t say that you’re sorry anymore.”

Towards the end of the West Coast swing of our national tour, there were no more “I’m sorry”s. There was no more “I couldn’t hear myself in the monitors.” There were no more excuses. We were in Seattle, and Jackson dialed up my hotel room in the middle of the night after an especially uncomfortable show and asked to see me in his room. Making my way to his room, I felt emboldened by some particular pill or some unknown potion, but I intuitively had a deep-seated feeling of ending. And then Mr. Browne did something totally unexpected. Jackson invited me out in the middle of the night to his favorite coffee shop in downtown Seattle for a piece of pie.

As we made our way to this particular pie emporium, not a word was spoken. Words were simply unnecessary. Everything that had been said, all of my excuses and justifications were spent, like all the salt in the oceans. I knew in that moment of shared silence in Jackson’s rental car that I would be dismissed. Jackson and I bellied up to the coffee counter and ordered coffee and pie—lemon meringue for him, apple for me. Not a word was spoken as we made our way back to the hotel on that early, wet morning in Seattle. Words were unnecessary in the early morning hours. Silence speaks.